A new bionic eye shows promise as a safe, stable long-term implant for humans which could restore useful vision, researchers at the University of Sydney have discovered.

Called the Phoenix99 Bionic Eye, it is designed to work around the damaged cells in people with severe vision impairment and blindness caused by degenerative diseases.

Known collectively as retinitis pigmentosa, it’s estimated that this affects about one in 3,000 Australians and there have been no cures or even potential treatments, until this development.

The research team behind the Phoenix99 Bionic Eye see this as a promising example of the seamless interaction between humans and therapeutic implants.

As last Friday's annual International Day of People with a Disability highlighted, people with disability face barriers to accessibility and inclusion in society.

The researchers hope that through this technology, people living with profound vision loss from degenerative retinal disorders may be able to regain a useful sense of vision.

“This breakthrough comes from combining decades of experience and technological breakthroughs in the field of implantable electronics,” said professor Gregg Suaning, of this new development.

Inside the bionic eye

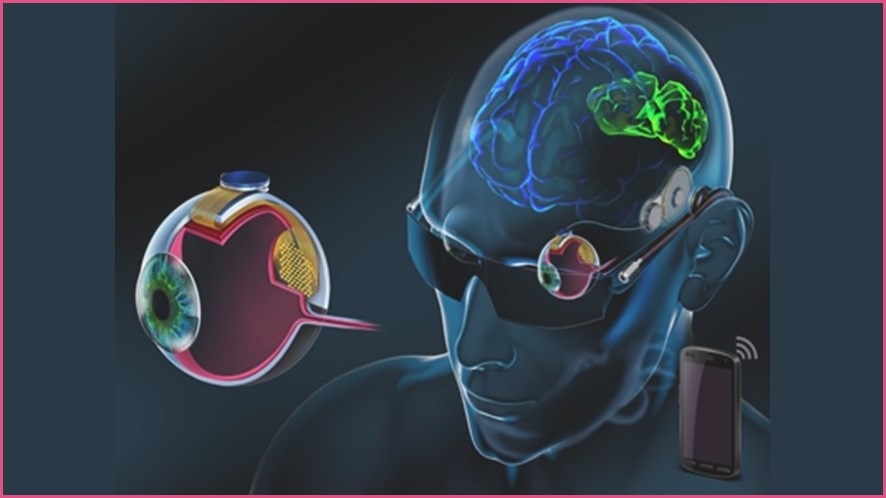

The Phoenix99 consists of two main components, both of which need to be implanted, which then operate in tandem to record and create the images that restore sight.

To address the non-functioning retina cells, a stimulator is attached to the eye and then a communication module is positioned under the skin behind the ear.

For it to ‘see’, a tiny camera attached to glasses captures the visual scene in front of the wearer.

The images are then processed into a set of stimulation instructions that are sent wirelessly through the skin to the communication module of the prosthesis.

The implant decodes the wireless signal and transfers the instructions to the stimulation module, which delivers electrical impulses to the neurons of the retina.

The electrical impulses, delivered in patterns matching the images recorded by the camera, trigger neurons which forward the messages to the brain, where the signals are interpreted as a vision of the scene.

Tricking the brain to ‘see’

In healthy eyes, the cells in one of the layers turn incoming light into electrical messages which are sent to the brain.

However, in some retinal diseases, the cells responsible for this conversion degenerate, causing vision impairment.

The Phoenix99 Bionic Eye works by directly stimulating the retina – a thin stack of neurons lining the back of the eye – bypassing the malfunctioning cells, effectively tricking the brain into believing that light was sensed.

“Importantly, we found the device has a very low impact on the neurons required to ‘trick’ the brain.

There were no unexpected reactions from the tissue around the device and we expect it could safely remain in place for many years,” Suaning said.

The researchers used a sheep model to observe how the body responds and heals when implanted with the device, with the results allowing for further refinement of the surgical procedure.

The team is now confident the device could be trialled in human patients.

“These positive results are a significant milestone for the Phoenix99 Bionic Eye,” Professor Suaning said.