The government has begun work on reforming national electronic surveillance legislation a year after an independent review called for extensive changes to existing laws.

Home Affairs Minister Karen Andrews released a discussion paper about the reforms on Monday saying the changes will bring clarity to the legal framework that was described in the lengthy Richardson Review into the national intelligence community as “unnecessarily complex” for both agents and the broader public.

“The government’s proposed reforms will better protect individuals’ information and data, ensure law enforcement and security agencies have the powers they need to investigate serious crimes and threats to security, and clearly identify which agencies can seek access to specific information,” Andrews said in a statement.

“The government will balance the need for agencies to have the powers they require to protect Australians, while ensuring these powers are subject to robust controls, safeguards and oversight.”

According to Home Affairs, the reform will try to bundle electronic surveillance laws into a single act that reflects “what it means to communicate in the 21st century”.

It is seeking public comment on the discussion paper until 11 February 2022 and asks questions about how the laws currently affect privacy, to what extent service providers should have to store communications data, the nature of that data, and how law enforcement can access to it.

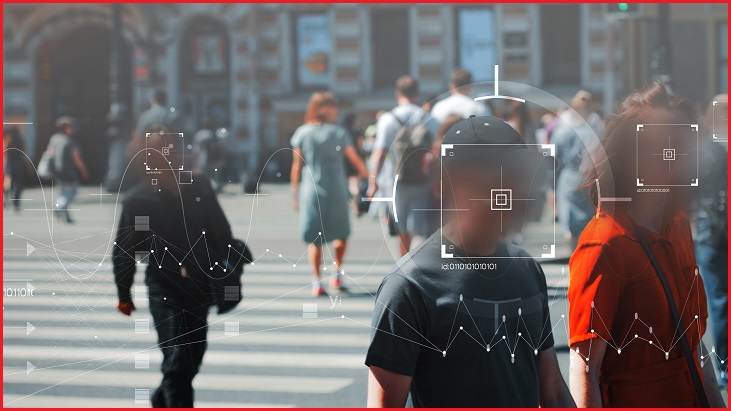

They are questions which strike to the core of this government’s national security agenda which has seen the introduction of consecutive controversial pieces of electronic surveillance legislation including the metadata retention scheme, the encryption bill, and most recently the identify and disrupt bill.

Each of these laws has been routinely criticised for a range of issues from concerns that they fuel conspiracy narratives about surveillance to the threat that the laws will scare off tech businesses from setting up shop in Australia.

The $18 million Richardson Review – which is over 1,300 pages long – noted how the national intelligence community found the current laws to be “ad hoc, piecemeal and inconsistent”.

One striking fact from that review was just how much the laws, designed before the digital age, had bloated as governments repeatedly patched holes and increased the size of the relevant acts from a total of 729 pages at their inception to 2,310 when the review was conducted.

The complicated laws and requirements has likely helped contribute to administrative bungling such as the period of months in 2015 when ACT Police didn’t notice it was lacking a delegated officer to authorise metadata requests; as a result, it illegally accessed metadata over 3,000 times.

The Richardson Review was handed down with 203 recommendations to the government, most of which it agreed upon.