In early August Sam Mitrovic got a notification requesting that he approve a Gmail account recovery attempt – but that was only the start of what the Melbourne IT consultant soon realised was a multi-layered scam powered by a realistic AI voice.

After ignoring the initial notification, Mitrovic – whose firm, Cloudjoy, specialises in Microsoft IT and security solutions – missed a phone call from the US 40 minutes later because he was at his regularly scheduled gym session.

He thought nothing more of it until a week later, when he was returning into the gym and got another notification – followed, again, by a phone call that he picked up and “listened to what they were saying.”

“Previously when you’d receive scam calls, you could pick them straight away,” Mitrovic told Information Age.

“It’s not very convincing, and there’s an accent” that suggests the call may be coming from an offshore scam farm.

This voice, however, was something else: “this was actually a very polite, professional voice with an American accent,” he explained, “and background noise that made it sound like a call centre.”

The voice calmly explained that someone had been trying to log in from Germany and access Mitrovic’s data – a common ruse that scammers use to justify requests for further personal information and access credentials purportedly to verify their identity.

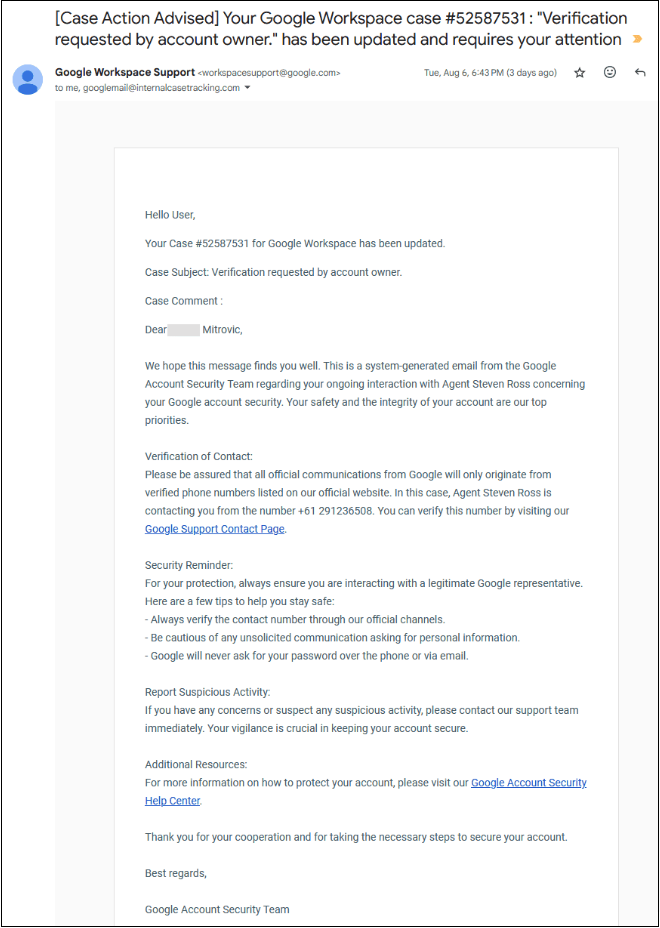

“I asked them to send me an email with all the details,” Mitrovic said, “and it came through straight away” as a boilerplate email alleging that “Agent Steven Ross’ is contacting you from the number +61 291236508”.

That number, Mitrovic realised after online searches turned up reports of similar scams citing the same phone number, is referred to on a legitimate Google support page explaining how to identify calls from the automated Google Assistant system.

Yet the email came from a domain that doesn’t belong to Google – [email protected] – and whose DNS record raises red flags including ownership in Sweden and Norway’s uninhabited Bouvet Island in the Southern Ocean, and a contact email listed as ‘you.can-get-no.info.’

Scammers try to distract victims with references to legitimate Google resources. Image: Supplied

“That’s obviously a big giveaway,” Mitrovic said – as was his experience when another phone call came a few days later.

“Hello?” said what he described as a “perfect and repetitive voice” many times in a row – trying to prompt a silent Mitrovic into talking.

“It was kind of stuck in a loop,” he said. “A real person would say something like ‘are you still there?’ or something like that – but this was just repeating ‘hello’ because, I assume, it didn’t have content from me to respond to.”

Taking scams to a new level

Google is aware of scammers impersonating it, with a spokesperson pointing to advice that “more people are receiving phone calls and unsolicited text messages asking for their personal information” and that “Google will never call you about your account.”

Yet with new voice-based generative AI (GenAI) tools from Google and OpenAI offering convincing conversation skills, cyber criminals are using the technology to target victims en masse.

Deepfake incidents grew 1,530 per cent in the Asia-Pacific region, according to a recent AU10TIX analysis that found the growth contributing to 24 per cent growth in regional fraud rates between 2022 and 2023 – giving APAC the world’s highest fraud rate.

Some 20 per cent of Australian businesses and 36 per cent of consumers were targeted by deepfakes in the last 12 months alone, according to new Mastercard statistics that estimate losses in the tens of millions of dollars.

Fully 22 per cent of those targeted by a deepfake admitted falling for the ruse and losing money, while 36 per cent said the scam was trying to trick them out of personal information rather than money.

Some 44 per cent of deepfakes pretended to be customer service representatives; 38 per cent acted like clients; 34 per cent said they were suppliers or vendors; and others impersonated employees, chief executives, board members, and law enforcement.

“Generative AI technology can be harnessed in both beneficial and concerning ways,” said Mallika Sathi, Australasia vice president for security solutions with Mastercard.

“Increasingly we see it is being used to manipulate consumers and businesses out of money in the form of scams involving deepfakes,” she said.

“Given many victims of these scams are not aware that they have been targeted, this is potentially only the tip of the iceberg.”

Company training is paramount

Companies are increasingly training employees to identify realistic AI deepfakes, with a recent GetApp survey of 241 Australian IT professionals finding that 71 per cent are running deepfake awareness sessions and 47 per cent simulating deepfake attacks.

With AI already creating realistic-looking videos of people, automated lip-syncing software dubbing movies into other languages and adjusting actors’ mouths to match, and even Zoom’s CEO advocating ‘digital twins’ to attend your meetings, video is next.

Another survey found 22 per cent of executives targeted by AI deepfakes – mirroring the experience of US Senator Ben Cardin, who was recently tricked into a Zoom meeting with a video deepfake of former Ukrainian Minister of Foreign Affairs Dymtro Kuleba.

Little wonder that countries like Singapore are pushing to ban deepfakes during elections, a move that Australia is also considering for its 2028 election even as companies like CloudSEK and McAfee automate deepfake detection.

“Social engineering is the oldest trick in the book,” Mitrovic said, “but today’s AI looks pretty good and it’s very convincing – and it’s just going to get better.”