Google’s location data shows that, yes, we are indeed spending less time out of the house thanks to the coronavirus pandemic.

The unsurprising results come from the tech giant’s first ‘community mobility reports’ that are designed to quantify and illustrate the effects of pandemic policies around the world.

A blog post from Senior VP of Google Geo, Jen Fitzpatrick, and Google’s Chief Health Officer, Karen DeSalvo, explained how the data could be useful for information public health decisions.

“For example, this information could help officials understand changes in essential trips that can shape recommendations on business hours or inform delivery service offerings,” the post said.

“Similarly, persistent visits to transportation hubs might indicate the need to add additional buses or trains in order to allow people who need to travel room to spread out for social distancing.

“Ultimately, understanding not only whether people are travelling, but also trends in destinations, can help officials design guidance to protect public health and essential needs of communities.”

Australia, Google is watching

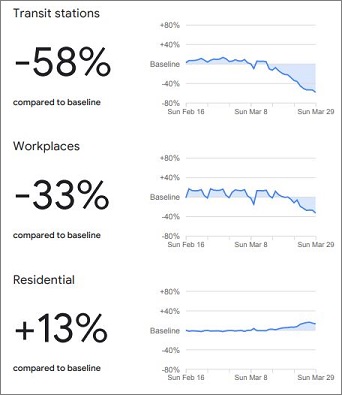

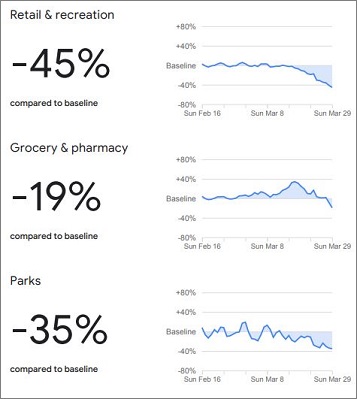

Measured across four location categories – retail and recreation, grocery and pharmacy, parks, transit stations, workplaces, and residential – the report data seems to confirm the intent of Australia’s, at times confusing, social distancing policies.

Australians are spending more time at home. From 16 February 16 to 29 March – a week after nation-wide social distancing measures were put in place – we were at home 13 per cent more often than usual.

Transit stations – like bus stops and train stations – saw a reduction of nearly 60 per cent, while retail and recreation locations such as restaurants, shopping centres, and libraries have seen a 45 per cent reduction over the same period.

Visits to grocery stores and pharmacies were down, but not by as much as other location types like parks (which includes beaches) where police have enforced social distancing rules.

The changes in behaviour are compared with a baseline median value derived from data gathered between 3 January and 6 February.

The creepy line

Google’s reports venture close to what former Google CEO Eric Schmidt once called the ‘creepy line’ – an imaginary limit to the company’s surveillance powers that he said Google’s policy was to “get right up to … and not cross”.

Location data is supposedly anonymised – a process that is exceedingly difficult to do properly – with Fitzpatrick and DeSalvo reiterating that “no personally identifiable information, like an individual’s location, contacts or movement, is made available at any point”.

Only users who have opted into the Location History setting on their Google accounts will have data used for this purpose, though Google said it will not public reveal specific the number of users as part of its reports.

Google isn’t alone with its decision to provide its extremely valuable data for the purpose of public health.

Reuters reported last week that Facebook is providing mobile location data to infectious disease researchers in the US.

Mobile location data isn’t infallible, however, as was proven when German artist Simon Weckert used 99 smart phones to create a virtual traffic jam on Google Maps in back in February.