From old Nintendo Games to digital artworks, a team of Australian archivists is working to preserve prime works while they still exist.

Curators, computer scientists and librarians have partnered with Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT), Swinburne University of Technology, and Griffith University Art Museum.

Leading the project is Melanie Swalwell, professor of Digital Media Heritage at Swinburne, who said preserving these creations has now become a matter of urgency.

The gravity stems from unstable media operating systems that are constantly being superseded.

“What then happens is the software file that it has been made to run with often isn’t supported by a new version and then has to be updated,” Swalwell said.

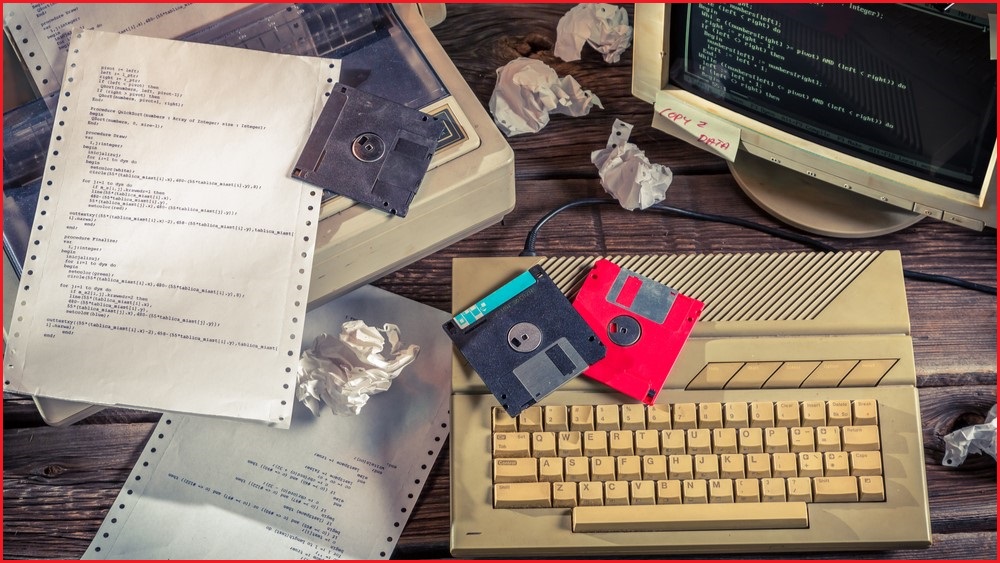

The problem is that these ‘born-digital’ artworks – art that originates in digital form, such as websites and digital photos – are on obsolete media, such as floppy disks and optical media, and rely on obsolete operating systems and hardware.

“Born-digital content has not been traditionally valued once it becomes old, sometimes it’s because it was viewed as trivial or seen as too hard to preserve.”

Components of born-digital bring special challenges:

• Magnetic computer disks suffer bit rot

• Computer hardware quickly becomes obsolete

• Software dependencies present special access challenges.

“This makes opening legacy content quite challenging, and the artists involved in this work are getting older,” Salwell said.

“We are in a race against time to save as much digital heritage as possible and write the history of the past.”

Prof Swalwell provides an example.

“If an architect wants to renovate a building, they need access to a plan. If the plans require an obsolete version of software that is no longer supported, then how are they going to do this?

“This is one of the challenges we are working to develop solutions to.”

Collecting and preserving digital content has been put in the too hard basket, Swalwell said.

“There has been a reluctance to conserve and make it accessible; many of our partner organisations didn’t know how to do this.

“So now we are in a position of having to play catchup.”

How it is preserved

Regardless of whether it is a floppy or optical disk or cartridge, a disk image is made and then that content is emulated to make this accessible.

Emulation simulates the function of obsolete systems.

“It’s not just the physical storage media that presents challenges – obsolescence of computing environments is also a significant problem.

“For instance, if a computer-aided design (CAD) file requires a particular version of AutoCAD 2000 which ran in Windows 95, then we need that to build environment by creating disk images of the utility software and the operating system,” she said.

Prof Swalwell and her team are rolling out an EaaSI (Emulation as a Service Infrastructure) network between universities and cultural institutions.

