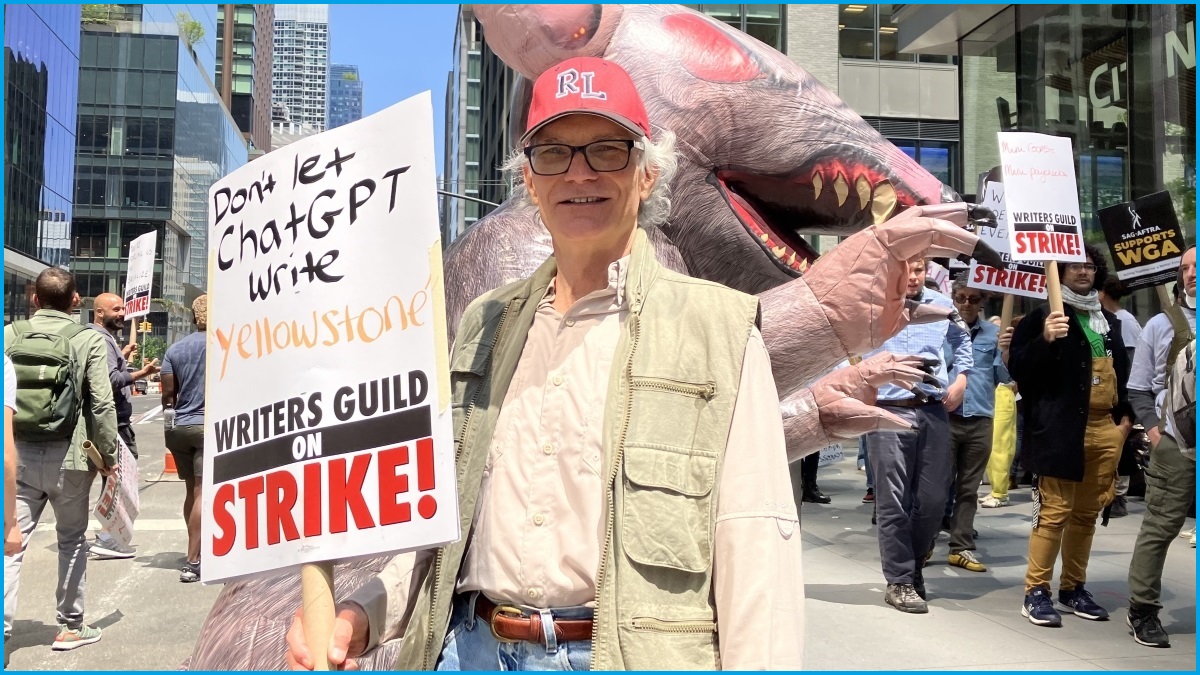

“Don’t let ChatGPT write Yellowstone,” read the sign held by comedy writer Joe Toplyn, as he picketed outside HBO’s office in Manhattan last May.

The Emmy-winner was protesting with the Writers Guild of America, whose members were on strike over pay, job security, and the use of artificial intelligence in the writing process.

