Australian scientists have connected a culture of brain cells to a computer and got it to play video game Pong in what is a major milestone for biological computing.

The experiment, dubbed DishBrain, comprises some 800,000 brain cells cultured from both rodent and human stem cells connected to a software interface.

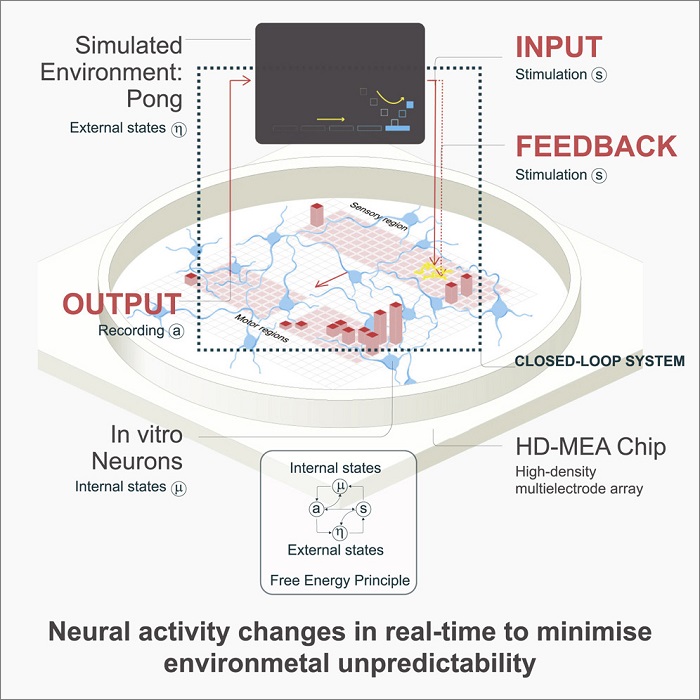

As the ball moves in the game world, its location is communicated to DishBrain by stimulating the cell culture's sensory regions.

In response to the ball, the cells fire one set of motor neurons to move the paddle up, and another set to move it down.

When the ball hits the paddle, the game gives DishBrain’s sensory neurons some nice predictable signals – but when it misses, the neurons are zapped with unpredictable, random feedback.

Because it wants to avoid the bad feedback, DishBrain learns to keep hitting the virtual ball with its virtual paddle.

Andy Kitchen, co-author of a research paper about DishBrain published this week and co-founder of biotech startup Cortical Labs, said the experiment was like a “tiny version of the Matrix”.

“In this case the world isn’t a city so much as it is the Pong video game – but the elements are there,” he told Information Age.

The implications of DishBrain are vast, bordering on science fiction: brain cells could be integrated with robots, with cars, with virtual worlds (like the Metaverse) providing a direct, controllable connection between physical and digital realities that blends the barriers between animal and machine.

A description of the DishBrain feedback loop. Image: supplied/Neuron

In the short term, DishBrain has more clear medical uses.

“Currently lab drug tests on brain cell cultures are limited to whether new drugs kill neurons or simply make them fire but this could tell you what kind of effect the drugs have on cognition,” Kitchen said.

The next tests for DishBrain will validate the extent to which it can be used in this way by experimenting with how the neurons respond to different chemicals.

“We’re trying to create a dose response curve with ethanol,” said Dr Brett Kagan, chief scientific officer of Cortical Labs.

“Basically, get them ‘drunk’ and see if they play the game more poorly, just as when people drink.”

Get drunk, play Pong

Kitchen told Information Age there were some big things on the horizon for DishBrain and the publication of the team's research was just the beginning.

Cortical Labs wants to open access to DishBrain for other researchers and developers, providing remote access and a development kit for experiments in biological computing.

As he puts it, they want to make “cloud for brains”.

“I’ve been interested in AI for my entire career and we really saw that when everyone zigs you have to zag,” Kitchen said.

"In Australia we have a natural advantage in life sciences and there’s an option to completely leap frog what companies like Google and Deep Mind are doing with artificial neural networks and make biological neural networks instead.

“Rather than trying to compete with the big boys in an established field like artificial neural networks, why not try to go a step beyond?”

The idea of growing brain cells in a lab and connecting them to a computer might sound like the beginning of a science fiction nightmare but Kitchen assured Information Age that DishBrain, despite the name, is “not really a brain”.

“It’s a cell culture,” he said. “Yes, it is neural tissue, and it is alive, but it doesn’t have normal natural structures for doing things like your cortex or hippocampus does – mostly it’s the same types of cell without a natural structure.”

“I don’t think these cells have enough qualia to cause significant ethical concerns but it is something to keep tabs on and continue to assess as the research progresses.”