Four of Australia’s largest sports stadiums are using facial recognition cameras to identify and track event attendees without their knowledge, according to a new investigation that found Australian venues have joined a growing and controversial overseas trend.

The Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG), as well as Sydney’s Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG), Qudos Bank Arena, and Allianz Stadium, were all found to be using the technology during an investigation by consumer group CHOICE.

Sydney’s Accor Stadium, Melbourne’s Marvel Stadium, Parramatta’s Commbank Stadium, and Perth’s Optus Stadium were all confirmed to not be using the technology, while the status of the technology at RAC Arena and Suncorp Stadium was unclear.

Given the long history of violent confrontations at soccer matches and other sporting events, venues around the world have adopted facial recognition technologies – which use highly optimised AI algorithms to analyse live video streams of crowds – to pick out banned fans, known stalkers or wanted criminals.

Vendors like Corsight, Oosto, and FaceFirst woo venue owners with promises that the technology can not only spot known troublemakers and identify emergency situations but, as FaceFirst puts it, deliver “better VIP experiences” by identifying and catering to high-value customers.

Corsight markets its technology as “a force for good” and says that its technology takes just 10 milliseconds to check a face in a video stream against a database of 1 million faces – equivalent to scanning 100 faces per second.

Despite its public-order premise, CHOICE consumer data advocate Kate Bower said the problem is that most consumers are unaware of the surveillance and have no chance to opt out.

“One of the main problems from a consumer’s perspective is that they don’t know when facial recognition is being used,” she said, “and even when they do find out, they have no idea what it’s being used for, they’ve got no idea how long their information is stored, how securely it’s stored.”

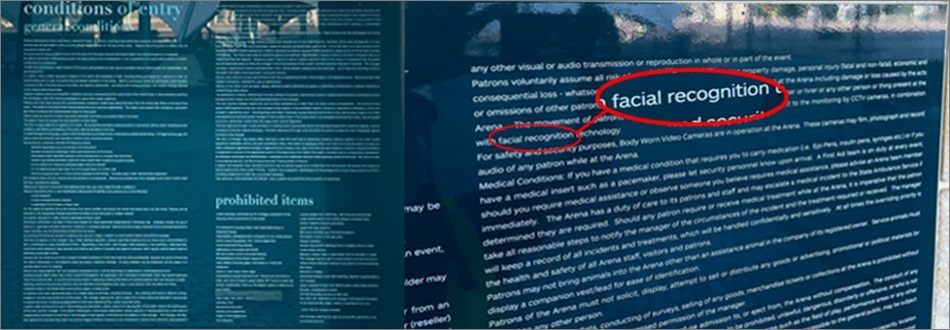

Although many stadiums’ terms and conditions of entry reference collection of “biometric data”, CHOICE warned consumers can only find this by poring over lengthy documents that run to thousands of words long.

You were warned… right? Image: CHOICE

TEG, which leases Quodos Bank Arena and outsources its operation to ASM Global, responded to Bower’s claim that CHOICE is “particularly worried” about data collection in the venue because the company was “leaving the door open for harmful selling and sharing of sensitive biometric information”.

The company “does not collect biometric data” and “does not share any such data with TEG… or any other third party entity,” a TEG spokesperson said, noting that the facial recognition data “is solely utilised for security reasons to identify any persons of interest.”

Facial images, the vendors note, cannot be reconstructed from the facial data produced by the system.

Eyes on the crowd

Human rights activists have moved swiftly to condemn the use of the technology, which has become a core part of crowd control in everything from badminton stadiums to Beyoncé concerts as well as facilitating venue entry, payments, and other applications.

Earlier this year, the discovery that New York City’s iconic Madison Square Garden (MSG) had used facial recognition technology – in this case, to identify and eject lawyers representing clients that were suing the venue – sparked an uproar as dozens of other venues were soon found to be using facial recognition technology for purposes as varied as ticketing and identifying unwanted spectators.

Whatever technological protections may be built into the platforms, surreptitious use of technology has created many firestorms in Australia and elsewhere as legislation races to keep up with its expanding use, litigation ensues, and experts reiterate the importance of using the technology responsibly and ethically.

Despite recent furores over the discovery of face recognition use at the likes of 7-Eleven, Kmart and Bunnings – and criticism of police use of platforms like Clearview AI – facial recognition is being used for large events like the City2Surf run and was considered as a way to help catch problem gamblers entering NSW gambling venues.

The European Union considered but ultimately rejected a ban on facial recognition in public spaces, although privacy advocates renewed calls for controls and groups like Amnesty International are pushing for broader controls after the EU last month voted to ban “abusive” mass surveillance technology and its broad use by police in public spaces.