Quantum computing pioneer PsiQuantum has moved to quell concerns that a major new contract – to build America’s largest quantum computer – will divert resources from a similar Brisbane system into which Australia controversially invested nearly $1 billion.

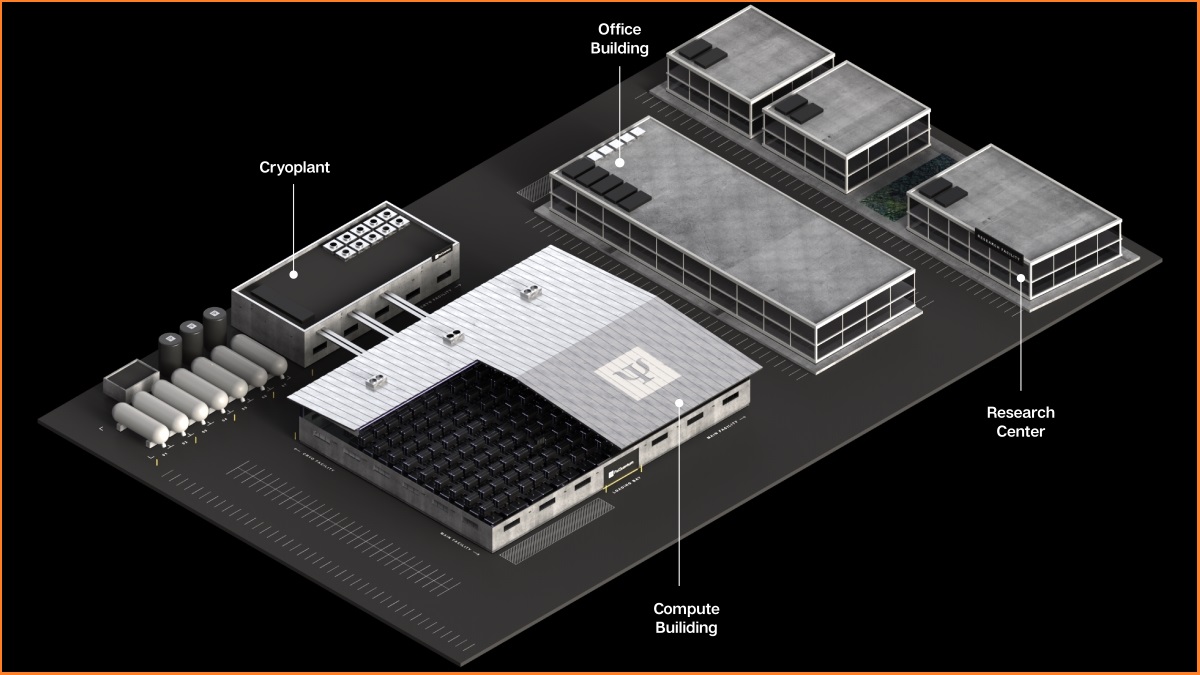

The new Quantum Computing Operations Center (QCOC), which will be hosted on a former steelworks in south Chicago in partnership with the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), will be funded with $760 million ($US500 million) from the state of Illinois, Cook County, and City of Chicago and $427 million ($280m) from DARPA.

It will be the largest quantum computing facility in the US, with the planned campus intended to house a fault-tolerant quantum computer up to 1 million qubits – the fundamental measure of quantum computing power – within the next decade.

That’s comparable to a 1 million qubit system in the works at Google; however, the innovative approach taken by PsiQuantum – whose success in building qubits from heat-tolerant photons has accelerated its mission to build “the world’s first useful quantum computer” – helped it secure $940 million in Australian government equity investments, loans and grants in a controversial tender process.

That secret tender – which will see PsiQuantum’s first utility scale quantum computer built in Brisbane under the aegis of the government’s Future Made in Australia advanced manufacturing plan – marginalised Australian quantum innovators in a process that drew Australian National Audit Office scrutiny and led critics to suggest that foreign companies were being favoured over Australian innovators despite their proven expertise in quantum computing research and commercialisation.

Spreading PsiQuantum too thin?

Whereas bits in conventional computers represent one of two states (on or off), qubits make quantum computers powerful because they can exist in many states at the same time – and leverage quantum characteristics such as the entanglement of pairs of qubits across distances.

Some critics wonder whether PsiQuantum can successfully do the same.

The announcement that US based PsiQuantum will now simultaneously build its second such quantum computer in Chicago “casts a very dark shadow” over that investment and turn the Brisbane project into a “sideshow”, Shadow Minister for Science and the Arts Paul Fletcher has said in warning that the new deal raises “obvious questions as to where the company’s real focus and energy is going to be.”

A rendering of PsiQuantum's Chicago site. Image: PsiQuantum / Supplied

Given that PsiQuantum will inevitably leverage the intellectual property rights it gains from the Brisbane project for its Chicago project, Fletcher said it seems the Australian government had failed to secure exclusivity over Australian-developed intellectual property despite giving PsiQuantum nearly $1 billion in consideration.

PsiQuantum sought to rebut those concerns, arguing that its “operations and plans in Australia remain unchanged” and that it would still commence construction in Brisbane in 2025, with the site expected to be operational in 2027 – a year before the Chicago site.

“Building and deploying these systems between strong allies is paramount to maximising quantum computing’s impact,” PsiQuantum’s Australian born CEO and co-founder Prof Jeremy O’Brien said in positioning the projects as complementary efforts that will help geopolitical allies build a “common computing environment.”

A rendering of PsiQuantum's Brisbane site. Image: PsiQuantum / Supplied

Taking a quantum leap together

For all its promises, PsiQuantum’s newest deal shifts the centre of gravity of the quantum computing industry – which the Australian government has long wanted to keep here after CSIRO projections it could be worth $6 billion and create 19,400 jobs by 2040 – across the Pacific.

Yet the move risks a ‘brain drain’ and a reallocation of financial resources that could see Australia’s quantum industry losing priority to better-resourced American ventures – and with much of the government’s quantum funding tied up in the project, the knock-on impact on other local quantum innovators could be significant.

The move comes on the heels of Microsoft’s recent decision to shut down its University of Sydney quantum computing partnership after seven years, instead returning its focus back to the US due to what the company called “organisational and workforce adjustments”.