The City of Melbourne is exploring different ways of informing citizens about its data collection regime in the hopes of building an ethical, privacy-focused smart city.

A study conducted by the council and Monash University’s Emerging Technologies Research Labs (ETLab) looked at how people engage with sensors placed in public locations that monitor things like foot or bicycle traffic.

The research involved ethnographic experiments in Carlton’s Argyle Square that saw locals interacting with and considering various sensors, including those that track air quality, weather, and the use of assets like benches.

“The actual designs and structures created for Argyle Square drew on our in-depth research with people who use the square,” ETLab Director Professor Sarah Pink said.

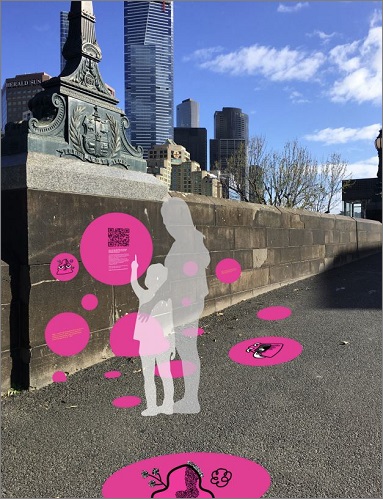

“We used bold colours and created a ‘family’ of characters to encourage playful engagement with the installation.

“People could access the city data through QR codes using their smartphones or learn about how the City collects data through the printed explanatory labels which were aimed at people without digital devices.”

From its research, conducted in 2021, Monash’s ETLab proposed a set of possible ways Melbourne could make its data collection regime more visible through installations, signs, or big stickers around the city.

The goal is to engage the community and gain their trust that smart city data is collected in an open and transparent way.

“To gain everyday trust we need to create technologies that respond to the everyday ethics, values, practices and environments in which people live,” the ETLab researchers wrote.

“We need to realise that it is not the technologies themselves that are trustworthy, but the situations and modes in which they are engaged and the power relationships they are part of.”

An example of proposed ways to inform the public about data collection. Image: supplied

The City of Melbourne already publishes data from pedestrian sensors located throughout the city in near real-time to help the likes of policy makers and civil engineers make informed decisions about how people move around.

The data easily shows how foot traffic around Flinders Street Station, for example, typically peaks at 8am and 5pm – an expected result, but one that is easily quantifiable thanks to pedestrian sensors.

City of Melbourne Lord Mayor Sally Capp said the research project “will build on our open data approach so that we can share our use of technology and collection of data with the community in new and exciting ways”.

“Melbourne is a smart city and we want to work with the community to design, develop and test new ways to share data and knowledge for the benefit of all,” she said.

Cities are increasingly finding a need to be careful about the implementation of smart cities projects as citizens become more aware about the implications of mass data collection and analysis.

In Canada, Google’s infamous attempt to develop a smart waterfront precinct in Toronto became a step too far for many people who were uncertain about giving up more data to the tech giant.

Even when they do get over the line, data collection projects can also be expensive and ineffective, as the Victorian government recently discovered when a project to detect faults in bridges using sensors went bust after running up a $16 million taxpayer bill.