Use of mobile phones does not cause cancer, Australian scientists have found after completing the first part of a “very reassuring” World Health Organisation-backed review that analysed 28 years’ worth of scientific research and found that even heavy phone users were not at increased risk.

Completed by a research team at the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA) – which continually investigates and sets safe exposure standards for exposure to electromagnetic and other types of radiation – the new study screened over 5,000 studies and ultimately analysed 63, which were published between 1994 and 2022 and looked at phone users in 22 countries.

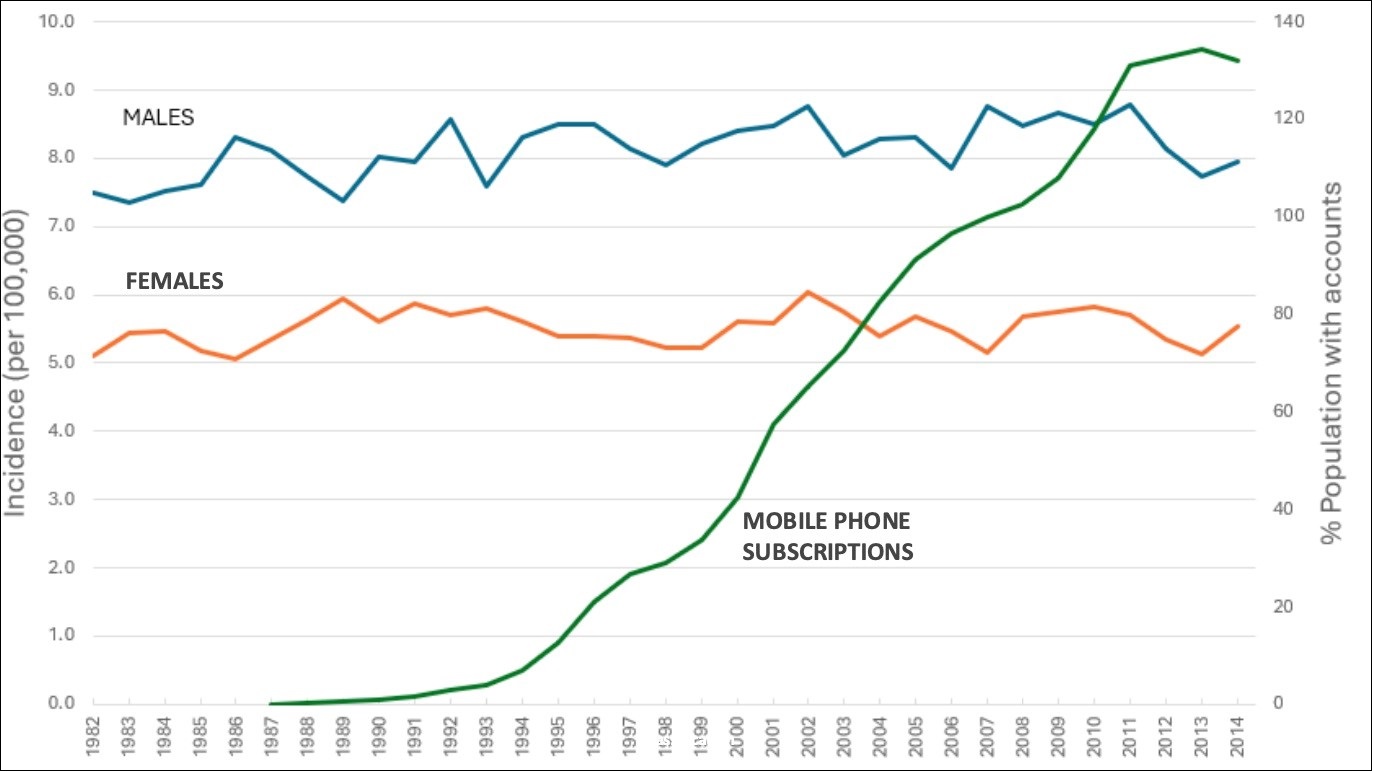

Despite surging use of mobile phones over that time – Australia now has nearly 27 million citizens and 33.59 million mobile connections – the study found that rates of diagnosis of brain cancers such as glioma, meningioma, and acoustic neuroma had not increased during the nearly three decades that the devices have been in widespread use.