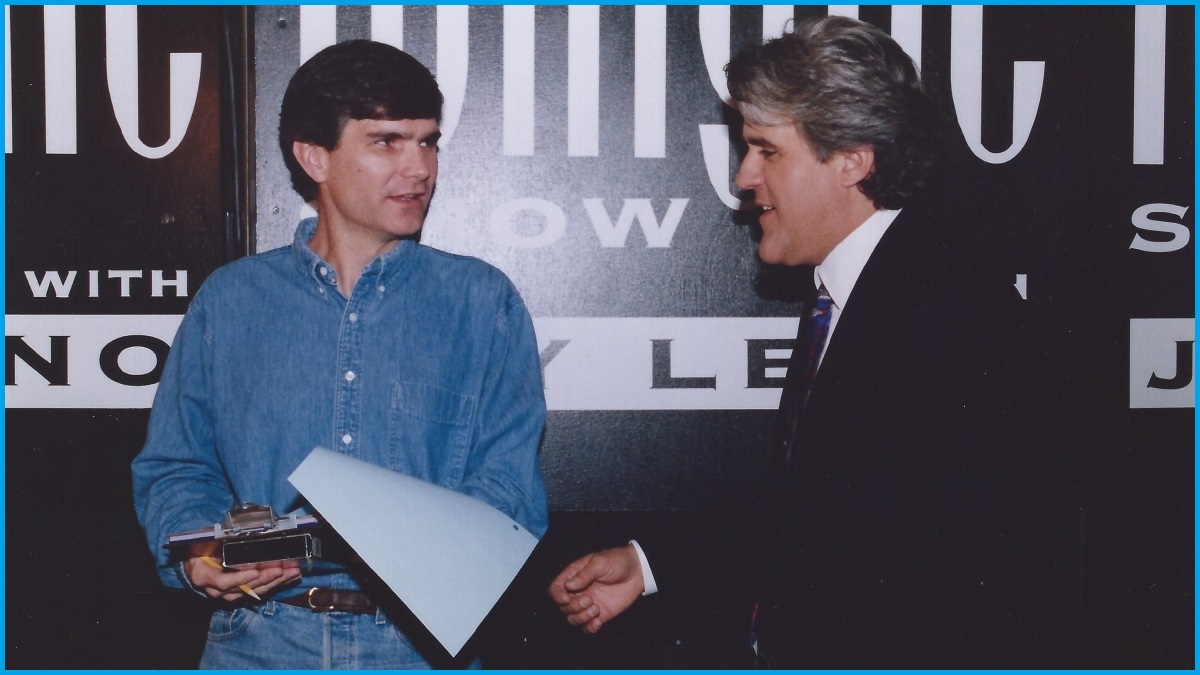

Toplyn, a veteran comic who has written for the likes of talk show hosts David Letterman and Jay Leno, and even the hit TV show Monk, has since taken what some have seen as a controversial step: he has created his own AI comedy writing tool.

In August 2024, Toplyn debuted his “AI-powered joke writer” Witscript, which has already garnered some “very negative, even enraged” comments from some comedians, he tells Information Age.

“Using AI to write jokes is inherently hack,” one social media commenter wrote in reaction to Witscript’s release.

“I cannot fathom a technology I would like less to exist,” wrote another.

Despite the negative comments, Toplyn — who has a Bachelor of Science in engineering and applied physics from Harvard University, as well as an MBA — is confident AI can help people be funnier and allow comedy writers to more easily find inspiration.

Joe Toplyn pickets with the Writers Guild of America outside HBO’s office in Manhattan on 10 May, 2023. Photo: Joe Toplyn / Supplied

'Nobody would ever have to know'

To those taking issue with AI technologies like Witscript, Toplyn points out that some comedians already “buy, adapt, or steal somebody else's jokes”.

He also says he would have used Witscript to help meet his tight TV talk show deadlines, had the technology existed decades ago.

“For comics who do write all their own material, Witscript could be a writing assistant that boosts their productivity so they can add fresh jokes to their act more often,” he says.

“If a comedy writer did use Witscript as a tool, nobody would ever have to know.”

USER: Fun Fact: You would have to click a computer mouse 10 million times to burn one calorie.

— Witscript (@witscript) September 22, 2024

WITSCRIPT: Which is about the same amount of times you have to click 'I am not a robot' just to buy concert tickets online.

While AI large language models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT are not known for being naturally humourous, Toplyn says Witscript — which uses ChatGPT but is also trained on his own joke-writing algorithms — is more effective.

“Witscript is funnier than off-the-shelf chatbots because it mimics specific steps that humans use to construct jokes,” he says.

Toplyn believes AI does not pose much of a threat to professional comedians — he argues it can actually make them more productive and can even help non-professionals be funny.

Witscript, which requires a monthly subscription, has already attracted the interest of people outside of the comedy industry, Toplyn says.

“As far as I can tell, they are people who want to be funny but don't have the time or skill to write jokes themselves and can't afford to hire a professional to supply them,” he says.

Other AI comedy tools have made similar promises, such as PFFT, which was “not created to replace human comedians” but “to make their lives easier and to give us all more laughs”, according to its creator Jeff Ganim.

However, Toplyn admits that “for the foreseeable future, comedy-savvy humans will be needed” to decide which AI-generated jokes are the funniest, as sometimes even Witscript's quips just “don’t work at all”.

USER: Ikea gathered 2,052 employees at its first store in Sweden to hold the world's largest pajama party.

— Witscript (@witscript) September 3, 2024

WITSCRIPT: It was a great success until everyone realized they had to assemble their own beds.

While Witscript is currently only available to people in the United States, Toplyn says he is tailoring it to other markets and sees merit in the system potentially being used to make other AI models funnier.

“A sense of humour would make artificial companions more relatable, so they could possibly help alleviate the problem of human loneliness,” he says.

