Welcome to our three-part series on disinformation, misinformation, and malign influence (DMMI). We look at how DMMI is changing our everyday lives. Here, in part 1, we look at how easily lies can spread on social media and change our perception of what is true.

“PERVOKLASSNIY RUSSIAN HACKERS ATTACK”, read the headline after UK-based Newsquest Media Group was hacked recently, with the message spread across hundreds of local and regional British newspaper websites and readers left confused about what had happened.

The cryptic message was mostly a vanity hack – pervoklassniy means “first class” – but what if the message had been more subtle and believable, like “AUSTRALIAN MP NAMED IN GRIFT SCANDAL” or “BIDEN TO CEDE PRESIDENCY TO HARRIS AFTER ELECTION”?

In a time when truth has never been more important, this hack and others like it – recent years have also seen hacks of other media outlets including Russian and Ukrainian publications, as well as disinformation campaigns related to both sides of every conflict and politically contentious issue – are reminders that truth has never been more subjective.

Disinformation, misinformation, and malign influence (DMMI) long ago became pervasive across social media, but as digital giants roll back their safeguards it has become ever more apparent that much of what you read on the internet today has already been shaped, in subtle and not so subtle ways, by partisan agendas focused on disruption.

Just weeks ago, for example, US government officials revealed that government-backed Chinese and Iranian operatives prepared a broad range of deepfake content to influence that country’s 2020 presidential election.

While that content was reportedly never distributed, officials now worry that technological advancements since then, and the fractious geopolitical situation around Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s war on Hamas, will embolden American enemies to mount DMMI campaigns in an effort to disrupt this year’s election.

Whether the outcome of an election is changed isn’t necessarily the point: simply creating the perception that an election has been manipulated can corrode the perceived legitimacy of a government, creating knock-on effects including fomenting unrest and destabilising otherwise stable societies.

Witness the riots at the US Capitol Building on 6 January 2021, which among other things fed a widespread distrust of political process that has been hard to eradicate: one survey last year, for example, found that almost a third of Americans are still convinced that the 2020 election of President Joe Biden was only due to voter fraud.

Elections aren’t the only target: Israel, for one, recently found to have created 600 fake social media profiles that peppered over 128 US politicians with 2,000 weekly posts urging them to fund Israel’s military campaign.

NSA director Timothy Haugh recently warned about a “very aggressive” Chinese hacking and influence campaign, while generative AI (genAI) giant OpenAI reported that it had shut down Russian, Chinese, Iranian, and Israeli operations that included “deceptive attempts to manipulate public opinion or influence political outcomes without revealing the true identity or intentions of the actors behind them.”

Supporters of Donald Trump stormed the US Capitol building on 6 January, 2021. Photo: Shutterstock

Putting the genie back into the bottle

Based on the narrative on some social media feeds – and reports of fraudsters found to be capitalising on the disruption they cause – readers would be forgiven for believing that insidious fraudsters are regularly twisting election outcomes to their will.

In truth, election fraud is, as a recent Brennan Center for Justice analysis concluded, “vanishingly rare, and does not happen on a scale even close to that necessary to ‘rig’ an election” – a sentiment echoed in an RMIT analysis of Australian voting that found historically close scrutiny of voter processes means the actual incidence of voter fraud is “negligible”.

Yet if they get large enough, DMMI campaigns can win hearts and minds by sustaining destructive narratives and distracting voters from the real issues – a point that Brennan researchers made in recently warning that government and private sector interests must step up to protect the integrity of online information.

A Lowy Institute study of DMMI campaigns during Australia’s 2023 Indigenous Voice Referendum, for example, found non English speaking communities within Australia had been targeted on social media with widespread misinformation, disinformation, online falsehoods and fake news “citing racism, conspiracy theories and colonial denialism.”

“Misleading information was circulated rapidly and broadly through short videos on WeChat and Red,” the researchers reported while warning that “creators of misleading information outperformed community truth-tellers in influencing individual voters.”

Misinformation creators also tend to normalise conspiracy theories, in turn fuelling a spiral of disinformation – a fact that saw similar allegations of widespread fraud during South Korea’s 2022 elections and, the Lowy Institute researchers warn, is likely to resurface “old misleading narratives” in the run-up to Australia’s 2025 federal election.

Indeed, this year promises to be the most significant battle yet against DMMI – with India recently completing its multi-day election, the UK now staring down a 4 July poll, and over 2 billion people in 64 countries presenting for elections this year amidst what researchers believe will be a flood of DMMI content.

As seen with the four-year delay in exposing details of Iranian and Chinese disinformation campaigns, the seeding of subtle untruths into public discourse could well push many voters in these countries towards the right or left.

Whether related to election manipulation or the promotion of debunked scientific and other theories, there has never been more fertile ground for lobbyists, malevolent nation-states, commercial interests, and disaffected individuals to push their agendas by exploiting today’s powerful, far-reaching information platforms.

“Everyone needs to be aware of this, from all across society,” said Eric Nguyen, an ACS branch executive committee member and Gartner Peer Ambassador who was born and raised in Vietnam and learned the power of propaganda firsthand from his journalist father.

“We call out social media companies’ responsibility to help society prevent DMMI,” he said, warning Australians not to be complacent about fighting DMMI.

“We enjoy a peaceful life in Australia, but with the new wave of technology, it is just a different time.”

A majority of Australians in a majority of states and territories voted against an Indigenous Voice to Parliament in 2023. Photo: Shutterstock

From social media to antisocial megaphone

Governmental efforts to fight DMMI have naturally focused on social media, whose broad reach and low barriers to entry have made it deadly effective in amplifying DMMI.

