M*A*S*H actor and now science communicator Alan Alda believes the general public could learn a lot by thinking more like scientists.

For the best part of the past two decades, Alda has focused his time off-stage and screen helping scientists “present their work to the public with clarity and in a vivid way”.

The vehicle for this exercise is the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, and it has recently struck its first international partnership with the Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science, which is based at ANU in Canberra.

It’s one of the reasons Alda is presently in Australia. Another reason he’s here is that he’s taking part in the World Science Festival Brisbane, which runs March 9-13.

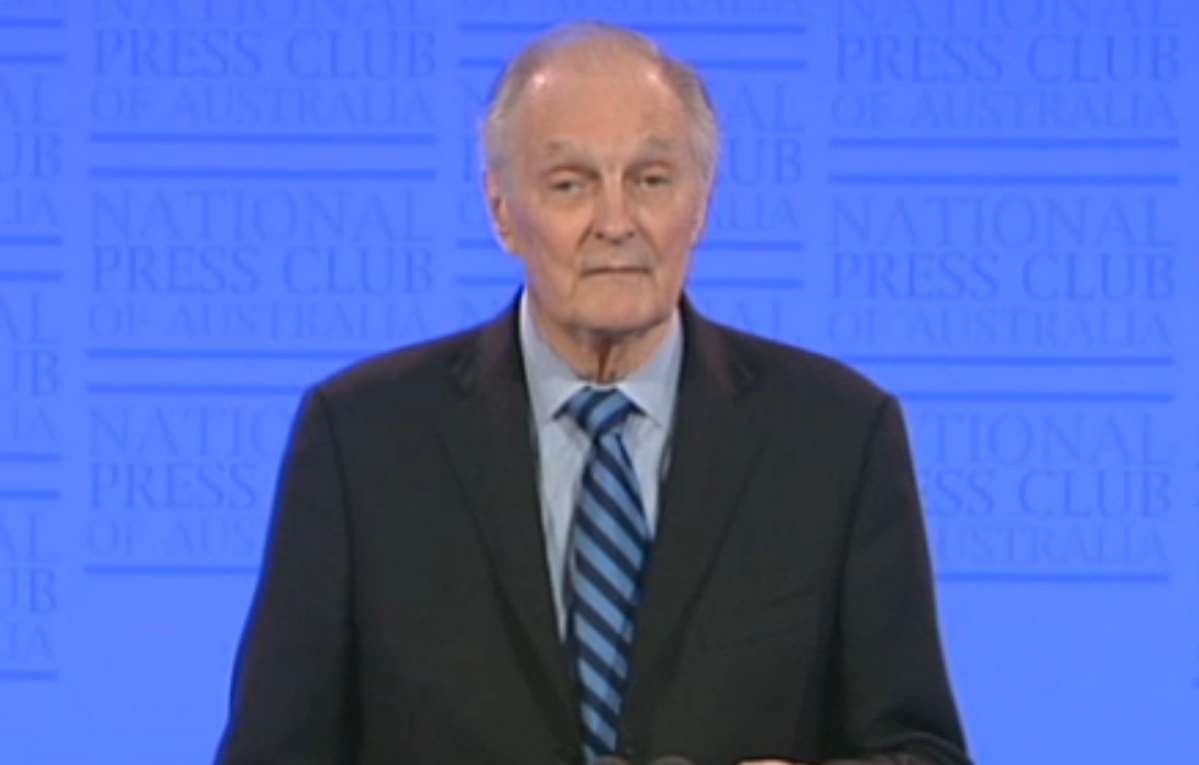

Speaking at the National Press Club, Alda said he thought the public should take the opportunity “to learn how to think like scientists.”

In particular he believed people in all walks of life could benefit from making decisions based on evidence and questioning hypotheses put before them – effectively becoming “accustomed to turning on their own ideas”.

“Science has so much to offer us in the way we make decisions and the way we think,” Alda said.

However, a major stumbling block to this occurring is that science is not currently “a daily part of our lives”, whereas he thought it should be.

“I really feel that science belongs to all of us and we all don’t have access to it the way we should,” Alda said.

“Science ought to be available and [as] refreshing as the air we breathe but it isn’t because science and the public understanding of science have drifted apart.”

One reason Alda took a more active role in science communication is because he didn’t want to leave that communication “to chance”.

“We need to hear from scientists because if we don’t hear from scientists about their own work, we’re going to hear from other people telling us about science,” he said.

Those other people could include science journalists – whom Alda had no problem with.

“But we’re also going to hear about it from people who are simply mistaken and we’ll hear about it from some people who know they’re making mistakes and who are deliberately distorting the science for their own agenda and gain,” he said.

“Unless scientists are in there telling us what the real story is we’re liable not to get the real story. That’s not going to be in our interest.”

Apart from stemming the tide of science misinformation, there were other good reasons to focus attention on how science is communicated, Alda said.

He said senior scientists that underwent programs at his centre had told him that the communication skills “helps them do their work because they’re more focused on what they’re doing.”

“That’s a result we didn’t expect,” Alda said, noting that his expectations were more around aiding the public’s and policy makers’ understanding of science.

The latter is particularly important because it is often the source of scientific research funding. “Why would they give money to anything they don’t understand? We have to be clear to them about what the science is,” he said.

Another unexpected benefit of teaching scientists to communicate better is that it aids collaboration, allowing people from different scientific disciplines to break down jargon and understand each other.

“Specialisation has made us drill down into our own understanding to such a point that we do have a separate language,” Alda said.

“I’ve been told by mathematicians that they often don’t understand one another. This shouldn’t be.

“We’re going to make more progress if we understand one another.”