Some 12 public servants breached their obligations nearly 100 times over their involvement with Robodebt, but none will lose their jobs.

The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) on Friday released its report after a year-long investigation into Robodebt, finding that public officials at the highest level had breached the APS code in overseeing the unlawful scheme.

The two department secretaries who oversaw the scheme were publicly named by the commission and found to have breached the APS code multiple times, while the other current and former public servants were left anonymous.

Despite the damning findings, the two former secretaries and other officials no longer in the public service cannot be punished, while those that remain have been demoted or fined but have kept their jobs.

Robodebt was an automated debt recovery scheme initiated by the former Coalition government.

It relied on averaging yearly income data from the ATO with fortnightly income data reported by welfare recipients.

If a discrepancy was identified, an automatic “please explain” notice was sent to the welfare recipient.

About 526,000 people received a debt notice under the scheme, which was eventually revealed to be flawed and in contravention of the Social Security Act.

The federal government eventually settled a class action lawsuit over the scheme for $1.8 billion, which included the refunding of the debts and $112 million in compensation.

It also led to a Royal Commission, with the final report handed down last year and finding that Robodebt was a “costly failure of public administration, in both human and economic terms”.

‘Lost their way’

Following the Royal Commission’s findings, the APSC launched an investigation into the conduct of several public servants involved with running the Robodebt scheme.

It has now found that 12 public servants breached the APS code of conduct 97 times.

APS Commissioner Gordon de Brouwer said that Robodebt had been a “failure of government”.

“I apologise for the damage that Robodebt caused people and their families and the suffering they endured as a result,” de Brouwer said in a statement.

Some of these public officials had “lost their way and compromised their professional standards,” he said.

“These public servants lost their objectivity and, in all likelihood, drowned out the deafening and growing criticisms of the scheme to pursue an operational objective,” de Brouwer said.

“Almost all failed to challenge the status quo as concerns emerged over time.

“As a general proposition, even the most experienced public servants demonstrated an inability or unwillingness to have difficult conversations while preserving relationships within and between departments and with their ministers.”

De Brouwer said many of the public servants involved did not act ethically.

"Decisions about policy design and service delivery must be informed by what is legally and technically possible," he said.

"But this is not the end of the story. Public servants have a duty to consider whether a decision is ethically sound.

“The question cannot be confined to whether a decision is legally and technically possible but also whether it is, in fact, the right thing to do, no matter how hard that may be."

From the top

The Commission found that Kathryn Campbell, who served as secretary of the Department of Human Services from 2011 to 2017 when Robodebt was in operation, breached the APS code in relation to six overarching allegations, with each made up of two breaches, totalling 12 contraventions.

Among these breaches was a failure in 2017 to ensure that internal and external legal advice about Robodebt were sought, a failure to sufficiently respond to public criticism and whistleblower complaints, a failure to investigate legal issues raised publicly around Robodebt, and a failure to ensure her minister was fully informed of these concerns.

Campbell went on to serve as secretary of the Department of Social Services, then secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

She was later appointed in an AUKUS-related role in the Department of Defence but resigned in July 2023 following the Royal Commission findings.

Following the APSC findings, Campbell claimed she was being made a “scapegoat” for Robodebt and accused Government Services Minister Bill Shorten of politicising the issue.

Shorten quickly hit back, saying Campbell had launched a “furious tirade blaming everyone else” and that she was not a scapegoat.

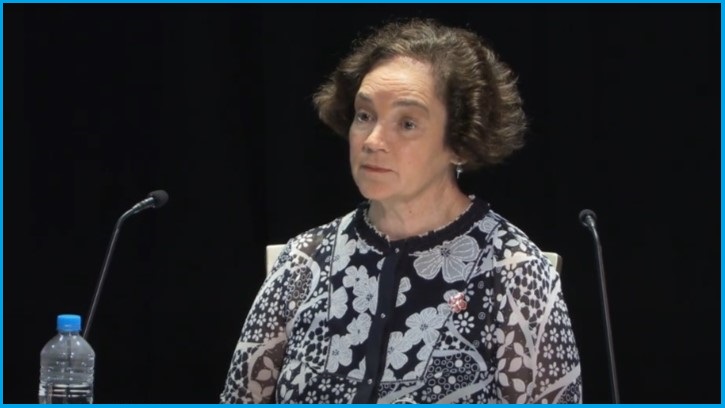

The inquiry also found that Renee Leon, who replaced Campbell in the Human Services secretary role, breached the code 13 times in relation to four overarching allegations.

These included that she misrepresented to the Commonwealth Ombudsman in March 2019 that the Department’s legal position regarding Robodebt was “not uncertain”, failed to correct or qualify representations made to the Ombudsman about this legal position following further advice, failed to ensure the Solicitor-General was “expeditiously” briefed on the unlawfulness of the scheme and failed to inform her minister of this.

Leon, who is now vice-chancellor of Charles Sturt University, responded to the findings, claiming she was fired by the former Coalition government for trying to shut down Robodebt.

“I acted as expeditiously as possible to convince a government that was wedded to the Robodebt scheme that it had to be ceased,” Leon posted on LinkedIn.

“When ministers delayed, I directed it be stopped.

“Two weeks later, my role as secretary was terminated by a government that did not welcome frank and fearless advice.”

Neither Campbell nor Leon can be punished for these breaches as neither remain in the APS, but de Brouwer said it is a “big thing” that they have been publicly named.

“It’s extremely unusual to name individuals,” he said.

“There have been people who were found to have breached the code, and they’ve been held accountable for that, and they know that they’re held accountable.”

‘Obfuscating and misleading’

The APSC found that 10 other unnamed public servants also breached their obligations a total of 72 times, including for a lack of care, diligence and integrity.

These officials also misled ministers and senior officials on the lawfulness or accuracy of Robodebt, and failed to consider the impact on and capacity of staff and work quality when setting timeframes.

These breaches range from “moderate to very serious”, the Commission’s report said.

Four of these officials are still employed in the APS and will face sanctions including demotions, reprimands and fines, but will not be let go.

The report said that one person retired before such a sanction could be handed down.

Community and Public Sector Union national secretary Melissa Donnelly said it was “incredibly disappointing” that there would be little in the way of consequences for those responsible for Robodebt.

“While the likes of Kathryn Campbell move on with their lives without sanction, our members continue to deal with the consequences of the scheme on those communities they serve and the loss of public trust,” Donnelly said.