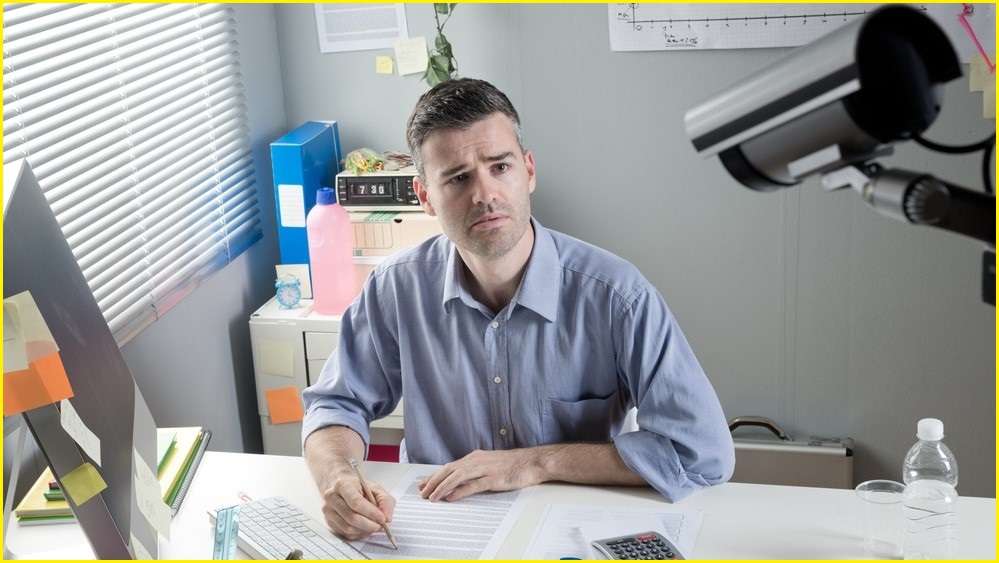

Outdated laws are allowing “unchecked and unchallenged” employers unfettered use of surveillance and automation technologies that are leaving employees stressed and sidelined, a NSW Parliamentary committee has warned in advocating for a legal update.

The newly published second and final report of the Select Committee on the Impact of Technological and Other Change on the Future of Work and Workers in NSW – which was briefed in March 2020 and published its first report in April – made 13 recommendations to overhaul workplace surveillance and automation legislation that was originally published in 2005.

The NSW Workplace Surveillance Act 2005 should, the committee found, be updated to reflect advancements in technology over a 17-year period that has seen the development of smartphones, high-speed wireless networking, connected security cameras, AI-driven employee monitoring, and other technologies.

The laws should be amended to require external approval before employers implement surveillance measures include “clear” privacy protections for workers, and the improvement of notification requirements so employees have the opportunity “negotiate and oppose proposed surveillance activities,” the committee recommended.

Such changes should also give workers the right to refuse “excessive or unreasonable workloads or intrusions into personal or family time,” as well as allowing them to “disconnect from work devices” or the obligation to respond to work communications outside of work hours.

The inquiry also recommended the creation of best-practice guides around workplace surveillance and automation, and advised the NSW Government to develop a formal strategy for managing technological advancement in state public sector agencies.

“Technological advancement is rapidly expanding workplace surveillance and the automation of work,” said Committee chair Daniel Mookhey, warning that “employers, motivated by bottom lines, are unchecked and unchallenged in their use of these tools, reaping the benefits that flow.”

“Laws have not kept track with the many, many ways that technology enables workers to be monitored, often without them being aware of it,” Mookhey said.

“Employees, stressed by constant monitoring, lack adequate protections, are sidelined in the process, and do not share in the benefits.”

Coming to terms with progress

Whether driven by the desire to improve operational efficiencies – or to compensate for chronic and problematic shortages of skilled individuals – adoption of process automation technology is increasing at breakneck pace.

Spending on robotic process automation (RPA) tools, for example, grew by 31 per cent last year and is projected to add another 19.5 per cent this year, Gartner has projected, as companies embrace automation for everything from large-scale document processing to warehousing and package sorting.

“Organisations are leveraging RPA to accelerate business process automation initiatives and digital transformation plans,” said Gartner distinguished VP analyst Cathy Tornbohm, “linking their legacy nightmares to their digital dreams to improve operational efficiency.”

Yet employees risk becoming collateral damage in the push to automate the enterprise, with increasingly intrusive surveillance and efficiency monitoring technologies raising hackles amongst workers’ rights advocates, even as many companies try to impose workplace surveillance technologies to keep tabs on work-from-home employees.

A recent ExpressVPN survey of workforce surveillance practices found that 78 per cent of employers admitted using employee monitoring software to track employee performance or activity, with 73 per cent saying that recorded calls, emails, or messages “have informed an employee’s performance reviews” and 46 per cent saying they had terminated an employee based on data collected during surveillance.

Although many employers have embraced surveillance, a recent Harvard Business Review study found that employees are likely to intentionally stymie surveillance measures by taking unapproved breaks, disregarding instructions, damaging workplace property, stealing office equipment, and ‘quiet quitting’ as they intentionally slow down their pace of work.

Such outcomes are inevitable when employers embrace “nightmarish” surveillance technologies, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) senior policy analyst Jay Stanley recently warned, pointing to surveillance-heavy China as a worst-case scenario where “there is no space between what can be done, and what is done.”

Local thinktank the Australia Institute has been equally concerned, launching its Centre for Responsible Technology (CRT) in 2019 with a key focus on what CRT director Peter Lewis recently described to the Select Committee as “the unregulated intensification of surveillance in the workplace”.

The Committee’s recommendations are targeted at clarifying the space between those two extremes – with the government’s response expected by February and the new final report hoped to spur what Mookhey called “proactive, deliberate and creative interventions… to better shape the future of work in NSW.”

“Workplaces today are vastly different to what they once were,” he said.

“We cannot leave the fate of our workplaces and indeed the labour market in the hands of tech companies.”