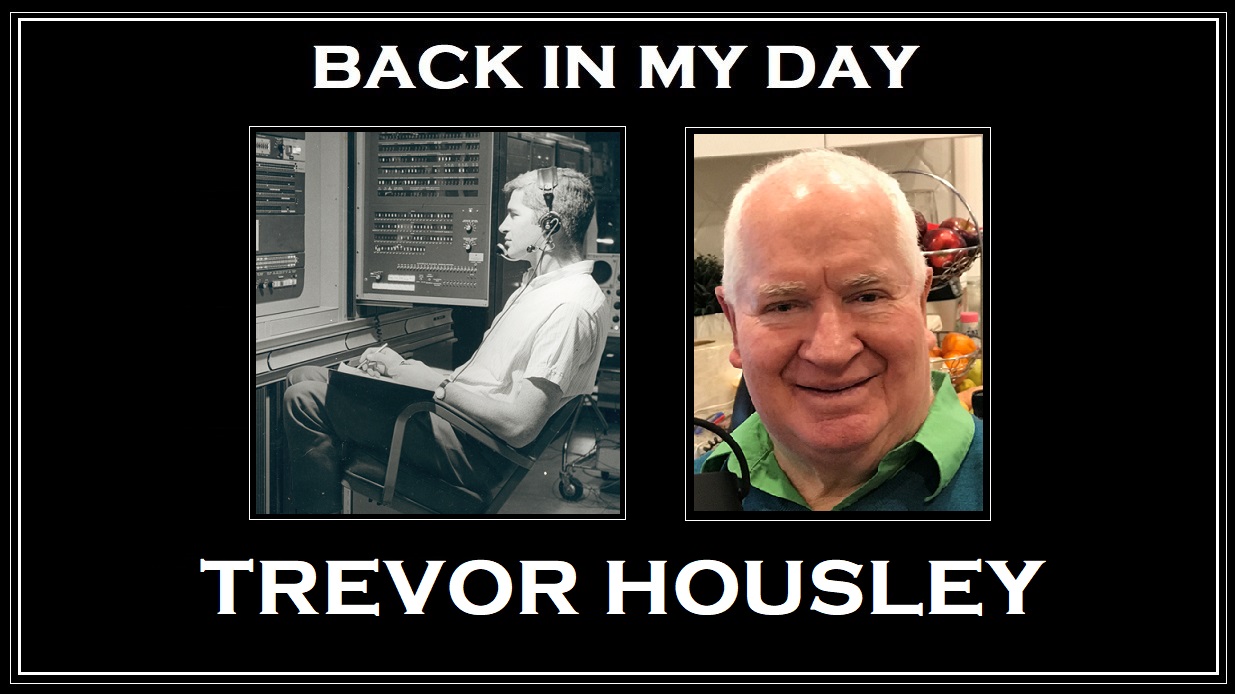

‘Back in My Day’ is an Information Age series profiling some of our older ACS members and Information Age readers speaking about their early days in IT.

This week, we speak with Trevor Housley, aged 80, from Sydney, New South Wales.

How did the IT connection start for you?

I’ve been connected to the telecommunications industry since I was eight years old because my father, also named Trevor Housley, was a highly respected and internationally-recognised telecom pioneer.

So, with dad’s help I started building crystal radios and he’d bring home long reels of wire for me to use as aerials.

But in my teenage years I decided I wanted to make my own mark on the world and enrolled in electrical engineering at UNSW, specialising in computing and automatic control, graduating in 1963.

While at uni, I worked with NSW Railways, where they had supervisory computer systems that controlled the distribution of power across the electric rail network.

For its time, this was a surprisingly advanced digital communication system and was at the leading edge of commercial comms, reigniting my boyhood interest in telecommunications.

Where did this lead?

To NASA – the most exciting job I’ve ever had!

I joined them in 1964, working at the NASA Manned Space Flight Tracking Station in Carnarvon WA, 1,000 kms north of Perth but things didn’t start off so well.

I’d been told the job would involve computers and control systems, but when I arrived, they sent me straight to the Power House, where the electricity for the site was generated.

To connect with computer technology, I’d hang around the tracking and communication system areas where they had a new computer that I learned to operate.

