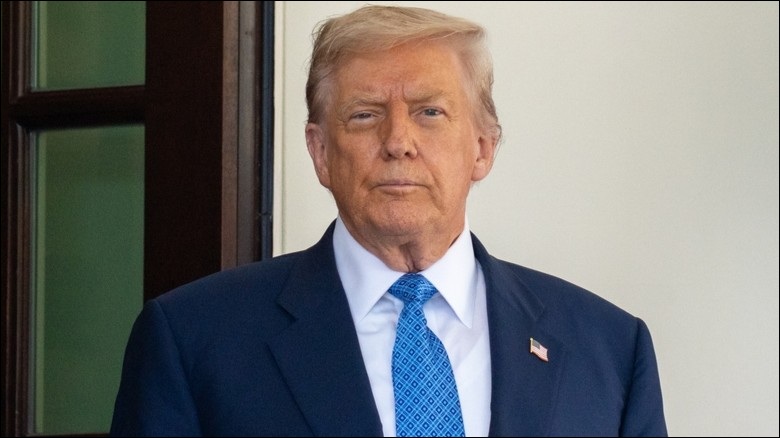

Australia could benefit from Donald Trump’s withdrawal of United States support for 66 UN and independent climate change, cybersecurity and digital policy groups, an expert has said after Trump slammed the organisations as “contrary to the interests of the US.”

Issued in a January 7 presidential memorandum, Trump’s proclamation comes a year after Executive Order 14199 directed the US Secretary of State to review US participation in international “organisations, conventions and treaties.”

While the UN was founded “to prevent future global conflicts and promote international peace and security,” it said, some UN bodies “have drifted from this mission and instead act contrary to the interests of the US while attacking our allies and propagating anti-Semitism.”

The UN Human Rights Council, UNESCO and UNRWA were singled out in the original order, but the newly released final list puts 66 other global organisations on notice that the US will immediately withdraw its political and financial support “to the extent permitted by law.”

The list includes 31 United Nations bodies including the International Law Commission, Economic and Social Commission (ECOSOC) for Asia and the Pacific, UN Energy, UN Oceans, UN Alliance of Civilizations, and UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Disrupting global digital policy development

Given that the US contributes 22 per cent of the UN’s $5.15 billion ($US3.45 billion) regular budget, its reduced financial support will further pressure the global body – which is laying off staff and faces a “race to bankruptcy” with nearly a quarter of member states in arrears.

The US decision to abandon the global technology development and governance bodies – many of which promote regional development through AI, digital infrastructure, and green technologies – will put the squeeze on a range of innovation and digital advocacy programs.

The remit of ECOSOC for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), for example, drives spacetech research to improve digital connectivity and reduce regional disaster risk while the UN University thinktank’s UNU-Electronic Governance (UNU-EGOV) manages tech policy research.

UNCTAD, for its part, is a global data clearinghouse and researches the trade impact of tech like AI, robotics and biotechnology while the UN Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) delivers training on cybersecurity, AI, data science, IoT, and other specialised areas.

Non-UN multinational partnerships are likely to be equally challenged by the US withdrawal, with the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise (GFCE) likely revisiting the commitments in the three-year strategic plan it delivered just a month before Trump’s announcement.

“The US has been an important contributor to international cyber capacity building efforts over time,” a GFCE spokesperson told Information Age while thanking the country “for 10 years of extensive commitment and constructive involvement.”

“The GFCE remains operational and the community remains fully committed to its shared mission of strengthening cyber capacity through practical cooperation, knowledge sharing, and multistakeholder engagement.”

Also named are the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE) which taps cybersecurity skills to counter disinformation, election interference, and nation state cyberattacks, while the 15-year-old Global Counterterrorism Forum (GCTF) fights online terrorism.

And the US withdrawal from the Freedom Online Coalition (FOC), whose now 41 members advocate for global digital inclusion and the preservation of human rights over an open Internet, could tip its philosophical axis towards more privacy-minded European nations.

An opportunity for Australia?

Australia has played a leading role in many of the UN and independent collaborations on Trump’s chopping block.

For example, it has supported ESCAP and UNCTAD with $4.5 million ($US 3 million) to help developing APAC nations build digital trade policy, supporting the eTrade for Women entrepreneur program, and promoting blockchain and paperless digital trading.

It also sponsored UNCTAD’s 2025 eTrade Readiness Assessment for Indonesia, supporting digitalisation of small businesses in that country and advocating for Indonesian adoption of digital payments systems aligned with Australian and global regulations.

In today’s global collaboration environment, the loss of one of Australia’s leading research and innovation partners is on the radar of Australian Academy of Technological Sciences & Engineering (ATSE) acting CEO Peter Derbyshire.

“Research and innovation is such a global activity and requires that international collaboration to be effective,” he told Information Age, “and I’m not sure any one country can really step up and cover what the US helps fund in those areas.

“When they start withdrawing from those global communities,” he continued, “it does concern us how it will affect our own capacity to do research and innovation…. and it makes it harder to negotiate when one of our closest partners is no longer in the room.”

Yet Australia has considerable international clout, he added, with programs like the ATSE run Global Science Technology Diplomacy Fund pumping millions into Asia-Pacific high tech partnerships and government recently eyeing the Horizon Europe innovation fund.

This pedigree could turn the US created leadership vacuum into an opportunity for Australia’s digital policymakers to assert themselves on the global stage, Derbyshire said.

“We’re really keen to see how Horizon Europe and the Australian government can mesh together,” he said, “to provide an opportunity for our south-east Asian partners to look at Australia as a go-between between Horizon Europe and these international collaborations.”