Announcing the directive to work “primarily in an approved office”, NSW Premier Chris Minns said overseas studies showed people were less productive when working from home.

“There is a drop in mentorship. There is less of a sense of joint mission,” he said. “This is about building up a culture in the public service.”

Having examined the impacts of working from home since the pandemic started, I am not convinced.

With colleagues from the Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies at The University of Sydney Business School, I have been monitoring the changing incidence of working from home and its relationship to performance since the start of the pandemic.

Working from home means working more

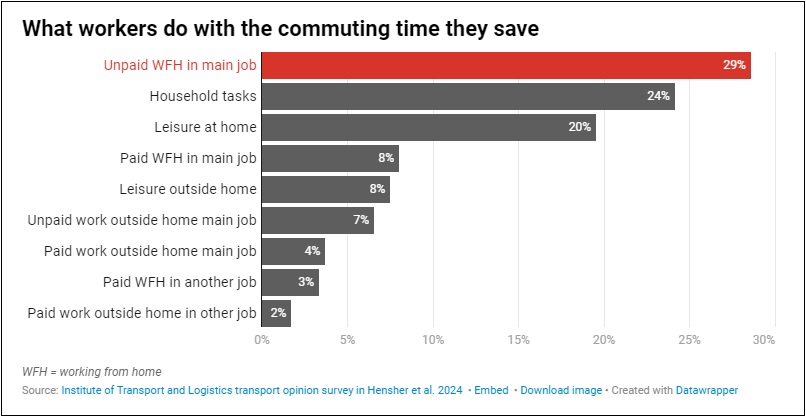

We have found that workers who take up working from home devote about one third of the time they save by not commuting to extra unpaid work.

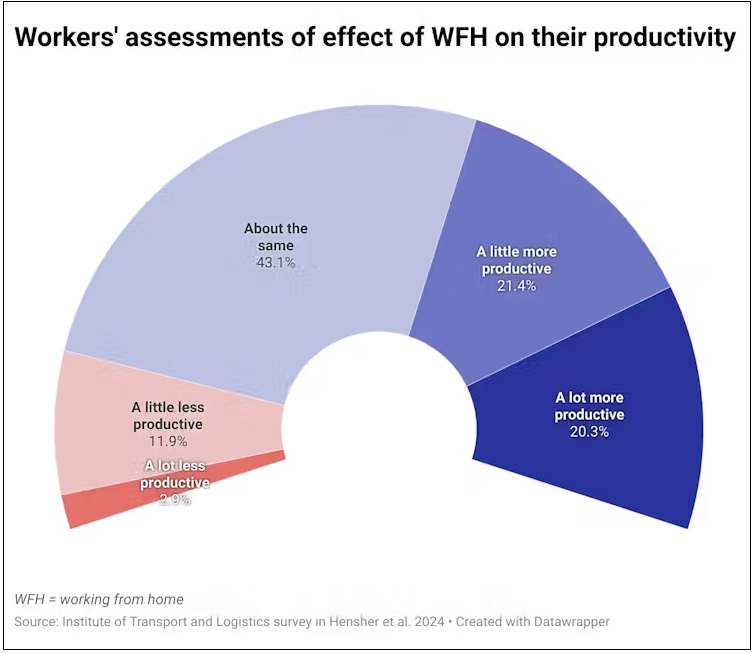

When we asked workers who took up working from home what the new arrangement had done to their productivity, more said it had improved it than made it worse.

About one in five said it had made them “a lot more productive”. Only one in 30 said it had made them “a lot less productive”.

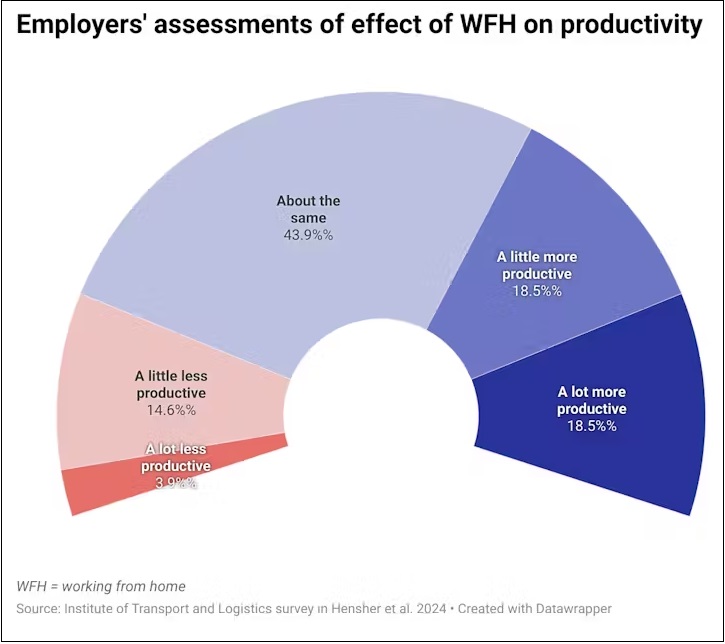

Interestingly, when employers were asked the same question about whether their workers who took up working from home had become more or less productive, the answers were about the same.

About one in five said the change had made their workers “a lot more productive”. About one in 20 said it had made them “a lot less productive”.

Our findings accord with international evidence.

A Stanford University study found that, in the United States, working from home during the pandemic had delivered a 5% increase in productivity.

It found much of the gain didn’t show up in conventional measures of productivity because they didn’t take account of the savings in commuting time.

Another study assessed the productivity of both remote and on-site call centres at Fortune 500 firms. It found working from home lifted productivity by 8%.

Another, which email metadata from North America, Europe and the Middle East, found increases in the number of meetings per person but decreases in the average length of meetings, resulting in less time spent in meetings per day.

Our own work has found some face-to-face contact is important, but two to three days per week is all that’s needed to facilitate social interaction, mentoring and sharing of ideas.

In Australia, the Productivity Commission found control over working arrangements was important to productivity.

It observed:

[…] workers may be more productive at home because they have better control over their time and enjoy better work-life balance.

And it identified better matching of workers to jobs as important.

Firms will be able to tap into a larger pool of (more productive) labour. While not strictly a productivity impact, workers have been shown to work longer hours when working from home during the pandemic.

Our research offers new evidence on what workers do with the time saved by not commuting.

According to the workers who took part in our surveys, the biggest use of that time (almost one-third of that time) was extra unpaid work for their employer.

Extra paid work took up another substantial chunk of time (whether for the main employer or not) and household tasks took up about one-quarter of the time.

The average commuting time saved by working from home in the Greater Sydney metropolitan area in September 2022 was 9.4 hours per week. This suggests the extra time devoted to extra paid and unpaid work has been substantial.

It’s important to consider this in assessments of productivity.

It would be unfortunate if the biggest effect of the return-to-the-office mandate was to make workers less generous with their time.