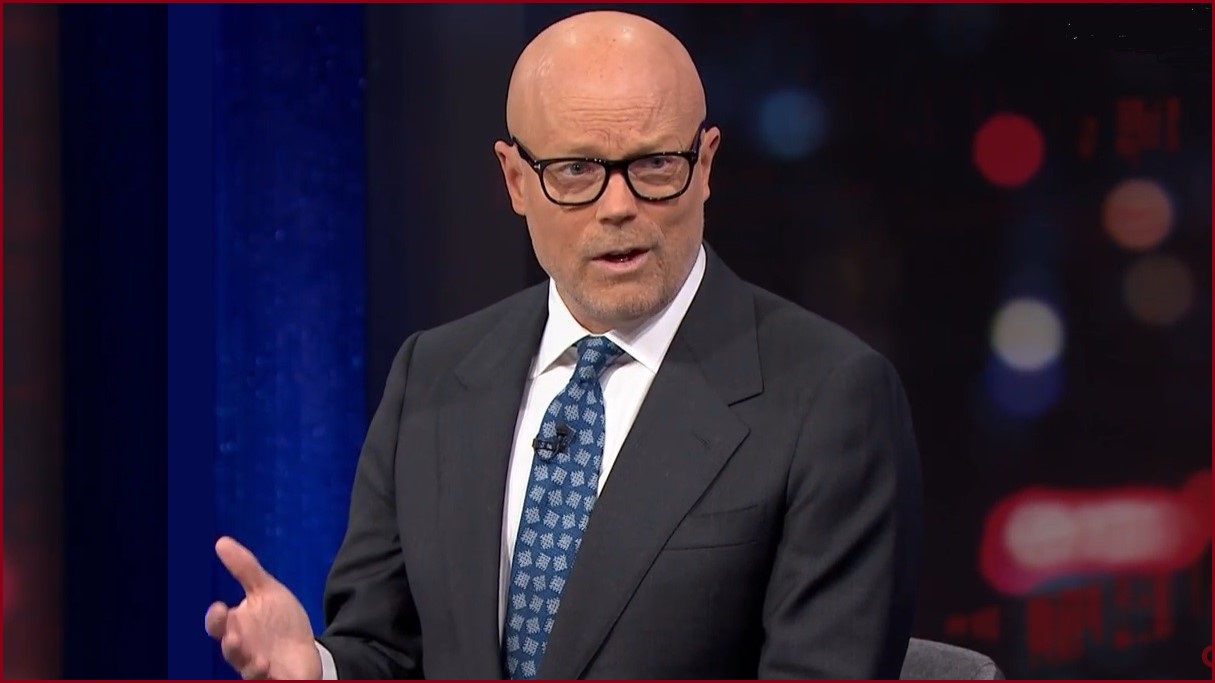

Social media companies are being “contemptuous” to the Australian people and have done “nothing” to help protect their users from scams and crimes, according to former government cyber security tsar Alastair MacGibbon.

MacGibbon, who after a 15-year career with the Australian Federal Police served as special adviser to the Prime Minister on Cyber Security and the head of the Australian Cyber Security Centre, appeared before the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Law Enforcement last week as part of its investigation into the capability of law enforcement to respond to cybercrime.

He discussed the “fundamentally different mindset and approach” required to tackle cybercrime, why education isn’t the answer, and how all levels of government, law enforcement and the private sector need to work together to address the ever-evolving threat landscape.

MacGibbon, who is now the chief strategy officer at cyber security company CyberCX, said that a key issue hampering efforts to combat cybercrime is a lack of cooperation from big tech firms such as Google and Meta, who he said are being “contemptuous towards the Australian people”.

“For Google and Meta, those executives, many of whom I’ve known for decades, have done nothing to help protect consumers,” MacGibbon told the Joint Committee.

“That has nothing to do with encryption, that has to do with being wilfully blind towards criminality on their sites.

“Until the illegal ad or the contact to a potential victim on WhatsApp, Facebook, LinkedIn or Instagram is stopped, and then a telecommunications provider and a bank or financial institution takes more actions to stop that criminality dead somewhere in that ecosystem, there will be victims.”

Government action needed

Google “knows what’s happening on its system” when it comes to cybercrime, and if companies are refusing to act then the government should step in, MacGibbon said.

“All need to raise the tide and lift boats,” he said.

“They can only do it inside their own patch, and that’s where they have their lawful authority to do so.

“If they don’t do that voluntarily, they should be compelled to do so.”

eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant also appeared before the public hearing and described dealings with these tech giants as a “delicate dance” where the firms are often required to be compelled to act.

“I wouldn’t say that the tech industry is known for meaningful transparency and, until we had our basic online safety expectations transparency compensation powers, we were asking questions that we couldn’t get answers to,” Inman Grant told the Committee.

The Australian government has moved to hold these tech firms more accountable for scams that appear on their social media platforms, with draft legislation imposing fines of up to $50 million on companies found to not be doing enough to stamp out scams.

The government has also provided $15 million in funding to the Australian Financial Complaints Authority to beef up its dispute resolution scheme, which will be extended to include social media companies in its remit.

Education not the answer

While there is much discussion about the need for better education of individuals on the risk of scams and cybercrime and how to detect it, MacGibbon said the issue is far too complicated for this sort of approach.

“Unfortunately, unlike skin cancer, where slip, slop, slap, slide and all the other words we’re using are very effective when it comes to sun exposure, there is no equivalent in cybercrime,” he said.

“It’s way too complex a space for simplicity.

“There is some education, but the real failing here is that this is an ecosystem problem until such time as the private and public providers of technologies do more, through either voluntary efforts or compensation, to reduce crime on their systems and there is an overlay of effective law enforcement.

“There is no education that will get us out of this, unfortunately.

“It saddens me to say that as someone who’s spent over 20 years in this space trying to educate on a daily basis.

“But it fails.”

The policing of cybercrime requires a “fundamentally different mindset and approach”, he told the Committee.

“One thing is abundantly clear: we will not solve cybercrime by doing more of the same,” MacGibbon said.

“All of the old business models that we’ve pursued now for two decades are not sufficient to change any of the conditions we find ourselves in.”