CSIRAC, Australia’s first computer, is celebrating its 75th anniversary this month and one of the original staff on the system, Professor Peter Thorne took time to share some of its achievements with Information Age.

“It was extraordinary this was achieved here in Australia,” remembers Dr Thorne, who worked as a technician on CSIRAC in the early 1960s, ahead of tonight's Pearcey Foundation Award dinner in Brisbane celebrating the computer’s first operations.

“It was ridiculously slow by today's standards. I mean, about a thousand operations a second, point one of a megahertz,” Dr Thorne reminisced.

“But on the other hand, the only option people had in those days were desk calculators, which could do one operation a second, maybe, if you keyed things in fast enough. Some calculations took three months to do by hand.”

“One well known person in the CSIRO, at the end of a three-month calculation, found he'd made a mistake early on, and he then found out about this computer and what it could do.

"He could do in an hour what took him three months to do, and he could do it again in the next hour and check it.”

“So though today it looks ridiculously slow, it was a thousand-fold improvement on what we had before, just in that one step.

"No wonder people flocked to use it.”

Early days

The machine was Australia’s first stored-program computer and the fourth of its kind in the world, first established at Sydney University’s Radio physics labs before being dismantled and relocated to the University Melbourne.

A product of Australia’s post-war drive to build an industrial and technology base, CSIRAC’s development came on the back of worldwide computing advances in the late 1940s with the project’s leaders, Trevor Pearcey and Maston Beard, being heavily influenced by UK developments such as the Manchester Baby in England and EDSAC in Cambridge that were changing how calculations were performed.

As part of the nation’s technology drive, the then CSIR, forerunner of today’s CSIRO, was rapidly growing and needed advanced computational tools to support scientific research in weather forecasting, agriculture, and engineering.

Pearcey saw the role of computers beyond basic computational tasks, foreseeing “mechanical brains” that could handle routine operations, reading text, and ultimately transforming the nation’s productivity.

Childhood memories

Prior to its move to Melbourne, the father of current ACS President Helen McHugh was one of Australia’s first computer programmers working alongside Trevor Pearcey and Geoff Hill as a programmer on the CSIR Mk1 project.

“There really is such a thing as ‘computer widows and orphans',” remembers McHugh of her father, Brian.

“Because our fathers were so obsessed with their work on the new computers, they just worked massive hours.

ACS President Helen McHugh has fond memories of her father working on early computer technology in Australia. Photo: Supplied

"And so, one of my earliest childhood memories – I think I was four years old – was my mum driving us into Sydney University on a Saturday morning to pick up dad who’d been working all night on a big computational run that required them keeping the machine running, remembering that they ran on valves.

“For these big runs, dad or one of the teams would sleep there. In the big drawers with all the tapes and stuff, the bottom one had a bed in it because should the computer blow a valve, they had to fix the problem, then restart the calculations.”

Digital music ... and calculations

Initially, CSIRAC faced scepticism and budgetary challenges, with many figures at the time arguing Australia should wait for commercial systems rather than developing its own untested technology.

Trevor Pearcey’s view of a having a sovereign capability however was backed by then CSIR Chair, Sir David Rivett, and other key figures in the Australian research community.

When CSIRAC finally launched in 1949, it marked a milestone not only for Australian science but for global computing history.

It became the first computer to play digital music, using the machine’s diagnostic tones.

Melbourne University’s then Professor of Mathematics, Dr Thomas Cherry, quipped “this machine plays better music than a Wurlitzer can calculate a mathematical problem”.

Over its fifteen years of operation, CSIRAC performed critical calculations for meteorology, statistical analysis, and engineering, processing over 700 projects.

Through these projects, it became a powerful educational tool, training Australia’s first generation of computer scientists who would go on to lead the country’s emerging technology sector.

During its final years in Melbourne, the system became the cornerstone of the university’s computational laboratory, training hundreds of professionals who later founded the country’s first computer science programs and technology companies.

Figures like John Bennett, ACS’ founding President and later founder of the University of Sydney’s Computer Science Department, credited CSIRAC with demonstrating that Australia could compete globally in computing innovation.

Through CSIRAC, institutions recognised the significance of computing.

The University of Adelaide, the Commonwealth Bank, and the Defence Science and Technology Organisation saw its potential for diverse applications.

By 1956, the Australian Mathematical Society had formed, partially in response to CSIRAC’s influence, further cementing computing as a respected field.

Obsolescence

By the early 1960s, advances in transistor technology rendered CSIRAC’s vacuum tube-based system obsolete.

Maintaining the machine was costly and time-consuming; spare parts were increasingly scarce, and daily operations required hours of preparation.

The University of Melbourne faced a difficult choice: continue funding the aging machine or invest in a newer, more efficient computer.

