The Australian Federal Police (AFP) is teaming up with experts at Monash University to sabotage the AI technology behind an uptick in deepfakes and abuse material.

The AFP and Monash announced Monday they were developing a “new disruption tool” which could “turn the tech tables” on cybercriminals by slowing and stopping the production of malicious AI-generated images.

Dubbed ‘Silverer’, the new tool has been designed to thwart AI-generated deepfake images and videos, child abuse material (CSAM), and “extremist technology propaganda” by using a tactic known as ‘data poisoning’.

In practice, this involves subtly altering the data used in AI training datasets to make it “significantly more difficult” for malicious actors to produce, manipulate or misuse images with AI tools.

Funded via the AFP’s Federal Government Confiscated Assets Account and developed under the AFP and Monash’s AI for Law Enforcement and Community Safety (AILECS) Lab, Silverer was launched to meet AILECS’ specific focus on countering online child exploitation.

“The rapidly growing ability of criminals to create malicious, sexually explicit deepfakes using open source tools – such as Stable Diffusion and Flux – inspired the lab to begin researching tools to give ordinary internet users more ability to protect their images from use by those criminals,” Silverer project lead and PhD candidate Elizabeth Perry told Information Age.

At the time of writing, Silverer has been in development for 12 months and a prototype version of the tool is currently “in discussions” to be used internally at the AFP.

A dose of digital poison

Silverer’s prototype has been designed for users to run at a local level – if a person were to upload an image to social media, for example, they could first modify the photo with Silverer to bolster their defences against any would-be cybercriminals trying to manipulate their likeness.

Silverer achieves this by delivering what the AFP and Monash described as a “dose of digital poison” where a subtle, pixel-level pattern is added to the image to fool AI models into creating “inaccurate, skewed or corrupted results” rather than a reliable image of the victim.

“This will alter the pixels to trick AI models and the resulting generations will be very low-quality, covered in blurry patterns, or completely unrecognisable,” said Perry.

She added the name Silverer was a nod to the silver used in making mirrors.

“In this case, it’s like slipping silver behind the glass, so when someone tries to look through it, they just end up with a completely useless reflection,” she said.

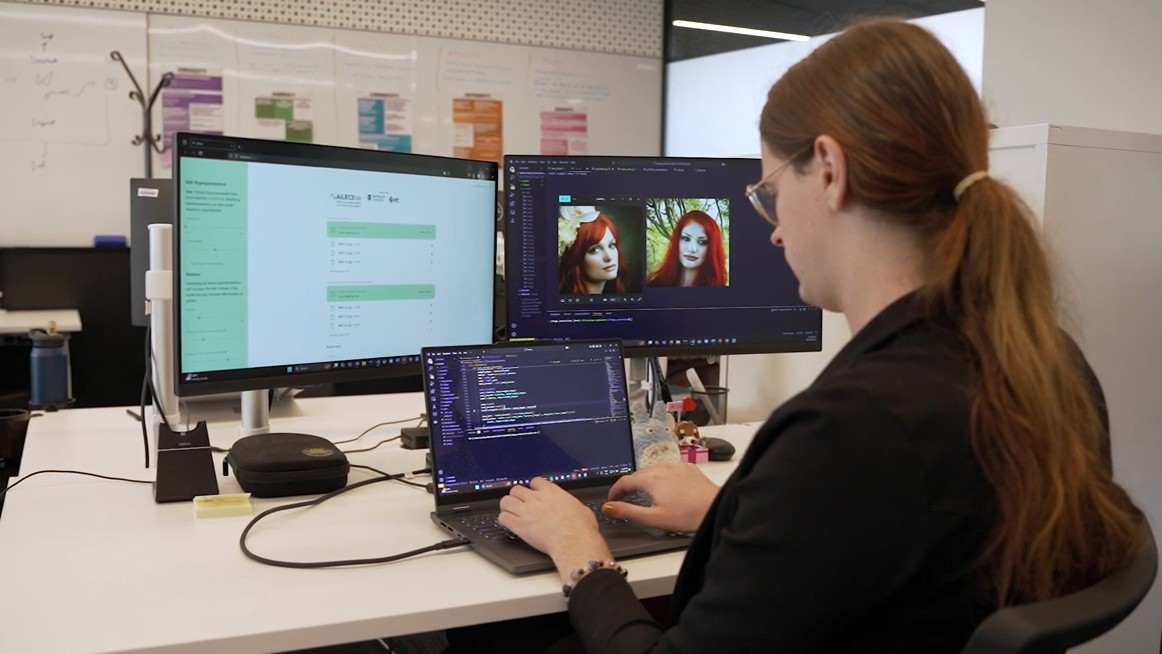

Silverer project lead Elizabeth Perry says the tool alters pixels 'to trick AI models'. Image: AFP / Supplied

Deepfake plague calls for new tech

Speaking with Information Age, Perry said AI-generated CSAM not only causes “harms and trauma” to victims, but also threatens to “overwhelm law enforcement and waste valuable resources”.

Indeed, AFP has announced arrests, charges and prison sentences for at least six Australian men since March 2024, while in September, Australia imposed a first-of-its-kind, $343,500 penalty against a man for making and posting 12 non-consensual deepfakes of six Australian women.

Recent data from the eSafety Commissioner further revealed at least one deepfake incident is taking place weekly in Australian schools.

AFP Commander Rob Nelson said although data-poisoning technologies such as Silverer were still in their infancy, they showed promising early results for law-enforcement.

“We don’t anticipate any single method will be capable of stopping the malicious use or re-creation of data, however, what we are doing is similar to placing speed bumps on an illegal drag racing strip,” said Nelson.

“We are building hurdles to make it difficult for people to misuse these technologies.”

Perry told Information Age the prototype has not been without its challenges – namely, the newcoming technology had proven “quite computationally intensive” and would require a “reasonably strong” consumer grade laptop to run.

And although the lab is “investigating the possibility of a server-side deployment”, Perry also observed the possibility of cybercriminals getting around the solution.

“As with all arms races, in cybersecurity or conventional warfare, there is always tension between the tools of the attacker and the defender,” she said.

“Silverer represents an improvement in the quality of the defenses available to ordinary users, but we certainly anticipate the possibility that a very committed attacker would use tools to attempt to remove Silverer's poisoning.”

“If we can even deter a few would-be criminals, though, we will be glad to have been able to use AI for good.”

Fake pictures, fake sounds

Separately to AILECS’ new data-poisoning tool, researchers from national science agency CSIRO, Federation University Australia and RMIT University announced a new method for detecting audio deepfakes.

Named ‘Rehearsal with Auxiliary-Informed Sampling (RAIS)’, the technique automatically stores known deepfake examples to help inform its detection measures and keep up with evolving deepfake styles.

Researchers wrote audio deepfakes were a “growing threat in cybercrime” that introduced risks for voice-based biometric authentication systems, impersonation, and disinformation.

Indeed, experts recently said it was “highly plausible” that Qantas’ June data breach involved AI-based voice deepfakes.

“We want these detection systems to learn the new deepfakes without having to train the model again from scratch,” said Dr Kristen Moore, cybersecurity expert at CSIRO’s digital research network Data61.

“RAIS solves this by automatically selecting and storing a small, but diverse set of past examples, including hidden audio traits that humans may not even notice, to help the AI learn the new deepfake styles without forgetting the old ones.”

The code for RAIS is currently available to the public on GitHub.