Customers of neobank Volt have one week to withdraw over $113m in deposits after the once-buoyant challenger bank announced it is shutting down after falling victim to the one-two punch of the pandemic and the current “challenging” economic climate.

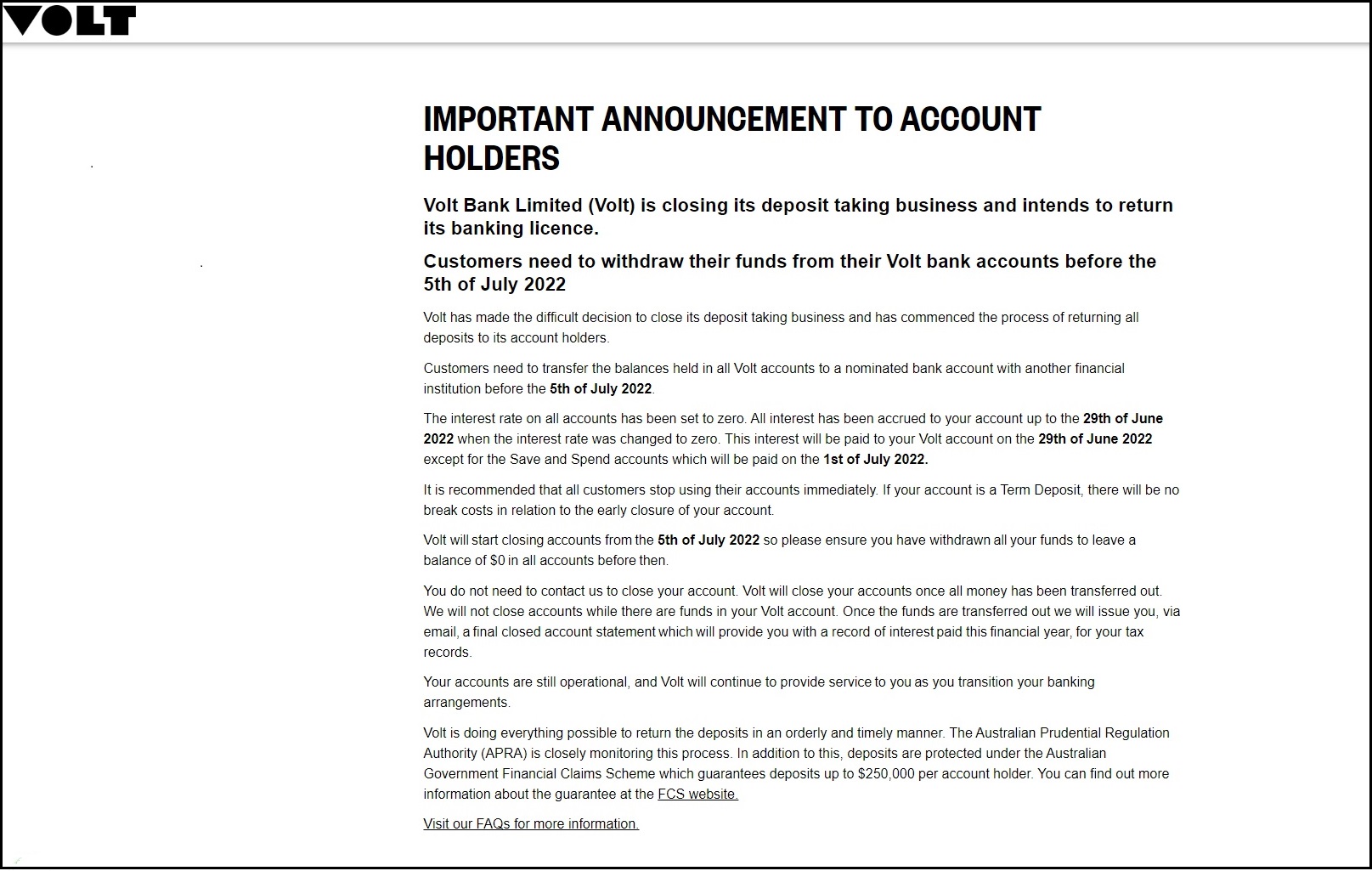

“Volt is doing everything possible to return the deposits in an orderly and timely manner,” the company announced while explaining that the difficult economic climate meant the company’s board had decided it was “unable to secure the funding needed to continue.”

