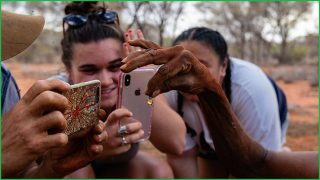

First Nations people living in remote communities have the worst internet access in the country thanks to limited infrastructure and a lack of digital training, which all points to a possible failure for the government to meet its Closing the Gap targets.

The latest Australian Digital Inclusion Index found Australians living in remote First Nations communities are “among the most digitally excluded Australians” – far more than their non-First Nations counterparts.

Out of a total digital inclusion score of 100, the national average for First Nations people is 65.9 compared to an average of 73.4 for Australians overall.

In major cities the gap between First Nations and non-First Nations digital inclusion is small (just 1.7 points) but in remote Australia it balloons to over 24 points.

Dot West, chair of the First Nations Digital Inclusion Advisory Group, said the results show a need for change.

“Digital inclusion enables individuals to seek, receive and impart knowledge and ideas of all kinds, it vastly expands an individual and communities’ capacity to enjoy their human rights: from education, health care, freedom of expression, economic, social and political development,” she said.

“The internet has become an indispensable tool for millions of Australians, something many take for granted.

“But for First Nations communities, it can be a powerful tool in combating inequality, accelerating development and progress for First Nations individuals and the community as a whole.”

Under the national Closing the Gap agreement, the government has a target to create “equal levels of digital inclusion” for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by 2026.

Access is the single biggest gap in remote communities, the Digital Inclusion Index found, pointing to “limited telecommunications infrastructure” as the primary problem.

But it also notes a preference for pre-paid mobile services in remote First Nations communities which tend to be more expensive per gigabyte than post-paid plans but provide greater control over cost.

Alarmingly, 53 per cent of First Nations people said they had opted to go without food or paying other bills in order to stay connected to the internet.

Communications Minister Michelle Rowland said the report made makes it “clear that more needs to be done to improve First Nations inclusion”.

“A key focus of the Albanese Government is extending the opportunities that come from being online to more Australians,” she said.

“That’s why our Better Connectivity Plan is delivering the single greatest investment in regional communications since the inception of the NBN.”

May’s budget set aside $656 million over the next five years to improve mobile and broadband access in regional Australia with the bulk of it going toward mobile coverage in regional roads.

Of that money, $200 million is earmarked for the Regional Connectivity Program which has previously funded Telstra mobile base stations, fixed wireless, and limited fibre projects in the regions.