An investigation by a consumer advocacy group has revealed the extent to which Australia’s favourite cars may be monitoring drivers, analysing privacy policies from Australia’s top ten car brands to learn more about the data they collect and how it can be used.

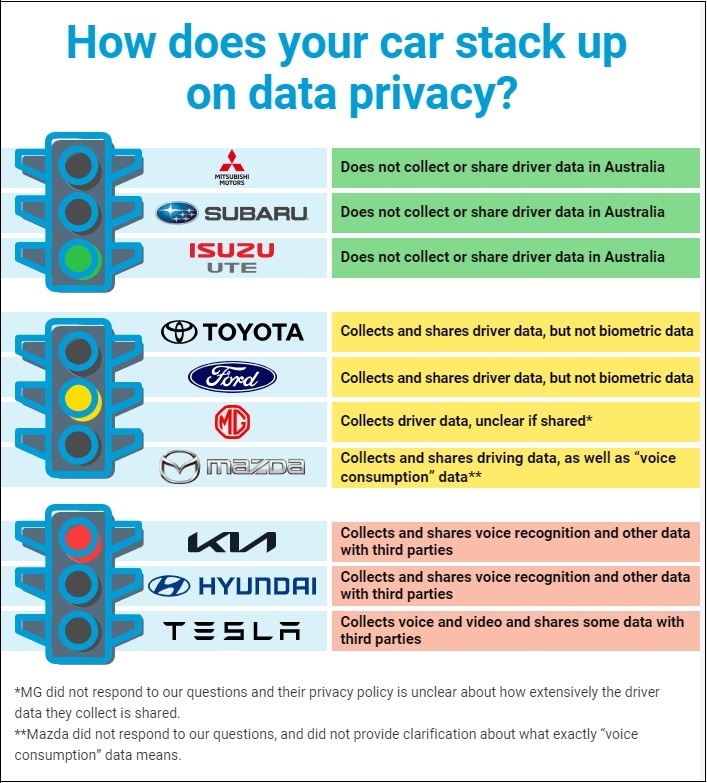

According to Choice, Kia, Hyundai and Tesla ranked worst overall.

“Kia and Hyundai both collect and share voice recognition data with third parties, along with other information,” said Rafi Alam, senior campaigns and policy advisor at Choice.

“Tesla takes it one step further, collecting ‘short video clips and images’ captured from

the camera inside the vehicle, and shares some data with third parties,” Alam explained.

Toyota and Ford were found to share non-biometric data, while MG and Mazda were unclear about the extent of their data sharing.

The seven worst-performing brands all made use of connected features, which use the internet to enable remote operation and security functions.

Only three brands — Mitsubishi, Subaru and Isuzu — don’t collect or share data on Australian drivers.

The wheels have eyes

James Eling, managing director at cyber support company Extreme Networks, said many consumers simply aren’t aware of the data being collected.

When it comes to the tech in modern cars, he said, they can be imagined as “software that has a car wrapped around it”.

“You’ve got cameras inside the vehicle, and you’ve got voice-activated systems,” he said.

“The vehicles collect an inordinate amount of data, and we don’t really know where that data is going or what it’s being used for.”

While car companies suggest consumers can simply opt out of data collection, Choice said this isn’t enough.

In many cases, drivers are automatically opted in, with data-sharing details hidden behind complex privacy policies.

"Opt-out is not the answer; you should have to opt-in to some of these features if you want them,” said Dr Vanessa Teague from the Australian National University's College of Engineering, Computing and Cybernetics.

“Many of these other features should simply be illegal.”

Source: Choice

Who’s looking under the hood?

“People are getting more and more creative with the way they use data, whether it's for good, whether it's for making money, or whether it's for evil,” said Eling.

For example, insurance companies in the states have been using connected vehicles to collect driver insights, which they then use to surge premiums.

Meanwhile, Ford has patented a system which uses trip data and in-car conversations to deliver targeted ads.

Consumers should also be concerned about their data being shared with third parties, some of whom may be beyond the reach of Australian privacy laws.

“As the data gets shared, how certain can we be of the controls that are in place to make sure the data is used in a way that isn’t detrimental or isn’t privacy invading?” asked Ned Farhat, Director of CyberSage and cyber security and digital forensics expert.

While companies may claim they protect customer data by anonymising or de-identifying it, Teague called this “complete baloney”.

"The idea that you can de-identify an image, or that a voice is de-identified, it's nonsense," she added.

Hot-wiring your data

With so much data on offer, hacking is another concern for connected cars.

Eling explained this includes supply chain risks, where manufacturers who have been hacked might roll out a software update that can be accessed via a hidden ‘backdoor’.

“The biggest mistake we make is assuming we know what the risks are,” Farhat added, explaining new vulnerabilities are identified all the time.

In September this year, cyber security researchers disclosed the existence of now-patched vulnerabilities in Kia vehicles, which allowed remote access to cars using only the licence number.

Connected cars may even pose a threat to national security.

According to Eling, overseas governments may have the power to request access to Australian data, which could be used to track a person of interest, see which roads or bridges are most used or even access video from vehicles accessing critical infrastructure.

Concerns of this nature recently led the US to announce plans to ban Chinese-made software and hardware from American roads.

“People are like digital snails, we leave trails everywhere,” Farhat explained, pointing to incidents like the 2018 Strava debacle, where user activity inadvertently revealed the location of secure military bases worldwide.

“Get access to their car data, and all of a sudden, I’ve exposed a facility, or block or office that shouldn’t be public information.”

Privacy laws stuck in the slow lane

Alam explained Australia’s out-of-date privacy laws simply cannot protect consumers in our digital world.

"At the moment, businesses are able to write their own rules through their privacy policies.

“As long as a customer 'consents' in a way the seller decides is sufficient, the business can mostly do what it pleases with our data," said Alam.

Farhat agreed, adding, “We have the Privacy Act, but you’ve got to have enforcement, and the penalty has to hurt.”

He pointed to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulator (GDPR), which has the power to fine a company up to 4% of its total global turnover.

“You cop one of those slaps, you’re going to pay attention next time.”

Eling cautioned drivers to be aware of the technologies in use, adding, “I think we need to be careful about what we do and say in a car, and we need to be mindful of the fact that it is being surveilled.”

Finally, Farhat advised people disable the connected services in their vehicles or share their

concerns with their manufacturer via social media or by post.

“When you do that, the company’s getting a message, and we’ve got to send that message.”