The company will sell its mortgage portfolio and more than 6,000 account holders are being instructed to transfer their Volt balances to “another financial institution” before Tuesday, 5 July.

Interest has been frozen as of 29 June, with the company noting that the process is being monitored by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) and that it “has adequate funds and liquidity to support the return of deposits in full.”

“In reaching this difficult decision we have considered all options,” the disappointed Volt CEO Steve Weston said in announcing the shutdown, “but ultimately we have made this call in the best interest of our customers.”

The move comes just over three years after Volt was awarded a full authorised deposit-taking institution (ADI) license by APRA, leveraging the cloud-based Temenos banking platform to take on larger competitors with an extensible core banking system.

That system helped the company strike an innovative partnership to provide banking services to cryptocurrency exchange BTC Markets late last year in a move that was meant to help it tap the exploding market for cryptocurrency exchange and transactions.

Yet despite Volt’s optimism, the pandemic’s financial disruption ultimately proved too much for a company whose deposit base was a rounding error compared to its larger competitors, who manage the lion’s share of the more than $5.7 trillion currently deposited in Australian ADIs.

This liquidity crunch limited the company’s ability to maintain operations, threatening its ability to meet APRA’s capital buffer requirements and compromising profitability due to the challenges of the current economic climate – which has seen APRA prioritising capital adequacy as a key enforcement priority.

End of an era

Similar issues may well await many of the estimated 400 other neobanks around the world – nearly all of which, according to a recent Simon-Kucher & Partners analysis, are struggling to achieve profitability.

Despite having nearly 1 billion clients worldwide, less than 5 per cent of neobanks have reached breakeven, the analysis found, noting that “neobanks’ impressive growth and valuation numbers haven’t yet widely translated into profitability…certain segments and markets are providing more fertile ground than others.”

And while Australia’s neobank industry was singled out as “developing quickly” with “large ambitions”, the firm noted that sector – where new contenders courted disaffected big-banking customers with no-frills mobile and online banking and promises of higher interest rates – had already had “quite a dramatic and turbulent ride.”

“Known as a breeding ground for innovation,” Simon-Kucher’s analysis notes, “we expect the second wave of neobanking in Australia to set standards for cutting-edge banking propositions.”

Just what those propositions will be, however, remains to be seen since several potentially disruptive business models have now been rendered unsustainable.

The announcement on the Volt website. Photo: supplied

Chastened by market reality, one-time Volt competitor Xinja backed away from high-interest accounts and wound up its operations at the end of 2020 after burning through its funding and failing to find additional backing.

Small business-focused Judo Bank has seen more success targeting its niche amidst defensive volleys by big-banking rivals – the NAB, for one, purchased neobank 86400 – that have interpreted the neobank wave as a cue to improve their own services.

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia’s strategy of “building tomorrow’s bank today… is leading the recovery by investing in digital experiences,” Timothy Roberts, executive manager digitisation with the CBA, said during a recent webinar that read like a neobank laundry list.

“This involves differentiating our proposition [by] integrating digital experiences end-to-end with world-class engineering for operational excellence…. Digitising and scaling our processes for growth through automation are key to this strategy.”

With its digital-only design seeming to have inspired its rivals rather than beaten them, Volt’s decision to cut its losses leaves Australia’s neobank sector without the critical mass that was supposed to help reinvent the way Australians bank.

And while the “highly fragmented” neobank market still harbours considerable innovative spirit, its future disruptive power remains to be seen, Gartner analyst and vice president Vittorio D’Orazio noted during a recent appraisal of neobanks as standard-bearers of fintech disruption.

“Fintechs are highly fragmented… and part of the economy of intangibles,” he said. “They sell intangibles and sell services, and they don’t have much in tangible assets… they actually are virtual organisations sometimes.”

And while a single fintech may be a “small and impressive organisation,” he said, “a single fintech is not really dangerous…. However, when we consider a swarm of fintechs, the situation changes dramatically.”