‘Back in My Day’ is an Information Age series profiling some of our older ACS members and Information Age readers speaking about their early days in IT.

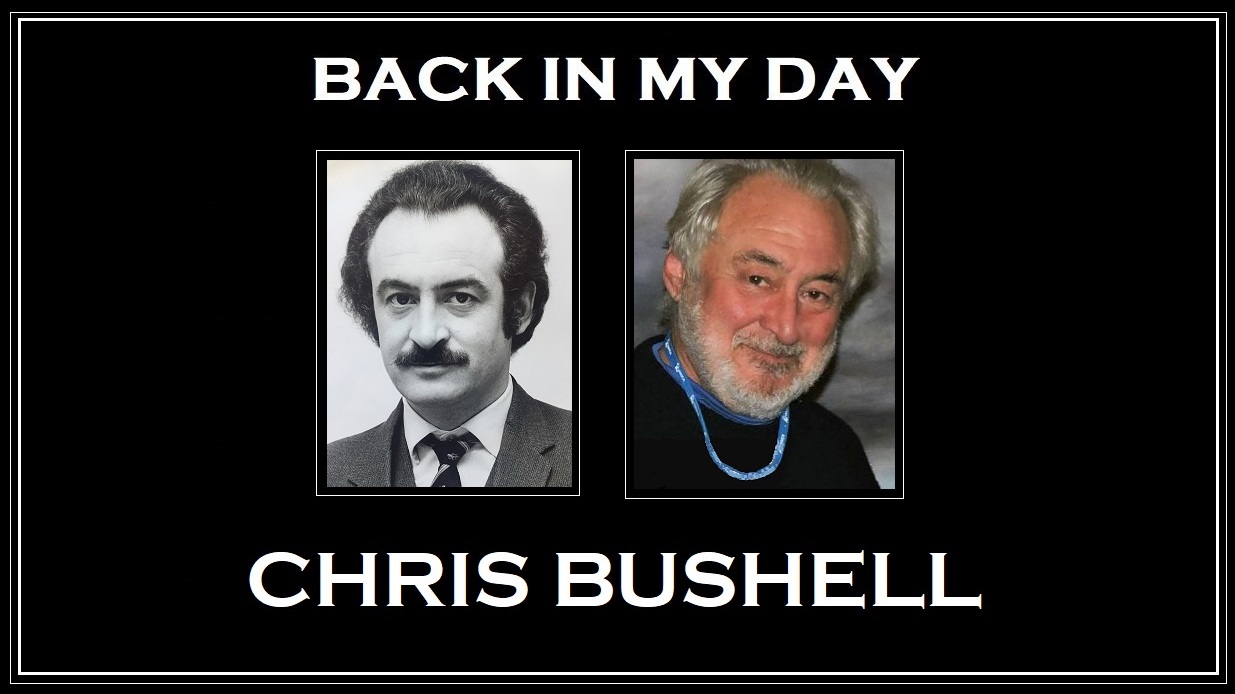

This week we speak with Chris Bushell, aged 78, from Adelaide, South Australia.

How did you start working in tech?

I studied maths at Manchester University – I was born in West London. I did a numerical maths course and came across the computer. I was sending programs to it, and that fascinated me. I applied for jobs and got offered all of them.

I went to work at ICL, my very first job was writing operating systems. That was a hell of a thing to start with. It was good fun, and there were some people who were very erudite. They were good fun to work with.

We were writing in essentially machine language. We were trying to work out what an operating system should do – nobody had written them before. At the time all we had were magnetic tapes, we didn’t have discs or anything.

The machines we worked on were 16KB. In this machine, we had to fit an operating system and programs to run on it. It was a shoehorn job.

Was there any sense at the time that you were at the very early stages of something so important?

On the one hand, absolutely.

But on the other hand, I remember thinking in the early stages, we didn’t have any video screens when we started, and we watched Get Smart with the telephone in a shoe, and I thought maybe we’ll get to that and if we did it’d be expensive.

But when we did get there, it was free.

I had no idea really. If you’d told me that bottled water was going to be one of the biggest businesses when I got older…you can’t tell what’s going to happen.

Where did you go after ICL?

I had heard that an enterprising salesman in Adelaide had sold a machine to the Institute of Technology that was far bigger than they needed on the understanding that ICL would set up a software house there.

But he hadn’t told anyone yet.

My partner was from Australia, from Melbourne, and she got wind of it before anyone else in London did.

By the time the message went up, the salesforce on one side and down to the technical side, we’d already talked to the managers, and we said we’d go set it up.

That was when I was at the ripe old age of 27 years old, and I went to set up a software house in Adelaide.

How did that go?

We basically arrived in the middle of a heat wave in January 1970. We were supported by the salespeople who’d never met any serious software writers before.

They set us up at Mawson Lakes in Adelaide, inside the Institute of Technology. We built the thing up over three years to about 60-odd people. Then the company wanted out.

So, I got a job at the Institute of Technology as a lecturer straight off. That was in a subject I didn’t have any qualification in. We really were the guardians of the emperor’s new clothes. And we did know it.

What have some of your career highlights been?

It would have to be the people I taught while at the Institute of Technology. I didn’t really teach programming – I taught systems analysis, which is basically problem-solving. That was one of the things in my life which was really useful.

A lot of the students were older than me at that stage, there were a lot of mature age people who were public servants. I’m still friends with some of them.

What was working in tech in Australia like compared to the UK?

You didn’t get paid as much in England as you did in Australia. And when I got to Australia I knew more than the people here which was also, to be honest, made it more fun.

Did you ever have any difficulty in getting a job?

I feel sorry for people these days. I never failed to get a job I applied for. To be honest, after I left the Institute of Technology, I didn’t apply for a job. I was just offered jobs.

What advice would you have for someone just getting started in the tech sector, or considering going into it?

I’d say to them, do it if it’s what turns you on. People should only do what they want to do. I used to go to careers night at the Institute of Technology, and people used to come in and say, ‘I want my son or daughter to study computing because that’s the new thing’.

But we should let them make up their own mind about what they want to do. If people want to, it’s a hell of a lot of fun working with computers.

When I started writing an operating system, I said, ‘what language are we going to use?’. They said they hadn’t really decided the language yet, they hadn’t got a compiler for the language and there was no editing system because they hadn’t got a compiler to run the programs.

We got to make it all up as we went along.

What have you loved about working in tech?

Part of it is about knowing things that nobody else did, if I’m honest about it.

What was it like working at Computer Sciences Corporation?

I got to a point of saying, ‘you tell me a fixed job you want me to do, and I’ll do it. Whether it was a three-month contract or whatever, and the rest of the time I’ll take off’.

That suited me fairly well for a couple of years. And at the age of 50 I said, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore’, so I retired, much to everyone’s disgust.

I went and managed ski clubs for a ski season.

What are you up to now?

I’ve really enjoyed everything I’ve done since I retired, the walking and the hiking. I build walking trails now. We have built the longest walking trail in South Australia, entirely by volunteers. It’s 325km long, and goes from the Murray Bridge to Clare.

That took 21 years to do.

We finished it about four years ago and we had a great celebration in Clare, all the local pollies were there.

We’re now maintaining that, and we’ve just done a cyclist trail. We maintain that trail and we regard it as a spine, and we’re building bits on it.