Exclusive: Members of Australian law enforcement have called for changes to privacy legislation which would allow them to use AI-powered facial recognition and decryption to more easily identify victims and perpetrators of child sexual abuse material (CSAM).

Warning: This story contains references to child sexual abuse.

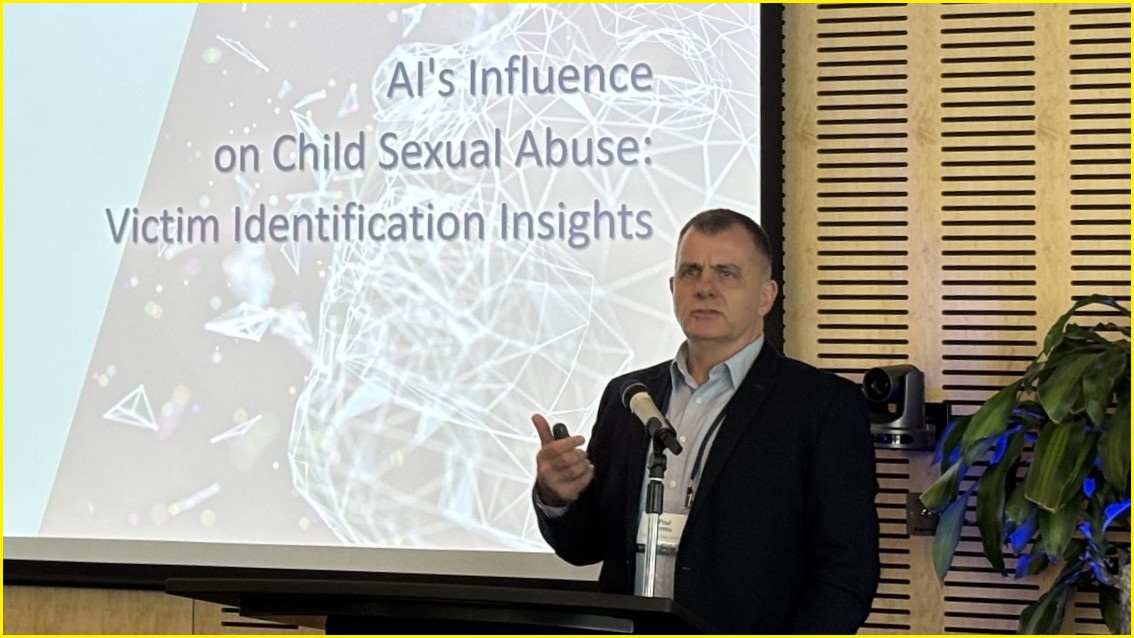

Speaking at the International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children (ICMEC) Australia’s inaugural 'Safer AI for Children Summit' in Sydney on Tuesday, representatives from federal and state police departments voiced concerns over privacy laws and public perception which prevented them from using AI technologies.

Multiple figures admitted the public had a negative view of law enforcement using AI, partly due to previous issues caused by police secretly using AI facial recognition software created by controversial American company Clearview AI.

Members of Australian police departments were caught using Clearview AI’s facial recognition tool in 2020 after the company collected biometric data from the internet and social media platforms without individuals’ consent.

The software has also been used by other law enforcement agencies around the world.

Police ‘trepidation’ after Clearview AI debacle

Simon Fogarty, manager of Victoria Police’s victim identification team, said there was now “a big resistance” to police using AI, but did not mention Clearview AI by name.

“There’s a lot of trepidation in the law enforcement community around using AI, particularly when some of us got burned pretty badly a few years ago in relation to some use of certain products,” he said.

Fogarty argued there was a significant difference between online data scraping tools and AI search tools which could be used offline.

He called for police to foster national messaging around AI to give “some comfort to front-end users on what they can and can’t do” and called for a more positive public narrative around the technology.

Fogarty said that while he believed police needed access to AI tools through improved policies, there were clear moral and ethical considerations needed around facial recognition.

