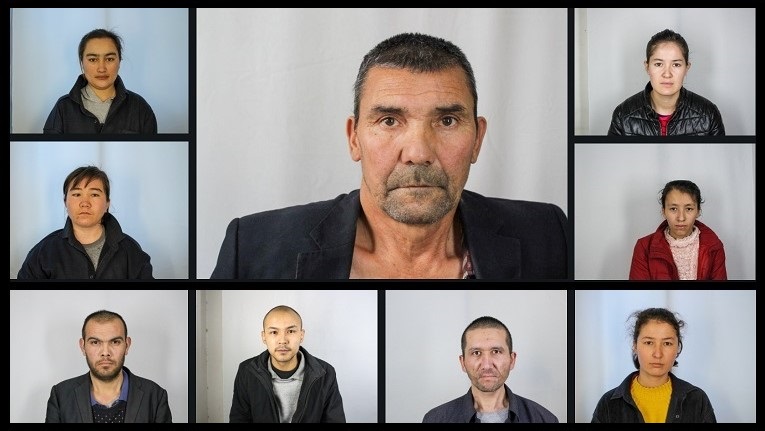

Mugshots of Uyghur detainees, PowerPoint presentations detailing how to stop a prison break, and speeches from high ranking Chinese officials have come to light after a hacker released a trove of documents about concentration camps in Xinjiang to an American academic.

Known as the Xinjiang Police Files, the leak includes unredacted confidential files extracted from police networks inside counties of Xinjiang, a region in China’s northwest which is home to the Uyghur people.

China is accused of numerous human rights abuses against religious minority groups in in Xinjiang through forced labor, arbitrary imprisonment, and so-called ‘re-education camps’.

Some have described it as a genocide. The Chinese government denies all allegations of human rights abuses.

The latest documents leaked by a hacker who “wishes to remain anonymous due to personal safety concerns” show the extent of the detention regime brought upon the Uyghurs.

Importantly, among the files are nearly 5,000 photographs of detainees from Xinjiang’s Konasher county police departments which Uyghurs in Australia and elsewhere have been trawling through for a glimpse of their loved ones.

US academic Adrian Zenz, who was contacted by the hacker, wrote a paper about the files in which he takes a closer look at the documentation of some of the people who were imprisoned.

“The youngest photographed person is a Uyghur girl named Rahile Omer who was first detained when she was only 14 years old,” Zenz wrote.

A police officer was notified about Rahile through the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP) – an app used to conduct surveillance and policing of the Uyghur population which Human Rights Watch published details about in 2019.

A pair of Australian universities were criticised for their connection to this app via research agreements with a Chinese electronics company.

“Her detention had been ‘recommended’ by an IJOP push notification,” Zenz continued.

“The IJOP flagged her as a ‘Type 12 person’, a largely self-referential category denoting persons with ‘danger clues’ because they are in some way connected to an existing police case.”

The youngest person confirmed to be in a re-education camp is Rahile Omer, age 14 when she was detained, nearly age 15 when her image was taken by the police. pic.twitter.com/Sr0W6Rf2aN

— Adrian Zenz (@adrianzenz) May 24, 2022

For Rahile, this meant being sent to a ‘re-education camp’ because she was the daughter of a government official who had been detained during an earlier crackdown on supposed ‘terrorism’ in Xinjiang.

Rahile’s father was also classed as a ‘Type 12 person’. Her mother, meanwhile, had been sentenced to six years in prison for having “disturbed the social order” which Zenz calls “a generic charge handed nationwide to persons targeted by the state”.

The Xinjiang Police Files also contain transcribed internal speeches delivered by high-ranking central government officials such as Chen Quanguo who has been Secretary of both the Tibet and Xinjiang Autonomous Regions throughout his political career.

In a 2018 speech, delivered in the context of the head of a national security body visiting the region, Chen said that police should have shot protesters during the 2009 Urumqi riots – an event which paved the way for the mass digital surveillance and internment that has been occurring in recent years.

Zenz, in his paper, argues that “the scale of Xinjiang’s re-education campaign, the framing of entire ethnic groups as threats, and the attendant extreme preoccupations with security in the campaign’s execution reflect a devolution into paranoia”.

Before the pandemic shut China’s doors to tourists, border authorities had been found installing an app on tourists’ phones that scanned people’s diaries, contacts, and messages checking for banned content – typically anything related to Islam.