After the Capitol riots, for example, X (the social media network formerly called Twitter) was flooded with conspiracy theories, many bearing hashtags like #stopthesteal, arguing that the election was rigged against former President Donald Trump.

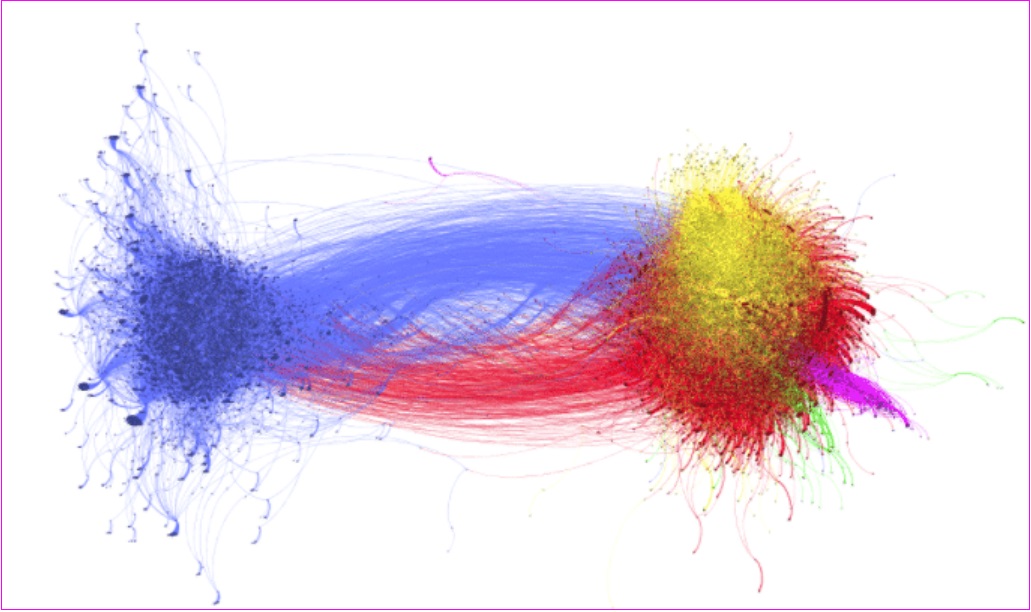

The spread of DMMI after the 2020 US election and Capitol riots has proven fertile ground for data scientists, who have actively applied academic rigour to better understand the flow and amplification of false information.

Researchers at Cornell Tech Social Technologies Lab and Israel’s Technion, for example, analysed 7.6 million tweets and 25.6 million retweets and found that widespread retweeting fed false claims into a feedback loop that amplified those claims – with posts from Trump retweeted over 1.5 million times in the sample and tweets from disgraced lawyer and election conspiracist Lin Wood retweeted over 1 million times.

Visualisation of a Twitter disinformation war shows amplification of claims and counter-claims between voter-fraud claimants (right) and their opponents (left).

Another Cornell Tech analysis found that image-based #stopthesteal posts spread like wildfire – with nearly half of such images reaching their “half life” within three hours, and many containing quotations or other sentences in an apparent attempt to avoid text-based content filters.

Analysis of yet another set of more than 49 million tweets, connected to 456 separate misinformation stories spread about the US election in the last months of 2020, found that Trump “and other pro-Trump elites in media and politics set an expectation of voter fraud and then eagerly amplified any and every claim about election issues, often with voter fraud framing” across 307 distinct narratives designed to sow doubt in that year’s election.

Proponents of such misinformation often carpet-bomb social media networks, delivering incendiary false messages that catalyse many users’ existing feelings and can quickly reach thousands or millions of people – spilling into the real world as users assemble for protests or violence that catch police unawares.

By utilising the very tools that make social media so effective, the rapid spread of DMMI often sweeps aside the truth in the name of sensationalism – as was seen recently when Seven News erroneously named university student Benjamin Cohen as the knife-wielding killer in the Bondi Junction attacks.

The allegations were quickly retweeted on X, including by accounts with millions of followers that used the misinformation to further anti-semitic and anti-Muslim agendas – effectively smearing Cohen’s reputation in moments even though he had nothing to do with the attack.

Cohen is now pushing the NSW Police to criminally prosecute the holders of the accounts that amplified the message so quickly – a significant step that, were it not so unlikely to succeed, might have motivated some online DMMI proponents to think before they retweet.

Analysis of past DMMI tactics promises to help social media networks hone content filters, or develop entirely new ones, to identify and counteract malicious content – or it could, were social media sites like X not so determined to straddle the gulf between truth and perception that continues to taint the trustworthiness of their content.

X – which was last year booted from the Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation (ACDPM) for a “serious” breach of its controls, has walked back anti-DMMI protections by firing global trust and safety staff; reinstating accounts of users previously banned for content violations; and trimming the number of moderators by more than half.

The network’s lack of observably effective content controls has brought it in the line of fire of European regulators – who recently warned Musk, as well as fellow billionaire and social media gatekeeper Mark Zuckerberg, of their legal obligations to check the dissemination of illegal content and disinformation that exploded after the commencement of the Israel-Hamas war.

Ensuring that Australia’s social media networks minimise DMMI remains a key priority for the likes of Minister for Communications Michelle Rowland, who has been outspoken about its risks and is engaged with the debate about how to improve the situation.

“The lack of action on misinformation and disinformation sows division, undermines trust and tears at the fabric of society,” Rowland said, “[but] with the right incentives, social media can contribute more to the welfare of society.”

Read more: