Creators of online children’s content could be forced to cut jobs as new YouTube content-rating policies threaten to dry up the advertising revenue streams on which they depend.

The new policy, which was outlined in a YouTube blog and came into effect on 6 January, forces creators of YouTube content to explicitly label their videos as being made for kids or not.

Advertisers will be blocked from collecting information viewers of such videos, with content creators prevented from targeted advertising to under-13s.

The changes are intended to bring YouTube into compliance with the United States’ 20-year-old Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) rule, which prevents online operators from collecting data from users under 13 without verifiable parental consent.

Because it used persistent advertising identifiers to track the viewing habits of those watching child-focused videos, YouTube parent company Google was accused of earning “millions of dollars” for violating COPPA in a FTC lawsuit that led to a $243m ($US170m) settlement (watch the announcement here) last September.

Terms of that settlement included the enforcement of child-only content restrictions, which became mandatory this month.

The changes will be rolled out globally this year, with YouTube producers in Australia and other non-US jurisdictions pressed to consider whether their country’s definition of ‘kid’ also implies a cut-off age of 13.

Putting a price on privacy

Child-advocacy groups have been complaining about YouTube’s behaviour for years, arguing in a formal submission that YouTube only paid lip service to COPPA with terms of service requiring users to be at least 13 and an alternative YouTube Kids app designed for younger users.

YouTube has long maintained that the rules mean its service isn’t for kids – but some 19 individual groups fought back hard in comments to the FTC after Google pushed for an exemption based on the argument that many adults watch kids’ videos as well.

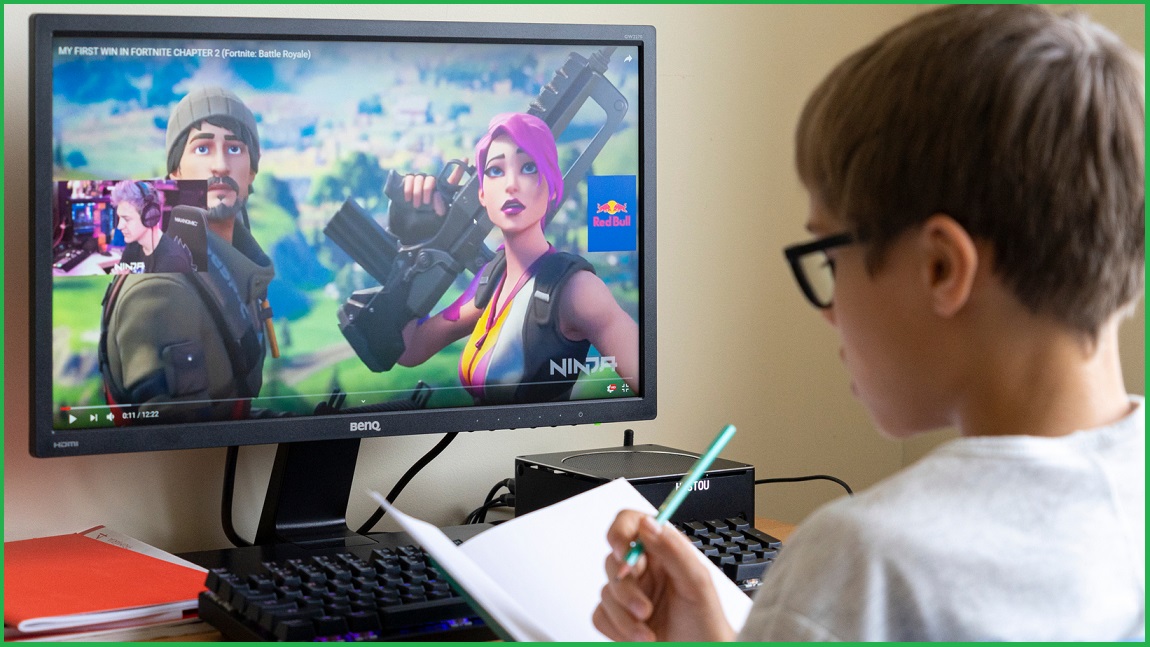

Content producers are lamenting the end of the “golden age of kids’ YouTube” and critics are wondering how the “hellscape of kids’ videos” ever got to become such big business.

COPPA doesn’t have a direct analogue in Australia but the global nature of YouTube’s policy means the effects are likely to be felt here – particularly given the mass movement of children’s viewing from TV to online platforms.

The extent of that change in viewing habits became clear in a recent government review, which cited OzTAM figures suggesting that audiences for pre-school TV programming dropped by two-thirds from 2010 to 2016 and 5-to-13 audiences dropped by half.

That review recommended the abolition of quotas on children’s programming “that is not reaching its intended audience”, freeing free-to-air networks from the “massive commitment of resources” that was no longer meetings its intended goals.

Setting the new rules for children’s content

With some 15 million Australians using YouTube every month, there is little question about where the rest of the country’s children are going for their kids videos – and YouTube knows it, having invested $143m (US$100m) in a fund to support original children’s content.

With advertisers now effectively blocked from targeting the demographic, the impact on advertisers – and, by extension, content creators – could be significant.

Communications Council general manager Prue Tehan told Information Age that the local industry has been keeping a watching brief on the latest “important” developments.

“We fully support the current legislative and regulatory system, and understand and welcome measures designed to bring the digital platforms under its control,” she said.

“We also support measures to ensure advertisers are responsible in the content they share, particularly towards children and vulnerable members of society.”

A recent TechFreedom panel discussion on the topic surfaced concerns about the new policy, with one viewer noting the “incredibly complex” COPPA environment and warning that “the people making the law have no idea what the consequences of their changes are going to be.”

Video producers worry the regulations could destroy careers: for example, YouTube success story Bounce Patrol – whose repertoire includes a colour-drenched version (with 1.1 billion views) of the Baby Shark sensation (which itself has over 4.3 billion views) – expects excluding its videos from the advertising ecosystem will slash revenues by 90 per cent.

Just what constitutes being ‘made for kids’ is highly subjective, but YouTube and the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC), among others, offer guidelines that include factors such as subject matter; the use of child actors; whether the video uses child-specific language or features characters, celebrities, or toys that appeal to children; and more.