There was no association with prolonged use of mobile phones, the number of phones people use, the number of calls they make, or the overall time spent on the phone.

The study also found no increase in cancer risk based on exposure from mobile phone base stations, increased exposure over time, or occupational radiofrequency exposure.

“These results are very reassuring and they’re complementary to other evidence that we’ve looked at in the past,” ARPANSA Health Impact Assessment director Associate Professor Ken Karipidis said as the new study was released.

“Even though mobile phone use has skyrocketed, brain cancer rates have remained quite stable… We believe that’s quite reassuring for a longstanding issue.”

The studies spanned all mobile communications technologies, from 1G analogue services to now ubiquitous 4G mobile broadband.

Not only was there no difference in risk between the technologies – whose nomenclature Karipidis said are marketing names that “[don’t] actually mean anything” – but as newer and more capable technologies have been rolled out “exposures have actually fallen.”

With these technologies “there tends to be a lot more base stations about, and having more base stations about actually reduces the exposure,” he explained.

“When there aren’t a lot of towers about, your mobile phone has to work a lot harder to connect to a base station that’s really far away.”

Mobile phones, he said, emit 500,000 times less radiation than the Australian standard for safe exposure to electromagnetic sources, called RPS S-1 and last updated by ARPANSA in 2021.

By point of comparison, WiFi is 100 million times lower than the standard, which itself is 50 times lower than the levels necessary to cause health effects.

Source: ARPANSA

Putting conspiracy theorists out of business

The new review – which will soon be followed by a second part examining the association of mobile phones with systemic cancers such as leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma – was commissioned by the WHO in 2019 to help establish a consensus about the health impacts of mobile phone use.

That consensus was challenged in 2013, when the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified electromagnetic radio wave exposure as a “possible carcinogen” to humans – empowering critics, prompting official advice for reducing exposure, and spawning a cottage industry of anti-radiation headphones, cases and chips designed to filter supposedly harmful radiation.

Submissions to a 2019 Australian government inquiry attracted a cavalcade of complaints, including allegations that ARPANSA “lack critical expertise” and that the Australian public was being treated as “non-consenting, uninformed subjects of a mass scale experiment called 5G.”

In 2020, hysterical Britons torched 5G mobile towers as escalating fear about the coronavirus pandemic spawned a flood of what one government official called “dangerous nonsense” and 5G became a target despite there being no evidence it was harmful.

Newer 5G technologies haven’t been around for long enough for researchers to complete similar cohort studies, Karipidis said, noting that “5G uses higher frequencies but higher frequency doesn’t mean more exposure.”

Go ahead: doomscroll with confidence

With IARC currently watching 321 different agents as possibly carcinogenic to humans – others include aloe vera, road bitumen, carpentry work, petrol, working in the textile industry and even traditional Asian pickled vegetables – Karipidis believes the inclusion of radiofrequency electromagnetic fields is a non-issue that the new research could help destigmatise.

“I think there’s enough evidence for IARC to definitely look at this issue again,” Karpidis said, noting that “although it hasn’t been confirmed, there is some chatter that might happen.”

Aiming to reduce the temperature of the debate, in 2016, ARPANSA founded its Talk to a Scientist program, a hotline that ARPASA research scientist and program manager Rohan Mate said receives over 800 inquiries from the public every year – most of which relate to exposure from mobile phones and base stations.

“We’re hoping these results will be another way we can reassure them about their safety,” Mate said, and “relieve some of their anxiety surrounding engaging with technology and communications technologies.”

Karipidis believes future studies will undoubtedly look at 5G, upcoming 6G and other future technologies with a similarly careful eye – but he believes the new research is a resounding vote of confidence in the safety of now ubiquitous mobile technologies.

“What I want people to understand,” he said, “is that although technology is developing, what comes out of this technology is radio waves.

“Just because tech is changing, what you’re exposed to is not different. It’s the same thing.”