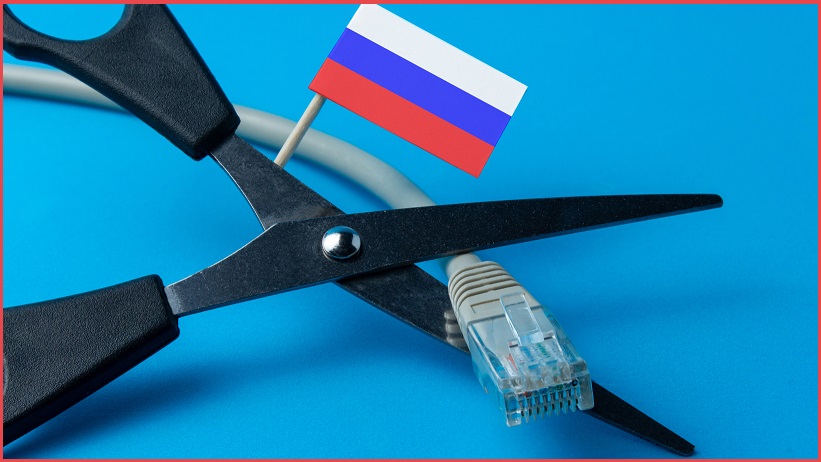

More than 114 million Internet users in Russia may be disconnected from the global Internet within days, with reports suggesting the country’s government will use technical measures to block its population from foreign reporting about its invasion of Ukraine.

Reports suggest Russia is now transitioning Internet service providers to state-controlled DNS (domain name service) servers, enabling government regulator Roskomnadzor to explicitly ban outside news, video, communication and other services.

That amounts to an information blackout for the estimated 76.9 per cent of the population that has Internet access in Russia, whose government has blocked Western information services such as Twitter and Meta-owned Facebook and Instagram.

The latter service was recently blacklisted after suspending normal content rules that would have previously banned users who called for violence against Russian President Vladimir Putin and the soldiers currently demolishing Ukraine’s civilian areas.

Yet banning those services is just the run-up to what analysts believe could be the complete disconnection of the country’s population.

Russia’s government has been preparing for such a move for years – banning virtual private networks (VPNs) and proxy services; blocking access to the Tor anonymity network used by the BBC and others; and passing a ‘sovereign Internet’ law in 2019 enabling complete disconnection that would shift the country to a Russia-only domestic Internet.

Yet while it might block consumer services, the system is unlikely to prove impenetrable, argue analysts from threat-intelligence firm Flashpoint, who note that hackers are already trading strategies for bypassing technical controls.

“Due to the infrastructure of Russia’s Internet,” the firm notes, “a ‘kill switch’ for outside Internet communication is a significant undertaking.”

“Although the Russian government claims to have already set up this infrastructure, it remains questionable whether the infrastructure would pass its first real-life test.”

The great Ural filter

Russia’s push to block access to unfiltered reporting is a deep nod to China’s long-running ‘Great Firewall of China’ – a collection of URL blockers and other technical controls that prevent Chinese citizens from accessing Western Internet services.

The Great Firewall works at low level to actively interfere with requests to outside services using a combination of blocking methods that include deep packet filtering, DNS spoofing, IP range banning, packet forging, and more.

Its pervasive interference has complicated life for outside information services like Google, which exited the Chinese market after government demands for censorship.

In 2019 Google shut down Project Dragonfly, a skunkworks project initially designed as a compromise before widespread employee protests saw it axed.

“We’ve seen forever that the Fourth Estate is a valid intel gathering target for governments with different levels of, shall we say, ability to absorb negative press,” said Alex Tilley, counter threat unit lead researcher with Secureworks, who was watching media organisations become prime targets of information warfare even before the invasion.

“Everyone’s come to understand that this is how intelligence is done in the 2020s,” Tilley said, referencing ongoing hacking and blocking campaigns such as the recent hack of News Corp attributed to the Chinese government.

“There’s a thirst for information to understand how they how their response is being viewed, and who is talking to journalists about what they’re doing inside their country.”

“That level of understanding of what’s going on is at its highest peak now, if not during a time of war. It’s just how this is all done now.”

The success of China’s nationwide filter has had a chilling effect on freedom of expression in that country and seems to have become an aspirational goal for Russia, which has cosied up to its increasingly uncomfortable neighbour and this week asked China to provide military and economic assistance.

Just as the government of Iran also orchestrated a nationwide shutdown of Internet services, blocks on popular content-sharing services will support Russia’s propaganda machine by letting it control the public narrative around its systematic annihilation of Ukrainian civilians.

Yet whether Russia can completely disconnect from the world remain to be seen, Flashpoint analysts warn: “While Russian domestic technology firms can make some restrictions possible,” they concluded, “claims that the Kremlin can ‘flip a switch’ and isolate their population from the Internet are mostly propaganda.”

“Unlike Iran or China, which built a disconnected Internet infrastructure much earlier, the scale of the task for Russia is enormous and requires immense coordination…. It is presently unclear whether Russia meets the technical conditions for an effective disconnection.”