Known domestic violence perpetrators were among the users of a remote access Trojan (RAT) that is no longer operating thanks to a multinational law-enforcement effort spearheaded by the Australian Federal Police (AFP).

First designed as a legitimate tool for remotely administering computers the Imminent Monitor - Remote Action Trojan (IM-RAT) came into authorities’ sights after the tool was cracked and built into easy-to-use malware that allowed a user to quietly monitor, record, and control activities on a victim’s computer.

IM-RAT – which was sold via hacking websites for as little as $US25 ($A37) – has been available since 2012 and has, according to one Palo Alto Networks analysis, been used in over 115,000 attacks against the company’s customers alone.

In 2017, that security giant’s Unit 42 research arm tipped off the AFP – which brought in comparable agencies in Belgium, New Zealand, the Netherlands, the UK, and US – in an extensive investigation that has culminated in the shutdown of the RAT.

The more than two-year ‘Operation Cepheus’ saw 13 people arrested – none in Australia – as well as 85 warrants executed and 434 laptops, phones, servers and other devices seized.

The website of the RAT’s creator, Imminent Methods, now displays a splash page heralding the operation’s success.

The tool had been distributed and used by more than 14,500 buyers in 124 countries, the AFP said – including by domestic violence perpetrators who were using it as ‘stalkerware’ to spy on their targets, tracking their locations and communications, and even watch them through the computer’s webcam.

This application for RATs has often linked them with family violence, although hackers use the malware to collect all kinds of information including banking, identity, personal movements, and other details.

Although “not all uses of IM-RAT are illegal” and owning a license to the software is not illegal, AFP acting commander for cybercrime operations Chris Goldsmid said, “the offences enabled by IM-RAT are often a precursor to more insidious forms of data theft and victim manipulation, which can have far reaching privacy and safety consequences for those affected.”

“These are real crimes with real victims.”

Smelling a RAT

Because of their broad utility in applications such as stalking, surveillance, stealing financial and identity information, remote access Trojans – including the IM-RAT, the Chinese-built Derusbi, and the high-volume FlawedAmmyy – have long been a mainstay of the malware world.

As happened with IM-RAT, hackers often crack legitimate remote-support tools and create malicious derivative versions: FlawedAmmyy, for one, was based on the commercially available AmmyyAdmin remote administration tool.

Even market-leading tools like GoToMyPC and TeamViewer, which has over 200 million users globally, have been successfully compromised.

The pernicious nature of the RATs has fuelled law-enforcement activities that have been occasionally successful: in 2015, for example, Swedish malware author Alex Yücel was sentenced to 57 months in prison for writing and distributing ‘Blackshades’ malware to thousands of customers in over 100 countries.

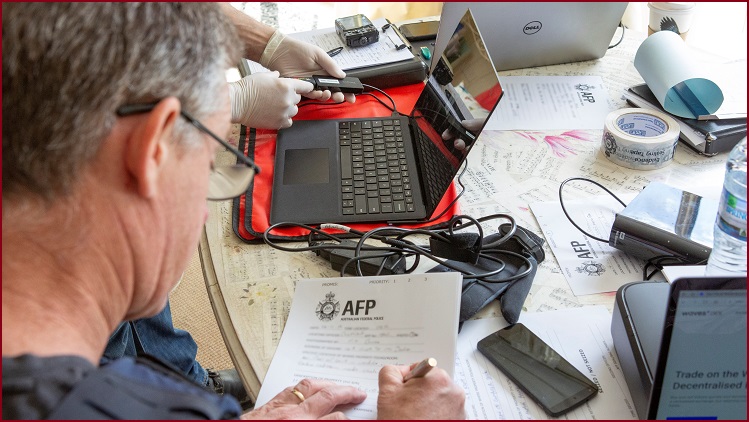

The AFP raided a home in Adelaide as part of the operation. Photo: AFP

International partnerships have, according to Goldsmid, proven crucial in executing broad-based enforcement activity necessary to take down cybercriminal operations with global reach.

“These partnerships are critical to law enforcement being able to respond to rapidly-evolving and increasingly global crime types,” he said. “We are proud to work with our international counterparts to help prevent people falling victim to spyware.”

Authorities have their hands full as new RATs emerge all the time: this week, just as the IM-RAT takedown became public, BlackBerry Cylance announced that it had discovered a new RAT, christened PyXie, that has been observed trying to deliver ransomware into healthcare and education targets.

The AFP offers guidance about RATs and advice for people who suspect they may be infected – and constant vigilance is essential.

“We now live in a world where,” European Cybercrime Centre head Steven Wilson said, “for just US$25, a cybercriminal halfway across the world can, with just a click of the mouse, access your personal details or photographs of loved ones or even spy on you.”