Australia’s competition and consumer regulator may be talking tough about the “dreadful cartel” keeping petrol prices high, but it admits it can do little more than watch as online merchants rip off consumers desperate to protect themselves against the expanding coronavirus pandemic.

eBay and Facebook “are allowing parasites to flog off things like toilet paper at ridiculously inflated prices,” Agriculture Minister David Littleproud said in recently calling out marked increases in prices on hard-to-find personal healthcare items like protective masks, hand sanitiser and toilet paper.

Price gouging “is a low act”, Littleproud said, warning that the online giants “have a duty to act ethically” and “will be aiding the exploitation of anxious people during these challenging times” if they fail to rein in surging prices.

Consumer-advocacy group CHOICE flagged “rampant” price gouging, pleading with vendors to stop the “deeply unethical and downright nasty” practice – and “let their conscience be their guides and stop flogging overpriced goods”.

CHOICE said it had been fielding reports of face masks being sold for 10 to 20 times their normal price, hand sanitiser doubling, and the price of many staple foods surging.

Even large chest freezers – normally a discretionary purchase for milk bars and heavy consumers of meat and ice cream – had more than quadrupled in price.

Exploiting the public’s fears

A casual search of eBay by Information Age confirmed that price gouging remains both common and extreme.

Bulk packs of toilet paper normally cost less than $0.50 per roll, but online listings showed it variously selling for $5 per roll, $4.40 per roll, and $2 per roll.

P2 and N95 masks, widely sought after for coronavirus protection, used to cost less than $1.50 each at Bunnings but eBay merchants were charging $15.95, $12.80, and $12. One medical supplier lists a box of 30 N95 masks for $1072.50 – equal to $36 each.

Hand sanitiser, which can normally be found for $14.49 for a 1L bottle, was selling on eBay for $49.95 for half as much. And 50mL bottles – normally a $2.99 purchase – selling online for $45.95, $37.50, and $29.99.

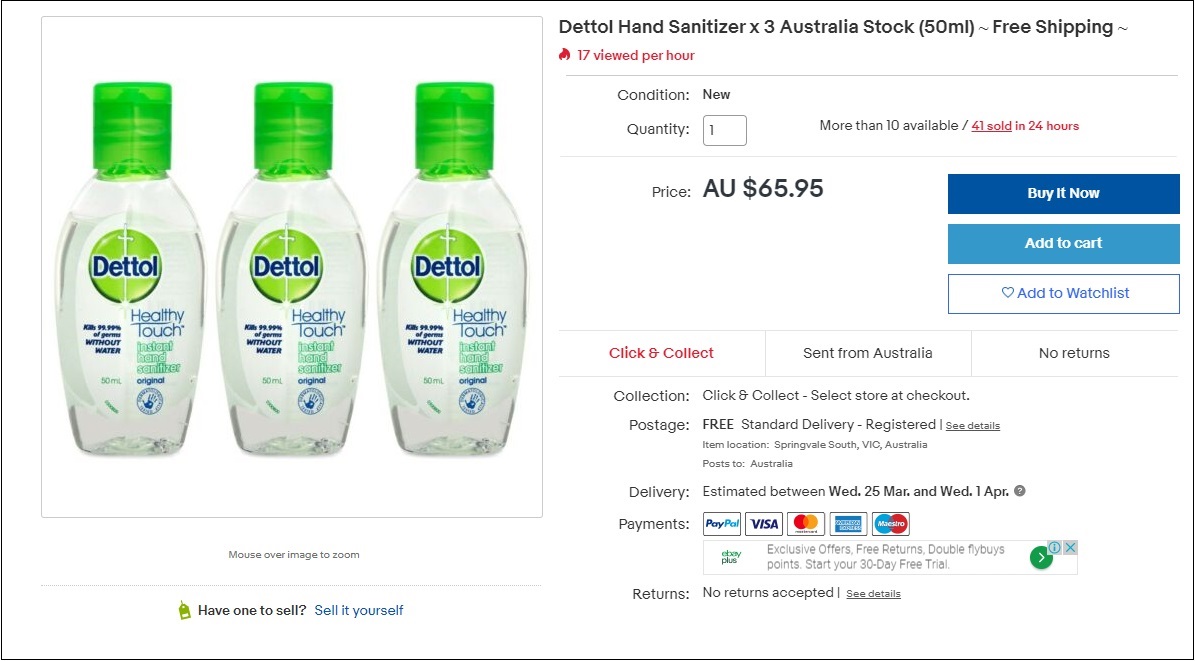

$65.95 for three small bottles of sanitiser (including postage). Yes, that seems reasonable, said nobody. Still, the seller managed to sell 41 lots in 24 hours. Image: eBay

Economic rationalists have justified predatory pricing, with Adam Smith Institute head of research Matthew Lesh – an adjunct fellow with the Institute of Public Affairs – tweeting that “there is nothing wrong with retailers increasing prices”.

“It ensures products can be bought by those who value them the most and helps prevent shortages,” he argued against a flood of angry responses.

With jobs on the line, the government fighting economic catastrophe and front-line healthcare workers struggling to get critical supplies, hoarding and price gouging are frustrating – and aggravating – many.

One man in the US state of Tennessee – who with his brother bought some 17,700 bottles of hand sanitiser from every store they could find across two states – was making “crazy money” selling 300 bottles for up to $106 ($US70) each on Amazon.

Online death threats and investigations by authorities ultimately led him to donate the products to local community groups – and stories of the experience undoubtedly contributed to a new anti-hoarding executive order by US president Donald Trump.

High-tech leaders, low-tech responses

Artificial intelligence and machine learning have proven to be useful price-optimisation tools – helping retailers adjust prices based on demand – but experiments have shown they can also foster cartel behaviour.

Yet despite their arsenals of data analytics and artificial-intelligence tools, technology giants have largely fallen on manual processes to identify and remove listings with unnaturally high prices.

eBay Australia, for one, told CHOICE that staff have been scouring its listings for prices at “grossly inflated prices” – but with hundreds of thousands of overpriced listings, the company’s teams “are struggling to keep up”.

A recent prospective analysis of Amazon pricing by the US Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) Education Fund observed the prices of surgical masks and hand sanitiser were 220 per cent higher than their 90-day average.

Even the average lowest available price over 30 days increased by 18 per cent, and the prices of more than half of the examined products grew by more than 50 per cent over historical averages.

Amazon’s response was recently questioned by a US senator, despite reports that the company has been blocking tens of thousands of listings and threatening sellers with expulsion if they don’t toe the line.

Facebook recently followed suit, augmenting its coronavirus policy with a ban on ads for medical face masks, prohibiting exploitative tactics in ads, and banning ads for hand sanitiser, disinfecting wipes and COVID-19 test kits.

Australian online market Gumtree (which is owned by eBay) did the same, imposing a blanket ban on listings for masks, hand sanitiser, disinfecting wipes, and toilet paper.

Authorities are all but powerless. As the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) recently advised, it “cannot prevent or take action to stop excessive pricing, as it has no role in setting prices”.

Pricing could, the ACCC advised, be “unconscionable” in some circumstances where the product is “critical to the health or safety of vulnerable customers”.

Unconscionable conduct is looked upon poorly by Australian Consumer Law – but case law around the definition of “unconscionable” is subjective, with allegations evaluated on a case-by-case basis and the standard requiring conduct “beyond hard commercial bargaining”.

Ultimately, PIRG Education Fund consumer watchdog Adam Garber said, “when people need something to stay healthy and prevent the spread of a potentially-deadly virus, merchants should follow the Golden Rule, not the money.”