The brand new content-streaming service from Disney, owner of Marvel, Star Wars and Pixar, won a huge number of new members on its launch.

Ten million signed up to Disney+ (pronounced Disney Plus) on its first day of operation in the United States last week, a result sufficiently above expectations that Disney stock jumped seven per cent.

In early November, Disney CEO Bob Iger told investors Disney had an “all-in” commitment to the service and a “determination to launch big and scale fast.”

Unfortunately, the launch did not go to plan, with widespread reports of glitches and customers being unable to log in to their accounts.

Today, Disney+ streams its first pixels in Australia.

It jostles into a crowd of local streaming services: Netflix, Stan, Foxtel Now, Kayo, Amazon Prime Video, Ten All Access, ABC iView, SBS On Demand, and the rest.

In America the list of streaming services is longer still. Hulu and HBOMax are established competitors.

Apple TV has begun shakily, but is backed by that company’s hundreds of billions of dollars in cash reserves and should not be discounted.

Is competition good for consumers?

In 2017 Netflix CEO Reed Hastings famously said the major competition for his service was “sleep.” With Netflix increasingly hemmed in by large players, he has changed his tune.

“Disney is going to be a great competitor,” he told investors on the most recent earnings call. “Apple is just beginning, but they will probably have some great shows too.”

The proliferation of services is likely to drive down prices. Disney is charging just $AUD8.99 in Australia and $US6.99 in the US.

Consumers should be throwing a party, right? Nope.

Budgets won’t stretch to cover all these services. Choice is not always the consumer’s friend – especially when each choice comes with a subscription. Consumers already feel strained.

Dear Apple, Hulu, Netflix, Disney, Amazon, CBS, NBC, and everyone else trying to create a streaming service: we're not going to pay for eight of these. Work it out.

— Dan Koboldt Puts Science in Fiction (@DanKoboldt) November 9, 2019

In the proliferation of choice, some see opportunity.

How long until some genius bundles all the streaming services and just reinvents cable?

— Simon Holland (@simoncholland) November 14, 2019

This is an appealing idea – that we are at the peak of a cycle of fragmentation which will be reversed by a single entity that solves all our needs.

There are clear economies of scale in a TV streaming business – a service should hire all the best writers, get all the best shows, buy all the best old movies, win all the customers, and link it all up. It makes sense to us, the consumer. Will this convenient dream scenario happen?

Here’s the thing about markets. They provide bounteous choice. Even when that is not what suits the consumer.

To understand why we will get competition even if we don’t want it, imagine how any dominant streaming service would set its pricing. It has a single dominant product everybody wants and no viable competitors. That means pricing power. And lots and lots of profit. Like blood in the water, profit attracts competitors.

Unless the dominant streaming service commits to set prices at zero, competition in this sector is going to be exceedingly vibrant for a rather long time.

A short detour into the history of print

The history of print media shows what can happen as markets move online. One or two dominant newspapers per city gave way to dozens of competitors, all struggling to stay afloat. Competition has been brutal, with huge losses at major news organisations. The sector has been transformed by bankruptcies, mergers, and take-overs. Old competitors like the Guardian and New York Times have been shaking up new markets.

Free news has proven to be a formidable model. The top four site for online news are News.com.au, ABC, Nine and the Sydney Morning Herald. The top three of which are totally free, the fourth has a porous paywall.

The consumer experience is fragmented and frustrating. Most of what people want to read remains behind paywalls. This tempts news services like the Washington Post or The Economist to offer metered models, trying to find the sweet spot between maximising revenue and audience.

But metered models, where readers are permitted few pieces each month, can both frustrate consumers and erode profits. There is no settled equilibrium, no one approach that meets all needs.

Not to mention messaging apps

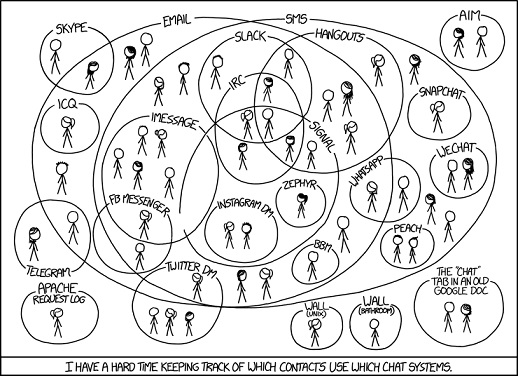

Another market offering more choice than consumers might prefer is messaging apps. In an optimal world we are all on one ideal system. In real life, you have to remember whether your interlocutor prefers Facebook Messenger, Whatsapp, SMS, Signal, Telegram, or email.

Image credit: XKCD

The network effects of a messaging service should do far more to discourage proliferation than the economies of scale that come with a streaming service. That said, the economies of scale of streaming service are extreme.

Once Netflix or Disney own a show they can give it away to all their customers for essentially no additional cost. If they can obtain a monopoly position, the profits that flow could be almost unprecedented.

That is why Netfllix is investing US$15 billion in content in 2019 alone. And why Disney is offering its product at such a low price. All the other competitors are nipping at their heels and it’d be foolish to discount their potential. Few will give up.

Like Game of Thrones (a show neither of those big streaming contenders have in their arsenal) there are certain to be a few surprises along the way, and a lot of blood shed before the end.