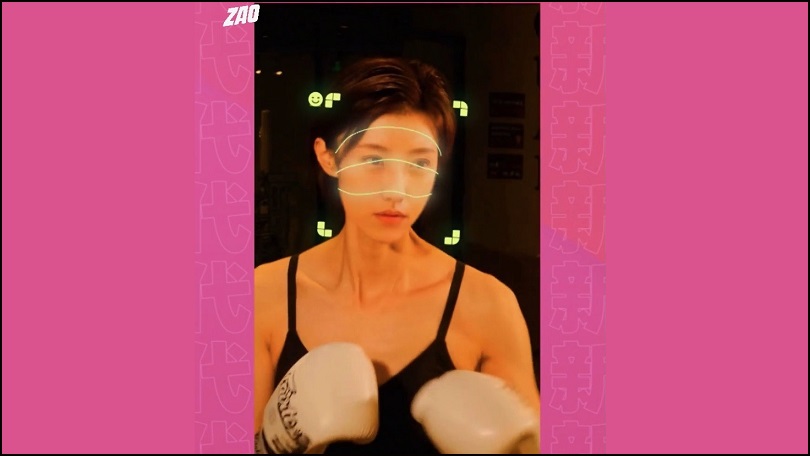

An app that seamlessly puts your face on top of actors faces in popular movies and TV shows has gone viral in China.

One photo is all it takes to swap Leonardo Di Caprio’s face for your own.

Zao shot immediately to the top of the App Store charts. Its developers said they burnt through one third of their $6.5 million a month data server.

Use of the app requires SMS verification to a Chinese phone number which makes it largely inaccessible to international audiences.

As with storm that surrounded selfie-ageing FaceApp in July, controversy followed hot on the heels of Zao’s rising popularity.

WeChat blocked the native sharing of Zao links to its platform.

I am in absolute awe of #ZAO. I uploaded a couple selfies, choose a clip, and seriously in less then 30 seconds had myself fully deep faked in. I can't wait till I can watch entire films where every character is me.

— Nikk Mitchell 🛸 (@nikkmitchell) September 2, 2019

On a side note to the developers, please don't be evil. pic.twitter.com/Y7qCpghfw9

Users raised concerns about how the facial images were used and stored – a problem especially relevant in China where you can pay for things by just scanning your face.

But Zao promptly responded on China’s Twitter-like social media platform, Weibo, saying they were reviewing the app’s privacy policy.

“We understand your concerns about privacy and security issues very much, and we also value your feedback, opinions and suggestions,” the Zao statement said.

“We will thoroughly sort out the text of the terms of the user agreement in order to modify and adjust the areas that cause ambiguity and concern.”

Zao said it did not store biometric facial information, and that the type of data used in the app could not be used to mimic facial payment systems.

The rise of deep fakes

Zao – as a quick, easy-to-use mobile app – proves just how far deep fake technology has come.

Joining in the discussion on Twitter, some users hinted at possible uses for quick face-mapping technology.

Advertisers, for example, could use deep fakes to directly copy your face into targeted ads, and movies could charge a little more to make you the star of the show.

There also remains an undercurrent of concern that the ease of deep fakes, as shown with Zao, will make it more difficult to trust the veracity of news videos.

Roger Taylor, chair of the UK’s Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation, said at an AI ethics seminar in Sydney last week that deep fakes have not come up as an immediate cause for concern.

“And one of the reasons for thinking that is because, when you look at the rate and technology used to lie online, deep fakes is useful but it’s not like it’s massively enhancing people’s ability to tell complete fibs online.

“The way it works already is people take a video of a missile hitting a region and write underneath that it happened somewhere where it didn’t happen and how many people were killed.

“You don’t need any deep fake technology to do that.”

‘Fake news’ was the Collins Dictionary word of the year for 2017.

Since then we have seen the deliberate spread of misinformation become a global talking point.

“There is a real problem with misinformation online,” Taylor said.

“The improvement in the tech to enable people to lie is certainly an issue, but the main issue is the technology that allows the dissemination and spread of false information at a very high rate.

“That’s what I worry about more.”

Matt Aldridge from cyber security firm Webroot said Zao was another step for extremely dangerous deep fake technology.

“A future of widespread distrust is coming,” he said.

“We may think that we’re having a video call with a close colleague or a loved one, but the other party is actually an imposter.

“We need to start preparing for this now and understand how we can ensure that our communications are all real and secure.”