“… I don't worry that Witscript will just mimic existing comedy and not be original enough.

“Almost all of Witscript's output consists of jokes, and attempted jokes, that I've never seen before — and I've seen a lot of jokes.”

Joe Toplyn with Jay Leno at the Tonight Show, February 1995. Photo: Joe Toplyn & NBC / Supplied

Can AI help us understand humour in a new language?

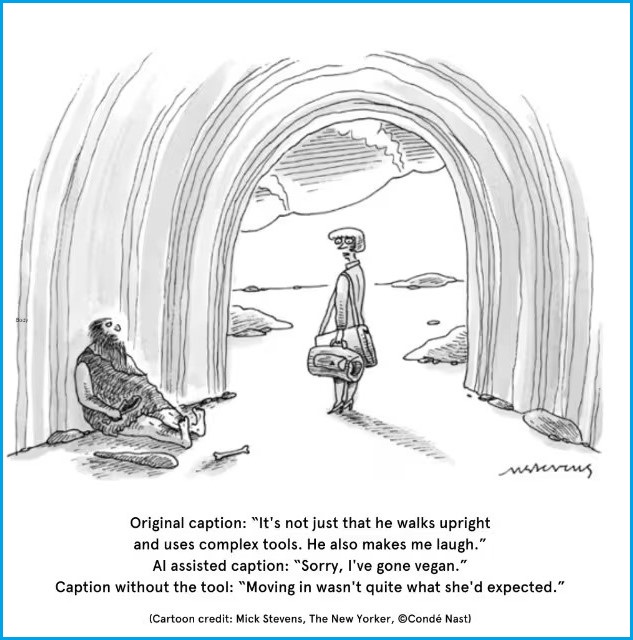

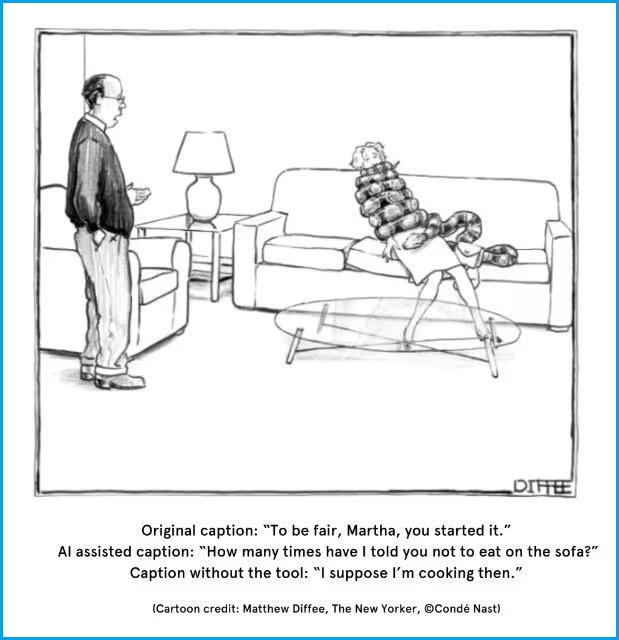

University of Sydney researchers revealed in April they had created an AI-assisted application which they said allowed people — most notably those for whom English was not their first language — to improve their humour by coming up with funny captions for a series of New Yorker cartoons.

Dr Anusha Withana, a senior lecturer in computer science at the university, oversaw the project.

He says the research was partly inspired by his own personal experience as a Sri Lankan man attempting to grasp the cultural references and language which are so important to Australian humour.

“The sense of humour changes so much between people from different backgrounds,” he says.

“I had numerous occasions that I would say something that I believed was funny, and that has worked in a different audience and made people laugh, completely bomb.

"Then you feel like, ‘What went wrong?’

“So I thought, ‘Maybe we ought to check how people from different backgrounds react to or generate humour, and how this sort of tool relates to different people.’”

The app the researchers created utilised an AI-trained algorithm which had analysed descriptions of cartoons, so that it could suggest unexpected and incongruous words which could inspire funny captions for a particular illustration.

In total, 20 people with little experience writing cartoon captions were tasked with writing 200 of them using inspiration from the AI tool, and another 200 captions without any assistance from it.

When a separate group of 66 people rated how funny the captions were, the researchers found the jokes written with their AI-assisted tool were “significantly funnier” than those written without it.