EaaSI is a shared digital infrastructure that makes it possible to share configured legacy environments across the network.

“The idea behind emulating born-digital content is to make currently inaccessible content available and accessible for our researchers.”

To date, the digital team has completed three major Australian preservation projects.

The first project preserved 50 Australian computer games from the 1980s, while the other two include 32 artworks, and 50 games from the 1990s.

“These are not just preservation projects, but history too. It’s pretty hard to go back, if you don’t have the access. We must have access to these titles if they are to be remembered.”

Play it again, Sam

Formerly known as the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, ACMI is Australia's national museum of screen culture.

Based in Melbourne and funded by the Victorian Government, the museum has been collecting and preserving video and interactive art as well as a range of video games.

In 2012, ACMI partnered in the first of several Australian Research Council-funded research projects to develop ways to document, preserve and then present historical video games made in Australia and New Zealand.

Director and CEO of ACMI, Seb Chan, said part of these research projects has been technical – how to do the preservation, and the technologies to make old software playable again.

Another aspect of this has been about documenting the stories of makers and of players.

“It’s the combination of these approaches that makes this matter. We often display playable historical video games in our exhibitions, and they are immensely popular.

“Older people reminisce about playing them as teenagers, and young people marvel at how difficult they are to play!”

With a lot of contemporary creative practice and art made using software, a vast amount of this work requires digital preservation practices.

In 2022, ACMI made some Australian video games and interactive artworks from the 1990s playable in a web browser.

Participants can experience and play some of Australia’s favourite historical video games (via emulation) in ACMI’s Story of the Moving Image Games Lab, or with EaaSI via ACMI’s website on participants laptop or mobile devices.

Chan is delighted to hear from gallery staff who relay hearing many endearing conversations between grandparents, parents, carers, and children about video games on display.

“For many people who have since grown up from the 1980s, games have been a significant part of their childhood and adolescence.

“Even for young people today, video games are a huge part of their identity and how they think about the world.”

Preservation and access

Whilst ACMI has more games and interactive art than is currently being preserved, Chan said that not all are available to play at this stage.

“Sometimes this is because the technologies for playback are not yet developed, or that the work requires specific presentation methods such as VR headsets, or multiple screens or controllers.”

Playable games are always on display for free in the Story of the Moving Image exhibition, and some titles are also playable on ACMI’s wifi network for research purposes.

You can find playable games and interactive artworks on the ACMU website.

Thirty years of preservation

In January this year, the Australian Computer Museum Society (ACMS) turned 30.

Since that time, the member-based, not-for-profit organisation has been restoring and exhibiting computers, software, artwork and more.

ACMS president and preservationist, Adrian Franulovich said with much of the foundational history of computing occurring pre-millennium, there is little to no digital records held anywhere or online.

“We need to act now to save valuable history.

“This, coupled with the founding generation disappearing fast, is causing us to lose intricate and amazing skills and knowledge of early computing and how it was able to be exploited to do amazing things with major constraints. “

He believes the digital computing revolution of the last 70 years is likely to be the most important revolution in the existence of humankind.

“If we don’t act now, we’ll be looking back in 20 or 200 or even 2000 years and wonder, how was all this digital computing done, similar to how generations today look back in wonder of how the Egyptians built pyramids!”

Franulovich is keen for others to get involved in preservation. ACMS members attend workshops to share knowledge.

“We provide workshops for members to share skills and restore both their computers and restore our equipment in a friendly environment. They’re likeminded individuals who share their knowledge and experience inter-generationally.”

He adds members have access to tools, projects and technology that they would generally only have ever dreamed about, because they are stored on the premises.

ACMS has Australia’s largest collection of “mini” computers, along with over a million sheets of documentation and thousands of disks and tapes to be imaged.

“Currently we are cataloguing, restoring and piecing together thousands of artefacts.

“Due to the sheer rarity, value and size of the items, many of the items we hold are potentially the last examples in the world.

“Our largest single computer [IBM 1401 from 1958] weighs in at 785kg for the processing unit!”

“These items can’t be housed by the general public and our organisation needs to be custodians of the hardware, software, periphery, and stories to educate new and future generations before it’s too late.”