The opening of NEXTDC’s $1.5 billion M3 data centre complex in Melbourne’s West Footscray significantly boosted Australia’s sovereign data centre capacity – even as, just 2km away, recent record flooding continued to destroy businesses and homes with impunity.

And while the forces of digital transformation have pushed many large businesses to move their critical applications and services into M3 and similar facilities – NEXTDC already manages data centres used to provide services by over 770 companies including Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Salesforce, and others – the majority of smaller businesses still run their key applications from systems running within their business premises.

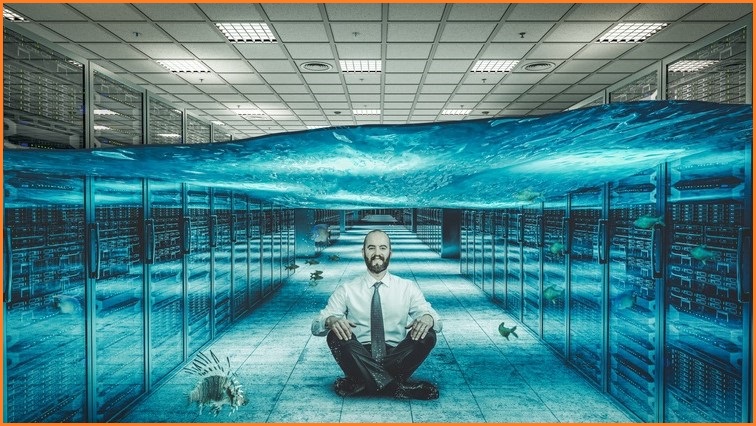

When those premises are suddenly covered by a metre of water, service interruption is inevitable and the risk of permanent data loss is real – threatening damages much higher than government support can cover.

Yet with Internet services and business infrastructure being rapidly concentrated into facilities like M3, the consequences of a flood or other natural disaster would be amplified manifold – and that is why NEXTDC managing director Craig Scroggie remains confident that early flood modelling efforts will keep the facility’s feet dry despite the depredations of the nearby Maribyrnong River.

“Site selection for data centres is critically important, and we have to ensure that sites are protected from any sort of floodplains, flight path, bushfire zone – they’re all things that have to be avoided when we design mission critical facilities,” Scroggie told Information Age.

Yet with this year’s floods setting records, how do data centre planners build in enough of a buffer zone to ensure that a perfect storm couldn’t send waters perilously close to key facilities, or even inside it?

“When we look for a site, it has to be flood-free,” Scroggie explained.

“We generally look for a 1 in 100 or 1 in 500-year flood resiliency, then build the site above the highest level that would be estimated in the event of overland flow.”

“Many great locations that we find might have fantastic power, be close to the city, have convenient access to freeways – but if they could be flood affected, we can’t choose them.”

Yet staying high enough to avoid flooding is only part of the resilience exercise: with many telecommunications companies, energy providers, rescue organisations, and government support services now running from major data centres, continuity of service becomes even more critical during times of crisis.

In laying out plans for the 150MW M3 facility, which consumes enough electricity to power 100,000 homes, engineers added enough backup generators – the site has capacity for more than 500,000L of diesel and water – to ensure that it would continue running even if the power grid were down and flood waters had cut off road access to the facility.

“We know exactly where the water would get to even in the most extreme event,” Scroggie said, “and we build to plan for managing to continue to operate during those circumstances, so those sites are always available.”

“We have a 100 per cent uptime guarantee, so even in those types of extraordinary circumstances, the facility would not be impacted.”

The power of choice – and the challenges of having none

With data centres now recognised as critical infrastructure by the government, their continuous availability has become a matter of national security and operational continuity.

For those small businesses that don’t have the luxury of changing their location, however, natural disasters can be cataclysmic – forcing years of hard recovery for operators that may not have the resources to recover their core systems and data.

Crowdfunding site GoFundMe, for one, has been overwhelmed with requests for help for business operators in flood-hit areas like Lismore, Moree, and Maribyrnong.

Other organisations in such areas are thanking their earlier decisions to move data and applications into remote cloud facilities.

Although higher-than-expected floods may devastate physical assets and capital equipment, continuity of core services at least means such businesses can continue operating from temporary premises while the physical damage is addressed.

Regional university campuses in flood-prone areas, like Southern Cross University’s Lismore site and University of Western Sydney’s Hawkesbury campus in Richmond – and even the University of Queensland’s urban St Lucia campus just south of Brisbane – are often tucked into river bends where floodplains satisfy their need for space.

That means they need to be ready for the inevitable flooding that can cut them off from surrounding areas – just one of several reasons why universities have been leading the charge to move once-onsite data centres into hosted facilities.

“That space can be better used for other purposes,” said Daniel Saffioti, a consultant who spent years as a university CIO and oversaw the centralisation of core IT services into facilities similar to M3.

“It’s really hard to run a modern-day data centre,” he told Information Age, “and public cloud hosted services give you a lot of inherent redundancy and scalability”.

“If you push your learning management system to public infrastructure, for example, then issues around scalability become a matter for the provider,” Saffioti said.

“You really want to avoid building on premises if you can avoid it.”