Weeks after its years-long patent dispute with Oracle was revived and decided, Google faces Australian Consumer and Competition Commission (ACCC) scrutiny – and potential violations of the EU’s new general data protection regulation (GDPR) – after revelations that Android mobiles continually track and report users’ location even when they’re not supposed to.

Engineers from Oracle briefed ACCC chairman Rod Sims about their work in intercepting, analysing and decrypting messages sent by Android phones back to Google, according to reports.

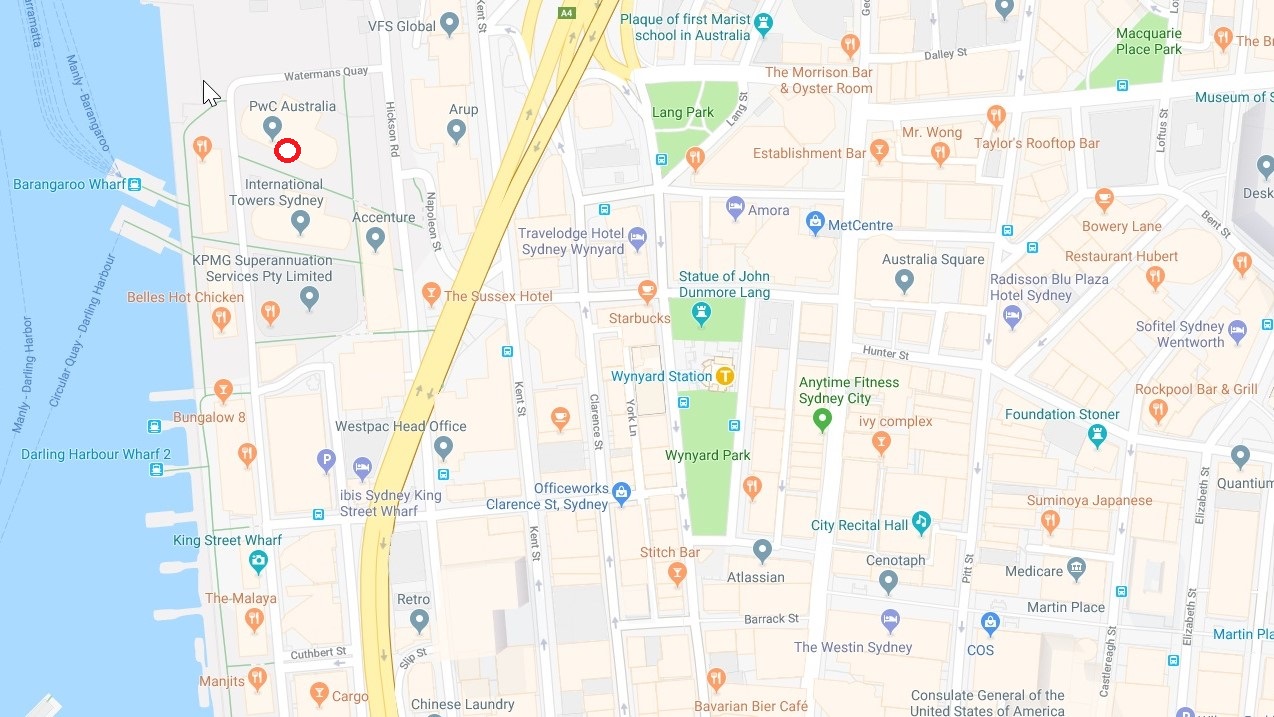

One demonstrated data analysis claimed to have identified 121 reported locations, 130 reported activities, and 354 unique WiFi base stations within a 21-minute period.

Google is known to collect location information to support location-based services such as its live traffic reporting, restaurant and business searches, advertising, and more.

But the depth and continual reporting of this data set – which included barometric readings that Oracle alleged could be used to detect which level of a shopping centre the user was on – set off alarm bells, particularly since the Android devices are reportedly transmitting the information even if users have turned off location services or removed their SIM card.

The ACCC’s investigation made worldwide news in a year where tech giants are increasingly being queried over institutionalised mass collection, reporting and sale of personal information – and using it to develop services that are a little too real.

Facebook, in particular, has been pilloried for its failure to protect consumer data from overreach by now-defunct analytics firm Cambridge Analytica.

There are also concerns about claims that the collected data is consuming up to 1GB of mobile data per month.

Some of this data may have been transmitted over home or work Wi-Fi, but many were concerned that Google was commandeering users’ monthly broadband allowances.

The average Australian mobile subscriber downloads around 2.5GB per month, according to the ABS.

Yet with strict GDPR legislation coming into effect this week – and many companies still far from ready for it – the stakes could be even higher for Google.

Collecting personal information without subscribers’ explicit opt-in could potentially violate the GDPR – which considers location data to be fundamental to ‘profiling’, lays out strict conditions for consent and requires that data subjects “be informed of the existence of profiling and the consequences of such profiling”.

It could also fall outside of Australian privacy laws that are based around Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) – which, as the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner explained in its recent GDPR guidance for Australian companies, require organisations “that collect personal information, must take reasonable steps to give individuals notice about certain matters set out in APP 5”.

Reports about the practices first surfaced in November, with Google confirming the practice and Oracle soon outed as the source of the allegations.

That turned heads, given that Oracle and Google have been embroiled in a bitter legal battle – which Oracle won just weeks ago – over Android’s use of Oracle’s Java development language.

Oracle’s further investigations, which quantified the Google data for the first time, revived the story and gave it Australian context.

Google has long argued that it gives users control over the collection and use of their data, with on-phone and online settings allowing for control over data collection.

In the lead-up to GDPR, the company explained in a blog earlier this month, it has revised its Privacy Policy, improved user controls, improved tools to help users access personal data, and will improve visibility of privacy-related settings.

“Google works to build user trust through a longstanding and strong commitment to protect privacy, and provide users with transparency and controls over the collection and use of their information in its services,” the company wrote in its April submission to the ACCC Digital Platforms Enquiry.