Paul Griffiths, child victim identification manager at Queensland Police, said the use of AI in biometrics was “essential” but a lack of strong regulation had contributed to some police "abusing the powers” of AI, which caused law enforcement to then lose those powers.

A representative from the Australian Federal Police (AFP) said departments needed to be “very transparent” about how they used AI and how it would benefit society.

They said the AFP was “very keen” to work with various jurisdictions to improve law enforcement’s public messaging around AI use, instead of relying on “defensive” communications following media controversies.

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) found in 2021 that Clearview AI had breached Australia’s Privacy Act by collecting facial images and biometrics of citizens.

OAIC ordered Clearview AI to stop and to delete those images, but the company co-founded by Australian entrepreneur Hoan Ton-That has not proved whether it deleted images of Australians or stopped collecting them.

In August, OAIC announced that it would not pursue further legal action against Clearview AI, which was already facing investigations and lawsuits in other countries.

Queensland Police's Paul Griffiths says a lack of regulation contributed to police 'abusing the powers' of AI. Photo: Tom Williams / Information Age

‘We need AI’

Ian McCartney, acting commissioner of the AFP, said while generative AI was allowing offenders to quickly create artificial CSAM, the technology could also help investigators efficiently review large amounts of media and data, "improving investigative outcomes and minimising officers’ exposure to distressing content”.

Generative AI was allowing offenders to both generate new content and manipulate real photos, making it harder to tell which CSAM images were real, McCartney said.

He argued there was an “opportunity” for AI to help with victim identification through facial recognition but said law enforcement must remain “accountable and responsible” in any use of the technology.

McCartney told a parliamentary joint committee earlier this month that “more legislation and more support” was needed to help law enforcement adopt AI technologies.

A victim identification analyst who analyses CSAM for a state police department told the ICMEC summit they wanted to use AI — as some other countries did — to make their work easier, faster, and more accurate, as analysts faced “a tsunami” of material to investigate.

“I understand the need for privacy, but when is the need for privacy more important than the right of children to be free of sexual abuse?” they said.

The analyst questioned why the federal government had not yet introduced regulations allowing law enforcement to use certain AI and facial recognition technologies in CSAM cases, “three years since they pulled the plug”.

“We need AI,” they said, adding that transparency would still be needed around its use.

Long-awaited reforms to Australia’s Privacy Act are expected to improve the protection of children by forcing online services to comply with some new privacy obligations.

AFP acting commissioner Ian McCartney says police must be 'accountable and responsible' in any use of AI. Photo: Tom Williams / Information Age

The encryption issue

End-to-end encryption technology used by many communications platforms including Telegram and Meta’s WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook Messenger systems were “significantly impacting” law enforcement’s ability to identify CSAM offenders, the AFP’s McCartney said.

“We continue to be deeply, deeply concerned that end-to-end encryption has been rolled out in a way that will undermine the work of law enforcement,” he said.

Meta’s regional director of policy for Australia, Mia Garlick, defended the company’s use of encryption on its platforms, and told the summit that Meta assisted law enforcement while also identifying malicious activity in its non-encrypted spaces.

A victim identification analyst from a state police department said most CSAM cases were shared and discussed on encrypted platforms, which made law enforcement’s job more difficult.

They called on technology companies to “push further” to help authorities track down CSAM offenders and victims.

Griffiths from Queensland Police said AI was “the best way to decrypt” encrypted communications and files.

He also suggested the technology could also be used for real-time monitoring and predictive policing by analysing what people posted online, but further regulation would be needed in order to make that possible.

If you need someone to talk to, you can call:

- Lifeline on 13 11 14

- Beyond Blue on 1300 22 46 36

- Headspace on 1800 650 890

- 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732

- Kids Helpline on 1800 551 800

- MensLine Australia on 1300 789 978

- QLife (for LGBTIQ+ people) on 1800 184 527

- 13YARN (for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people) on 13 92 76

- Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467