Eight in ten skilled ICT migrants end up finding “fulfilling roles” in Australia’s IT sector, according to new ACS research that also found more than half challenged by complex migration processes, workplace discrimination, visa issues, and a lack of regional IT jobs.

The first in a series of analyses that will track ICT migration outcomes, Skilled Journeys: Navigating IT Migration in Australia surveyed 2,303 ICT skilled migrants in mid-2023 – finding, among other things, that 90 per cent of skilled migrants ended up finding some form of employment in Australia, and 80 per cent were working in the IT sector.

Most were positive about their decision to migrate to Australia, and said they would recommend the move to others – suggesting that overseas campaigns marketing Australia as a migration destination would find a receptive audience.

The results of the report “run counter to the popular narrative that gig economy work is the inevitable outcome of Australia’s skilled migration system,” ACS chief growth officer Siobhan O’Sullivan said as the new report was released.

“When it comes to the IT workforce,” she continued, “the vast majority are finding fulfilling roles in the right fields.”

Skilled migrants, she said, are providing a “valuable contribution” including “helping fill the critical shortage of IT professionals in Australia, especially in a time when the tech industry is facing unprecedented demand for skilled talent.”

Regional areas had particularly benefited from skilled migration, with 27 per cent of respondents saying they lived outside of Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane – up from 18 per cent in 2017.

Yet that growth was threatened by job availability, with just 43 per cent of respondents saying they intended to stay in a regional area for more than five years, or indefinitely – a point that led ACS to recommend additional incentives for migrants and employers in regional areas, as well as promoting infrastructure and professional opportunities in regional areas.

“For many migrants, regional Australia just doesn’t have the opportunities for career progression that they want,” O’Sullivan said. “That’s something we need to address at the policy level.”

Lingering obstacles threaten sector’s growth

For all the positive experiences they shared, respondents indicated a range of lingering issues – including one quarter who felt discriminated against due to their migration status; half who said visa restrictions on work rights had “hindered” their job search; and a “sizeable minority” who took over six months to secure a job in the IT sector, or ended up working in other industries.

The problem had gotten worse over time, with 15 per cent of respondents reporting they were working outside of IT in 2022 – up from 5 per cent in 2018.

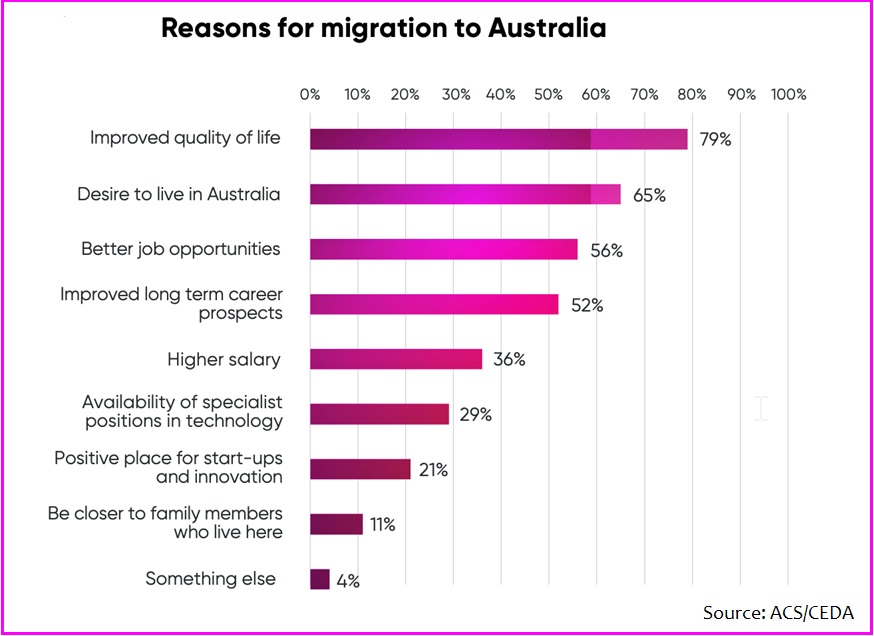

This level of underemployment is less than ideal given that 56 per cent of respondents said they had decided to migrate to Australia for better job opportunities, 52 per cent cited improved long-term career prospects in Australia, and 29 per cent attributed the decision to the availability of specialist technology roles.

Given that 56 per cent of ICT skilled migrants have bachelor’s degrees and 46 per cent have postgraduate qualifications – making them better educated than Australia’s population overall – ACS has advised the problem be addressed with targeted job placement programs and incentives for employers to hire recent migrants.

“If migrants continue to find it hard to get a job at their skill level in Australia, we will struggle to attract the best talent in technology and other sectors,” warned Melinda Cilento, chief executive of the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA), which partnered with ACS for the new report.

Previous CEDA research has suggested that wasting skilled migrants’ abilities cost Australia $1.25 billion in foregone wages between 2013 and 2018 alone.

Despite calls for Australia to boost the tech workforce from 935,000 to 1.2 million by 2030 – and ACS pushing for even higher numbers – many organisations are struggling to improve gender imbalance and find enough skilled workers to fill even well-paying tech roles.

A growing chorus of voices is calling for more proactive change to VET training, university education, skills development strategies, new forms of training, and Australian Public Service terms of engagement to streamline the skills pipeline.

The federal government – which recently rankled university heads after announcing migration changes including sharp cuts to the number of overseas university students – should, ACS advised, address systemic obstacles by focusing on “smoothing the path to permanent residency and citizenship” to make migration outcomes clearer.

The government’s Skilled Migration plan – which includes streamlined visa pathways such as the Skills in Demand visa, and simplified immigration processes overall – is a “beneficial initiative designed to bolster our economy, address critical skills shortages, and enhance our global competitiveness,” James Cook University chief digital officer Geoff Purcell said.

“These reforms are not just about filling jobs; they’re about driving innovation, supporting regional development, and ensuring our migration system is responsive to the dynamic needs of our economy.”