Image: The New Yorker & The University of Sydney / Supplied

“What we found out is it helps people to ideate,” says Withana, who believes people feel a sense of ownership over the jokes they come up with because the algorithm only supplies a few words for inspiration.

“It’s not necessarily the algorithm being funny — it's just helping people to get started, right?

“It's like getting out of writer's block in a sort of way, so it helps you to understand some narratives, ideate and come up with things that you normally wouldn't,” he says.

Non-native English speakers got 43 per cent closer to how funny the winning captions were in The New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest, according to the study, while all of the AI-assisted captions were 30 per cent closer to the winning captions overall.

What’s more, almost half of the jokes written with the help of the app were found to be funnier than the original cartoon captions chosen by The New Yorker, the researchers said.

“We didn’t expect it to be that much of a difference, but it turned out it is,” says Withana, who notes that comedy is still subjective and most of the original cartoon captions were written in a US context.

He says the major improvement for non-native English speakers was a “very interesting and quite surprising” discovery, and he hopes similar tools will end up being used in industries such as education.

Image: The New Yorker & The University of Sydney / Supplied

The idea for the research project came from student and cartoonist Alister Palmer and was led by Hasindu Kariyawasam as an undergraduate research intern.

"Humour is such an important way to relate to others,” Kariyawasam said when the research was released.

“It is also important for emotional wellbeing and creativity, and for managing stress, depression, and anxiety.

“As a non-native speaker myself, I found the system helped me write jokes more easily, and it made the experience fun."

With great AI power comes some AI censorship

Rapid developments in LLMs and AI chatbots have made the technology more approachable and useful to the public, but these increasingly powerful systems still have issues when it comes to comedy.

Piotr Mirowski is a research scientist at Google’s AI lab DeepMind and the co-founder of Improbotics, a theatre and comedy improvisation group in which humans perform alongside an AI chatbot.

He says the ever-increasing fluency of LLMs such as ChatGPT is causing a “dramatic change in public perception” by raising people’s expectations of the technology, while also making AI outputs more sanitised.

Piotr Mirowski performs with Improbotics as part of Brighton Fringe in May, 2024. Photo: Improbotics & William Ranieri / Supplied

Mirowski says absurdist humour, which was previously used quite often due to incongruent or seemingly random suggestions made by earlier AI systems, would “no longer cut it”.

“Massive adoption and their ease of use enables anyone to interact with an LLM to try to write comedy,” he says.

“But the fact that LLMs became safer to use comes with its very specific drawbacks for comedy.”

Such drawbacks were highlighted in a study published in June by Mirowski and three other DeepMind researchers, who asked 20 professional comedians who already used AI somewhere in their creative process to use an LLM like ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini (then called Bard) to generate new material.

“Several comedians we interviewed found issues in how safety filtering of LLMs made those LLMs very dull, and how they could not explore more personal subjects and edgy material,” Mirowski says.

As the study found, “Participants noted that existing moderation strategies used in safety filtering and instruction-tuned LLMs reinforced hegemonic viewpoints by erasing minority groups and their perspectives, and qualified this as a form of censorship.”

Most of the study participants also found LLMs were not successful as creativity support tools.

One of the participants wrote:

"[The AI] would be very politically correct and not really taking any risks … as this sort of bland kind of cruise ship-style entertainer, or maybe like something you’d see in comedy from the ‘50s and ‘60s, but less racist."

The 20 comedians took part in 3-hour workshops on comedy writing session with LLMs, HCI study to assess the Creativity Support Index of AI as a writing tool, & focus group: on ethical concerns about bias, cultural appropriation, censorship, cultural erasure, copyright concerns. pic.twitter.com/RYhCBaULRV

— Piotr Mirowski (@MirowskiPiotr) June 4, 2024

Mirowski says that while LLMs are now highly capable at completing language tasks, when it comes to jokes “one can also argue that they merely execute well upon the premise of a joke that is effectively provided by a human”.

He says "there is still a huge element of human choice” in the shows performed by his improv group Improbotics because “the actor picks the funniest line and decides on timing”.

Improbotics has also found that while many audience members were left feeling more excited about using AI tools for creative storytelling after seeing one of the group’s shows, many others were less optimistic.

“Our interpretation was that the audience got a sense of how complex human comedy was for AI systems,” Mirowski says.

“For me, the most difficult task for a robot would be to understand the subtle cultural context of what makes specific audiences laugh, at specific parts of the show.

“… AI has no lived embodied experience to which we humans can relate to, and where comedy often comes from.”