What does it take to build a world-class soccer-playing humanoid robot?

That's what the international RoboCup Federation aimed to find out at the RoboCup 2019 tournament in Sydney – a week-long competition testing the mettle of roboticists from around the world.

RoboCup began in 1997 as Robot World Cup Soccer with an ambitious goal:

“By the middle of the 21st century, a team of fully autonomous humanoid robot soccer players shall win a soccer game, complying witwh the official rules of FIFA, against the winner of the most recent World Cup,” said the opening statement of the RoboCup.

Considering how each adult sized robot is still closely shadowed by an exasperated handler to sure the machine doesn’t crash to the ground while kicking the ball, that goal is still a long way off.

But according to Claude Sammut, Professor of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of New South Wales and Chair of RoboCup 2019, the applications of RoboCup extend far beyond the soccer pitch.

“Often when people see the soccer robots they think it’s fun to look at but don’t realise that all the underlying technology translates to other things,” he said.

“A lot of our recent graduates have gone on to work in companies developing self-driving cars and that’s because a lot of what they’ve learned from RoboCup translates directly into those practical roles.”

Each of the five different soccer leagues represents a different technical challenge.

One league is for simulations, while two of the leagues are for humanoid robots – one that involves programming the NAO robot, and the other has competitors building their own soccer players in one of three sizes: kid, teen, or adult.

Round, wheeled robots feature in the other two leagues. Much more agile than their humanoid counterparts, these robots showcase the tactical elements of RoboCup.

No matter the league, RoboCup stretches the abilities of its competitors to the limit.

“With the NAO robot the processor onboard is probably no more powerful than your mobile phone,” Sammut said.

“So already there’s a challenge as a software engineer as to how you fit all this AI, and the software, and everything else onto a lightweight platform.

“That’s a skill that those students will go out and use everywhere.”

Walking around the massive exhibition hall at the International Convention Centre, you see long tables loaded with laptops, spare parts, energy drinks, and tired engineers.

But at the end of the day, using computer science to animate plastic and metal has its own reward – and that’s what keeps Sammut coming back year after year.

“Our team won in 2014 and 2015 because we probably had the best walk,” Sammut said.

“Walking is very much a software problem because you have to things like control how quickly and how high you move the legs. So we had the best walk and were most agile on the pitch those years.

“But because it’s not just a competition, it’s a scientific event, and we’re trying to improve the technology, we published what we did.

“In that sense we kind of threw away our advantage but the point is to exchange ideas and get better every year.”

Real-world scenarios

More than 20 years on from its inception, RoboCup features a variety of other competitions that help progress the field of robotics and have obvious real-world applications.

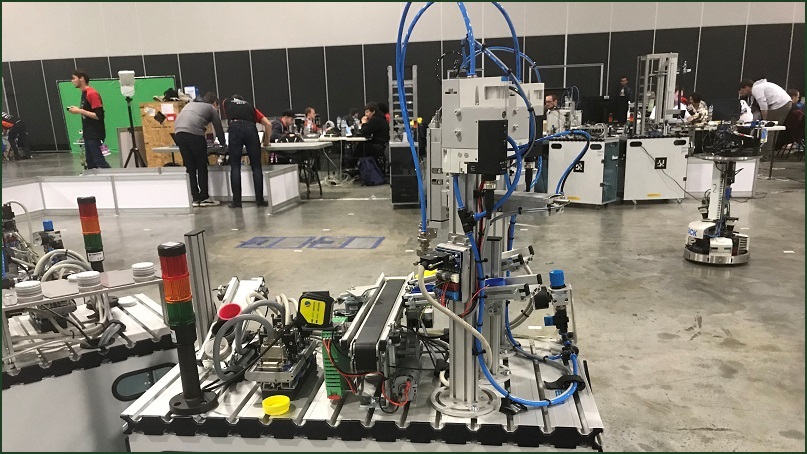

The Industrial league features an event that sees teams developing miniature factory with another robot that can adjust the machinery on the fly, making them more flexible.

In the Rescue league, robots are rigorously tested for their ability to traverse difficult terrain and interact with the environment using pincers.

Developed using a set of US standards, the trial course was dismantled after RoboCup and will be used by the NSW Rescue and Bomb Disposal Unit to train their robot operators.

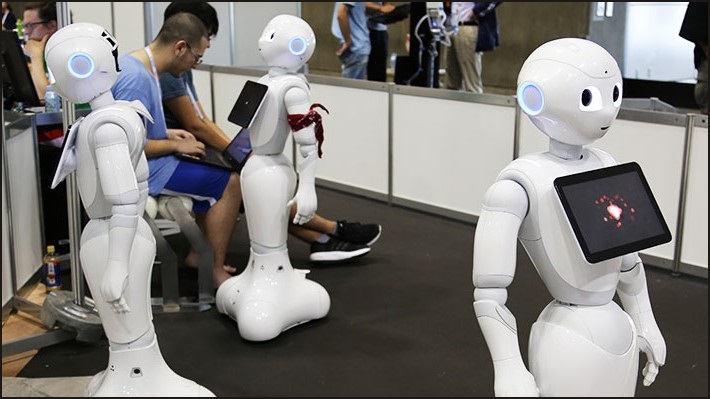

While those robots are designed to used by specialists in extreme circumstances, the ones competing in the @Home league had functions with obvious commercial implications.

Here the robots were tested on their ability to communicate with and track people, as well as identifying and picking up household objects.

In the ‘Find My Mates’ event, the robot speaks with its handler and is given a name. Then, the robot has to enter another room, find the guest, and tell its operator where the guest was sitting and what they looked like.

Another event had robots performing domestic tasks like tidying up table tops.

ACS was the STEM Champion for RoboCup 2019.