You are being watched.

Everything you do online is being captured, stored and analysed in order to determine your personality, preferences, and predict your behaviour.

In this special 3-part Information Age series, we look at the ways your online activity is being tracked and some of the steps you can take to control your personal data.

Part I: Browsers, trackers, and cookies

The first step in taking back control of your data is learning more about who is looking at what and when.

Let’s start with cookies.

These small packets of data are stored locally on your device and get passed between web applications for all sorts of good reasons like authentication.

Remember Netscape? It patented the cookie in 1995 as “a method and apparatus for transferring state information between a server computer system and a client computer system” after employee Lou Montulii invented the process.

Cookies were an important solution to early web problems – such as the ability to make shopping carts that keep a persistent list of chosen items during a browsing session – and remain an integral part of internet use to this day.

Cookies created by the website you are actually visiting are known as ‘first party cookies’.

These are useful for things like keeping you logged in, remembering your site preferences, and shopping.

The problem with cookies comes when third parties like advertisers use them to gather data on people without their express knowledge or consent.

Digital advertisers have long used cookies to make ads on websites ‘relevant’ to you. Cookies are the reason you get haunted by shoe ads in the week after shopping around for a new pair of Nikes.

Suppose your favourite online store is ReallyCheapThings.com.au. When you landed on the site in search of bargain Nikes, not only did ReallyCheapThings.com.au create cookies on your computer, but so did its advertising partners.

These third-party cookies get passed around and analysed so that when you visit another site – such as a blog or news website – its advertising partners cross-reference your cookies and bombard you with ads for shoes.

Clearing cookies

Because cookies are stored locally, you can see this in action.

First clear your browser cookies – but beware! This will log you out of most sites.

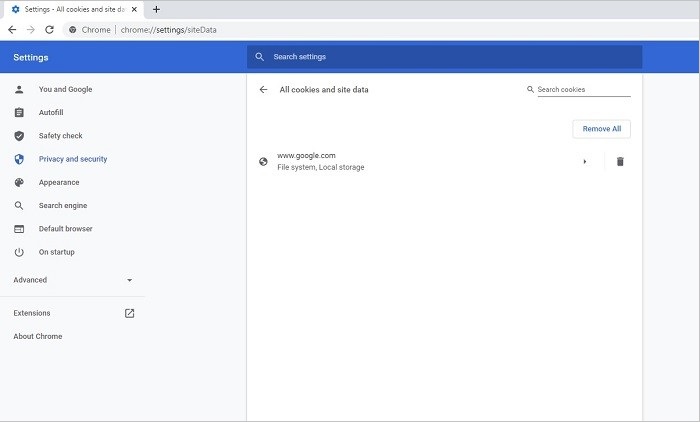

On Google Chrome, these settings can be found at this link or by clicking the three vertical dots in the browser’s top right corner, navigating down to ‘Settings’, and selecting ‘Privacy and Security’.

After you have cleared your cookies, make sure ‘Allow all cookies’ is enabled.

Here’s what an empty cookies folder looks like in Chrome:

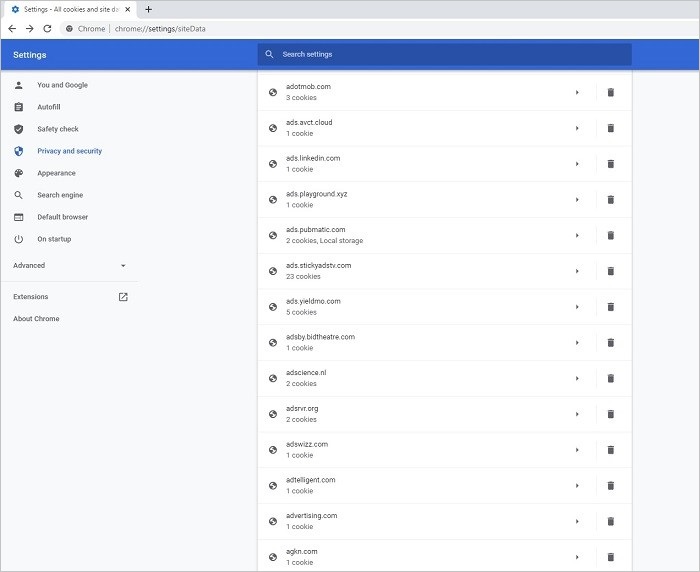

And here’s what that cookies folder looks like after 10 minutes of day-to-day browsing with third party cookies enabled:

Thankfully you now have more options for controlling who uses your cookies.

Google Chrome has an option to disable third-party cookies in the ‘Privacy and Security’ section of browser settings, as does Microsoft Edge.

