After two years of consultation, the government released its First Nations Digital Inclusion Plan on Sunday with the optimistic goal of reaching its Closing the Gap target of equal levels of digital inclusion for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by 2026.

The plan comprises a framework centred on access, affordability, and digital – the same areas measured by the Australian Digital Inclusion Index – alongside a list of existing and planned actions from state and federal governments, business, and the non-profit sector. It also has a broad set of ‘priorities for further work’.

Minister for Indigenous Australians, Linda Burney, said it was important for all Australians to be able to access and use digital technologies.

“In a world where the technology landscape is rapidly changing to provide greater opportunities to connect with each other, the economy and so much more, I’m so pleased that this Government is committed to ensure our First Nations people aren’t left behind,” she said.

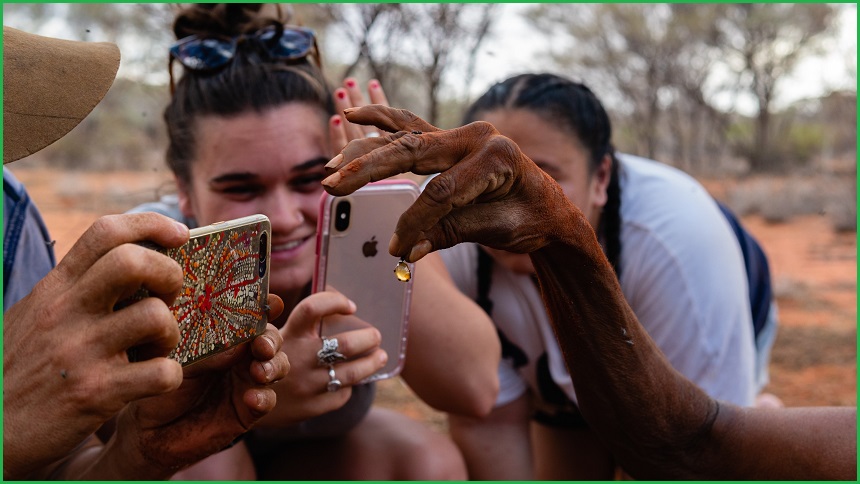

“Strengthening digital inclusion for First Nations people, especially if they live in regional or remote Australia, provides significant opportunities for increased connections to community, country and cultural identity.”

According to the latest Digital Inclusion Index, First Nations people continue to face high levels of digital exclusion – especially in remote communities where there is a serious gap between Aboriginal people and the rest of the population.

As the plan points out, access to digital technologies “is fundamental to the economic, social, and environmental wellbeing of First Nations people”.

While a move toward online service delivery – especially in health and education – has created a greater opportunity for communities separated by space, the lower levels of digital access can make it even harder to use services, thus exacerbating disadvantage.

Communications Minister Michelle Rowland said connectivity was particularly important for people in communities “where the tyranny of distance has the greatest impact”, adding that her government wanted to “ensure that no one is left behind”.

What’s the plan?

The National Indigenous Australians Agency identified that future actions need to involve partnerships with First Nations people and communities, they have to be ‘place-based’ and localised to tailor the needs of specific communities, they need to be fit for purpose, and they should involve co-ordination between the Commonwealth, states and territories, non-government organisations, and business.

Most of the 167 existing initiatives mentioned in the plan are generalised for the broader Australian population, and there are only 21 planned, or ‘pipeline’, activities which shows the need for a more cohesive and direct approach to improving First Nations digital inclusion.

The government’s current communications centrepiece is its Better Connectivity Plan, under which sits the Regional Connectivity Program.

That program has already funded two rounds of grants worth more than $250 million.

Only around 10 per cent of that money has gone to projects that directly mention improving telecommunications infrastructure for Aboriginal or Indigenous communities, but the government has said the program’s upcoming round will see $25 million dedicated to First Nations communities.

The biggest single beneficiary of the Regional Connectivity Program has been Telstra which pulled in over $108 million for mobile base stations in regional or remote parts of Australia.

In 2021, Telstra was fined $50 million for its “unconscionable” sales conduct after representatives sold expensive mobile plans to people who couldn’t afford them and racked up debts as high as $19,000.

Aboriginal people in remote parts of Australia tend to be mobile-only internet users and are more likely to use pre-paid plans out of economic prudence, the First Nations Digital Inclusion Plan mentions.

But pre-paid plans tend to be more expensive per gigabyte and mobile service generally doesn’t offer the uncapped data use you will find with home broadband.

Barrier to Country

A recent Queensland University of Technology research program outlined the difficulties, and importance, of online connectivity on Mornington Island where 80 per cent of the community is Aboriginal.

It noted that a “lack of mobile coverage on traditional homelands” was seen as “a barrier to engagement in activities on Country”, effectively limiting the desire for young people to venture far from town.

Telstra is the only mobile network on the island and its 4G reaches just “one-fifth of Mornington Island”, the research paper says although the island is slated for a $2.6 million upgrade as part of the Regional Connectivity Program.

Increasing the amount of infrastructure is naturally an important step in improving digital inclusion, but just the existence of mobile towers or satellite receivers isn’t enough.

Despite residents being eligible for NBN’s Sky Muster offering, the researchers said they hardly heard of any homes that were joined up to the service.

In part this is a result of the lock-in nature of service contracts, but also that there was a lack of available technical support.

“When hardware like satellite dishes, modems and routers broke, there was often no one available to fix them,” the report found, and it could take weeks or months for a technician to arrive.