Whether or not real-world benchmarks meet the hype of its latest launch, Apple’s release of laptop and desktop systems based on its M1 system-on-a-chip (SoC) marks the beginning of a major architectural change that will, among other things, run iPhone and iPad apps on desktop computers for the first time.

The announcement of Apple’s M1 chip – which was promoted using the ‘One more thing’ catchphrase reserved for the company’s biggest products – came via a virtual Apple event where CEO Tim Cook was joined by the company’s technical heads to explain why the company would stop using industry-standard Intel processors.

Years of building Bionic processors for its iPhones and iPads had helped the company refine its chipmaking strategy to the point where it could transition desktop Macs to what Apple senior vice president of hardware technologies Johny Srouji called a “stunningly capable chip”.

The M1 combines an 8-core CPU, 8-core graphics processing unit, and 16-core ‘Neural Engine’ designed to churn through the machine learning (ML) algorithms that power artificial-intelligence applications.

Each of these capabilities – as well as security, communications and media-processing capabilities – used to be provided by different chips, but Apple’s SoC design lets the features work together much more smoothly.

Apple’s decision to break the M1 into two groups of four cores – four power-hungry high-performance cores for complex applications and four high-efficiency cores for everyday computing tasks – reduces power consumption dramatically.

The four high-efficiency cores together run about as quickly as Apple’s current MacBook Air, Apple said, while consuming less power and generating less heat.

Power consumption is so low that Apple claims an 18-hour battery life for its entry-level MacBook Air and 20 hours for its high-end MacBook Pro models.

The road never taken

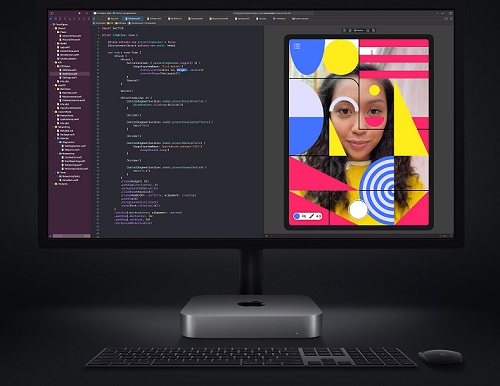

Even as hardware experts chomp at the bit for benchmarking opportunities, the new architecture also powers an updated desktop Mac Mini that will kick off a two-year refresh of Apple’s product line.

Apple has partnered with Taiwanese manufacturer TSMC – which will open a $17b ($US12b) plant in Arizona by 2024 – to build its M1 using a 5-nanometre CPU manufacturing process.

The 5nm manufacturing process enables much higher computational density than the 10nm process used by Intel – which won’t adopt 7nm manufacturing until at least 2022.

The new Apple Mac Mini. Photo: Apple

With 16 billion transistors on the M1 chip, Srouji said, the company has been able to tweak each element “to make each of these technologies best in class…. We’ve been advancing it year after year.”

The hardware is just part of the company’s new direction, which has been evolving ever since Apple announced in 2018 that it would move to a completely 64-bit architecture – and revealed this June that it would release its own chip before year’s end.

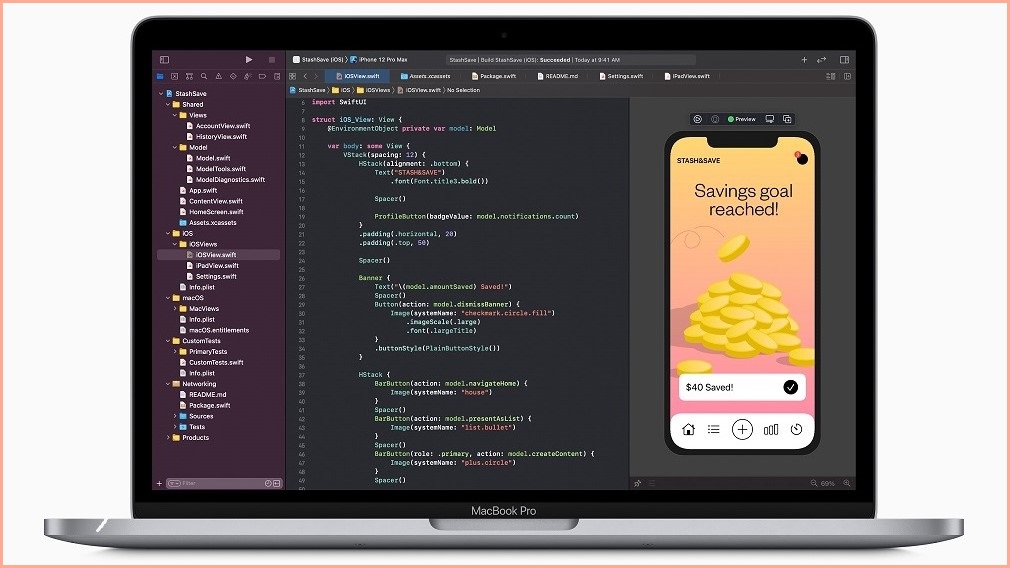

The chip is about more than just speed, however: by transitioning to an Arm-based architecture like that used in its iPhone and iPad, Apple has been able to design its new Big Sur operating system so that it runs existing Mac applications and iOS applications, side by side.

This would have been impossible using processors from Intel, to which Apple switched in 2006 after its previous PowerPC chips failed to keep up with Intel’s pace of innovation.

With the tables now turned, Apple will leverage its new architecture to blur the boundaries between desktop and mobile devices, making it easier for software developers to build one app that runs on any Apple product – and to build mobile apps that can take advantage of the M1 chip’s features.

It’s not the first time mobile apps have been extended onto the desktop – third-party Android emulators have been around for some time while a recently released feature of Microsoft Windows 10 lets users run Android apps on the desktop from Samsung Galaxy phones – but Apple believes its explicit support will hasten the convergence of desktop and mobile worlds.

“The Mac has never had a chip upgrade this profound,” Srouji said, “but the silicon is only part of the story… it’s the tight integration of our hardware and software that makes the user experience.”