Funnily enough, at uni I promised myself that I’d never become a programmer because of the agony involved in submitting a punched card program to operators, waiting weeks for it to be run, and then receiving a printout that showed it crashed but only revealing the first syntax error.

However, at NASA they were using a UNIVAC 1218, which was the military version of the 418, and there were no punched cards; they wrote programs in machine language and entered them through a console.

Were you able to escape the Power House?

Yes, by writing programs on the UNIVAC 1218 in my spare time I was able to demonstrate my interest in computers and other digital systems and was put in charge of the Digital Command System (DCS) six months later.

The DCS performed the critical function of sending commands to manned spacecraft, such as turning on the radar beacon or firing the retro rockets to bring the spacecraft back to Earth.

Because the DCS was hardwired and didn’t use programming code, it needed continuous physical modifications to the circuitry, which I worked on.

After a year on DCS, I was sent to look after the computer for the AN/FPQ-6 Radar, which had a 10-metre dish antenna that could point accurately to one-five-hundredth of a degree and measure the range of spacecraft up to 51,500 kms away with a precision of 2 metres.

The computer for the radar was an RCA 4101, and it monitored everything, generating data for transmission to the Mission Control Centre in the USA at speeds of 2,400 bps back in 1965, which would have been one of the first examples of data communications in Australia and, in fact, in the world.

The whole space program was based on the use of real time computers and an extensive tracking network that could generate precise information on the whereabouts and status of the spacecraft at any instant.

The real-time computers were able to provide immediate information to the flight controllers when they needed it and the computers were programmed in machine code and occasionally in Assembly Language.

What happened after NASA?

I joined UNIVAC in 1969, after five years with NASA.

This was just three months before man set foot on the moon and I’d predicted that the space business would dramatically decline after this momentous event.

I was proved right, and one of the unique selling points of UNIVAC equipment was that communications capability was built into the system from the ground up, rather than being bolted on as an afterthought.

We put in message switching systems for organisations like OTC, the Australian Post Office and the Navy, an airline reservation system for TAA, a betting system for ACT TAB, and an information system for the NSW Police.

I was involved with most of these systems in one way or another and ended up as Manager of Real Time Systems.

During this time, I wrote my first newspaper article for UNIVAC, published in the Australian Financial Review, for which I was paid $20 and this led to me writing hundreds of feature articles for the computer press.

After talking to some colleagues in 1972 about being a consultant, I started my own consulting business: Housley Computer Communications P/L (HCC).

How did things play out in your own company?

Surprisingly well.

HCC concentrated on Networking and Telecommunications and we established consulting offices in Sydney, Melbourne, and Canberra.

Our clients tended to be big business and government agencies and the kind of work we did ranged from creating a Telecommunications Strategic Plan for a large organisation to determining what kind of PABX a small company should buy.

It turned out that I had some kind of natural ability for training, after being asked by the NSW Police in 1975 to run a five-day course on data communications for their IT staff, which was highly successful.

This led to us putting together a course that would become the flagship data communications course in the Asia-Pacific Region and led to me writing a book in 1979 titled Data Communications and Teleprocessing Systems which was published internationally by Prentice-Hall and sold over 100,000 copies.

The book was used in educational institutions all around the world and translated into Russian, Bulgarian, and Italian.

Meanwhile, HCC is still in business and this year celebrated its 50th anniversary.

In 2005, after a fulfilling but sometimes exhausting career, I retired.

How has retired life been treating you?

Pretty well.

When I was 16, I played in a rock 'n' roll band as the lead guitarist on the North Shore of Sydney and I’ve now resurrected my passion for music.

In 2005 I got back into playing the guitar with a bunch of musos with whom I sat in a circle playing songs at a pub in Balmain on Saturday afternoons.

Now Jocelyn and I entertain people with dementia in nursing homes, where we sing old time songs they’d have grown up with and they always know all the words and can sing along.

What’s your advice for someone considering IT as a career?

Go for it, especially if you’re a bit on the spectrum as I am, as well as being a geeky tech-head.

However, if you’re a people-oriented person, go for it too, because the industry always needs people who can talk to users in an understandable way and develop specs for the tech-heads to implement.