What happens when the group behind one of the world’s most rampant ransomware campaign goes offline?

You wait for their return.

Back in May, the GandCrab ransomware gang decided to call it quits, leaving cybersecurity researchers scratching their heads.

At the recent MPower conference in Las Vegas, Raj Samani, special advisor to the European Cybercrime Centre and Chief Scientist with cybersecurity firm McAfee, told journalists how experts quickly found proof of the GandCrab crew returning.

“We were told that the GandCrab ransomware group retired because they had made over two billion dollars and went to go live on a beach somewhere,” he said.

“Now we have evidence that the best performing infectors of GandCrab have moved on to using Sodinokibi – the most prevalent form of ransomware out today.

“This is brand new, only a few months old, but it is already causing damage.”

Ransomware remains one of the simplest and most damaging forms of malware. As single phishing email can be all it takes for an organisation’s whole computer system to be locked down, encrypted until the victim coughs up the ransom money.

Just last week a targeted ransomware attack severely disrupted hospital systems in regional Victoria.

And over the past six months, similar attacks have wreaked havoc on municipalities throughout the United States – leading to an IT department head losing his job.

“In 2014, ransomware was all about sending emails to random consumers, but today’s news stories are about hospitals closing their doors because of this malware,” Samani said.

“It’s impacting cities, government entities, and businesses all across the world.”

Samani works closely with the No More Ransom group that provides free decryption tools for victims of ransomware – a service that causes their malicious antagonists to constantly adjust their own products.

When examining samples of the new Sodinokibi threat, Samani’s research team discovered that its developers nested ID numbers within the software in order to track the work of each ransomware infector.

“What the criminals have done, which is really quite business oriented, is create an accounting model to understand which of the affiliates are making the infections and which are successful,” Samani said.

“Developers make and update the malware but they’re not the individuals who send out the attacks. Instead, they go and hire affiliates. This is a business model that affords them ability to remain at arms-length when infecting organisations.”

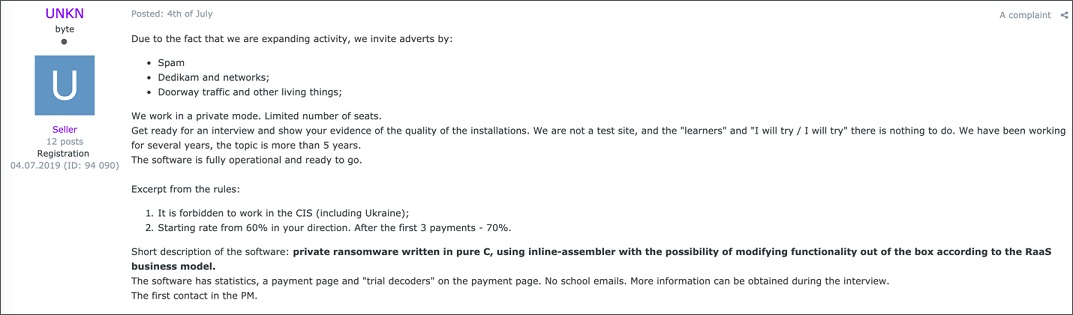

A forum user recruiting for the latest ransomware. Source: McAfee

By helping to understand the economics at play, Samani hopes to provide more help to law enforcement in fighting the shadow economy underpinning these attacks.

“This is a business model they’ve created and it is very successful," Samani said.

“The importance of this research is that, across most reporting we see the question ‘Who’s behind the infections?’, but still no one quite understands the sophisticated business model of affiliates and sub-affiliates that underpins these campaigns.

“We don’t know exactly who is behind this.

“They’re not going after Russian and [former Soviet Union] countries and the common belief is to attribute attacks to countries in this region.

“What we know is that ransomware is no longer an issue that only consumers need to worry about.

“Affiliates of these developers can infect environments by manual hacking and then lay dormant until they understand the system. Then they’ll encrypt the major systems that are required for that business to operate.

“And we have seen that holding whole cities hostage is not just plausible, it’s possible.”

Casey Tonkin travelled to the McAfee MPower conference in Las Vegas as a guest of McAfee.