Ultimately, CSIRAC was powered down in 1964, ending its operational life but beginning its journey as a preserved relic of computing history.

Professor Thorne attributes CSIRAC’s longevity to a robust design, saying: “When you look at CSIRAC, and I've looked at many of the other early machines, it was better engineered, you know, it was built to military specifications.

"And that was one of the reasons it worked satisfactorily for 15 years."

Preservation

With the decommissioning of CSIRAC, Dr Thorne was part of the team that worked to preserve the system.

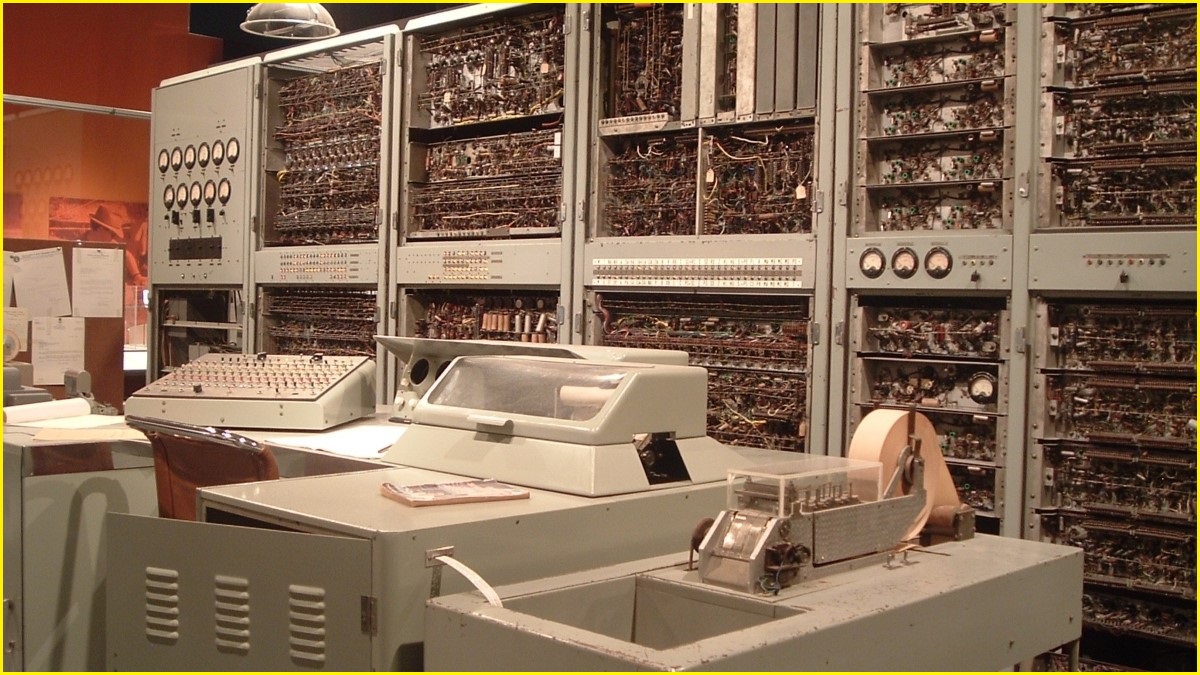

Today, it remains the only intact first-generation computer, housed in the Melbourne Scienceworks Museum as a testament to the early days of digital technology.

It's now on display at the museum in Spotswood in inner Melbourne, however it will never run again, says Professor Thorne.

“People do ask me, why we don't try and make it work again? The reality is that it took a lot of attention to keep it going.

"Even in those days, you'd have to change a lot of the components, because some of the originals are toxic like mercury.

“And if you ever made it work, it would not be original, and then after a while, it wouldn't work again anyway, because it wouldn't be possible to maintain it.

"So you'd have gone from an original ‘non-working computer’ to a ‘non-original non-working computer’.

"Now in England, they build replicas, and they've built replicas of the earlier computers in the world. It's amazing they’ve done it, but this is an original machine of the first generation, and the only one anywhere on the planet. So that's really quite something.”

After its decommissioning there was more than one musical legacy of CSIRAC, Professor Thorne concluded.

“One of the secretaries at Sydney University back in the day was Dame Joan Sutherland.

"In one of our group pictures you’ll see Joan Sutherland sitting in the front row. She had just won the Sun Aria (awarded as part of the 1950 Sydney Eisteddfod) and was about to become La Stupedenda, you know, one of the greatest opera singers in the world.

“I think it's actually fair to say that with the rise of the transistor, CSIRAC was an early bird, and you weren't going to build more of them and sell them to people.

"They did try and put it out to a competitive tender without success.

"But what it did do, it launched it launched people into this career, and it launched our place in the world.”