In fact, Google is planning to phase out third-party cookies in favour of its Privacy Sandbox – a system that logs browser activity and lumps users into large groups for advertising, rather targeting individual interests.

Regulators are already looking into whether the tech giant’s proposals will inherently favour its own ads services over other companies’.

Fingerprinters and trackers

Third party cookies are only part of the way your everyday internet browsing is used to monitor you and sell advertisements.

Many web pages incorporate other forms of tracking and fingerprinting – technologies designed to identify users based unique features such as their device, location, and software configuration.

By combining different metrics, services can follow you around the internet without needing cookies.

Tools like the browser extension uBlock Origin block trackers disabling the code of known tracking processes from web pages before they load.

An open source extension, uBlock Origin leverages community-updated public lists of web processes that it filters out and makes your browsing a little more private.

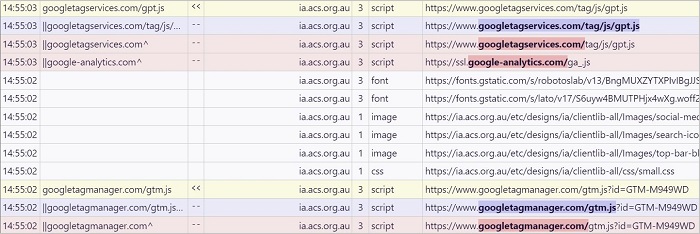

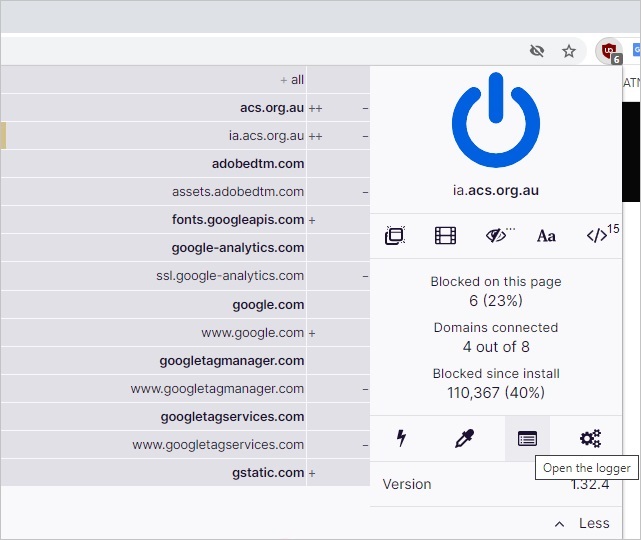

To help its users understand and debug the extension, uBlock Origin features a unified logger you can use to better see behind what founder Raymond Hill calls the “privacy-invading apparatus” that enters your web browser on most sites.

View the uBlock Origin logger by opening the uBlock Origin extension and clicking the small window above the version number.

With this window open you can see things like the Google Analytics scripts sitting behind the Information Age front page that we use in order to know things like how many people visit individual stories each week.

Click on an article and you will see uBlock Origin filter trackers that are part of other features on Information Age like social media sharing buttons and comment moderation service Disqus which those platforms use to track their users across the web.

Head to a monetised news site like News.com.au or The Guardian and uBlock Origin’s logger will show you various scripts and beacons used to track their readers and deliver advertising campaigns.

While not expressly designed as an ad-blocker, uBlock Origin does also tend to remove ads as an added bonus.

Privacy browsers

Since uBlock Origin is maintained by one person who refuses to receive donations, there’s no way of knowing how long it will remain as a useful blocking tool.

Thankfully, there are all-in-one privacy-focused browsers that disable known trackers and third-party cookies by default.

Mozilla Firefox is arguably the most well-established privacy browser.

Owned and operated by the non-profit Mozilla Foundation, Firefox is designed as a simple way to let people access the internet without having their data mined.

Another slightly more complex privacy-focused browser is the Tor Browser which is also run by a non-profit, the Tor Project.

Like Firefox, Tor keeps third-party cookies away and blocks common tracking processes but it also aims to limit fingerprinting by making all Tor users appear exactly the same, regardless of location, hardware, or software configuration.

It also natively supports the Tor network that uses different relays to hide obfuscate traffic. More on that next week.

Finally there’s Brave – a browser that cookies, ad tracking, can run on the Tor network, and also features an alternative economic model for the internet.

Brave blocks native advertisements and lets users opt-in to receive advertisements in the form of occasional pop-ups.

As a reward for viewing ads, users receive Brave Attention Tokens which they can pay forward to participating content producers, trade into crypto or fiat currencies, or hold in their wallets.

In Part II: Metadata, VPNs and Tor.