Australia needs to reduce its "risk aversion” in order to improve its lagging research and development (R&D) sector and fragmented innovation ecosystem, according to industry experts.

The nation has struggled to capitalise on innovations developed by universities and startups, and has seen their intellectual property taken overseas in search of greater funding, a panel of industry insiders told the ACS Election Forum in Sydney on Tuesday.

Phil Morle, a partner at CSIRO’s venture capital firm Main Sequence, said while there was still funding for scaleups and “a language of innovation” in Australia, companies were leaving the country “time and time again”.

"Unfortunately, there are very few growth funds here in Australia,” he said.

“[There are] very few big embeddings of a startup in a big company, or as a government customer, for example.

“What that means is … the moment comes where funding rounds are getting bigger and bigger.

“… You look around and you don't find [funding] in Australia, and you look overseas, you find it, and you move — the whole company goes.”

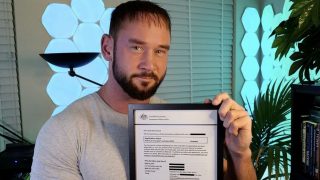

Inventor Mic Black, co-founder of bioelectronics startup Rainstick, argued Australia was too risk averse and its R&D system needed greater tax incentives to allow entrepreneurs to “go for bigger moonshots”.

While Black said Rainstick had received “quite a warm welcome” from Australia’s funding ecosystem, he worried it was not a common experience for startups.

“There's a whole bunch of support that's there — but that risk appetite piece, it's almost a cultural problem rather than a facility problem,” he said.

Australia’s domestic investment in R&D has declined over the past 15 years, and dropped to 1.66 per cent of GDP in 2022 — well below the 2.7 per cent average in the OECD group of developed nations.

What can governments do?

Jane O’Dwyer, chief executive of Cooperative Research Australia, said she agreed with Black that Australia needed to “address our risk aversion” around R&D.

O’Dwyer called for Australia to shift from three to four-year fixed terms in federal government, to help achieve that goal.

“That's probably likely to drive a greater tolerance of risk,” she argued.

Governments could play a role in procurement by being “that first hungry customer” for local startups, O'Dwyer added, but authorities also needed to improve their understanding of technology.

“I think we've got an issue where government lags way behind on adoption of artificial intelligence and technology, and we need them to make a big leap so they understand what the opportunities are ahead of us,” she said.

Australia’s domestic investment in R&D was 1.66 per cent of GDP in 2022 — well below the average in the OECD group of nations. Image: Shutterstock

Australia’s domestic investment in R&D was 1.66 per cent of GDP in 2022 — well below the average in the OECD group of nations. Image: Shutterstock

Emeritus Professor Roy Green, the special innovation advisor at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS), argued there was “a huge amount of [government] money floating around” for Australian scaleups, which many people were simply not aware of.

“This government has actually created the ingredients of what, if it follows through with a second term, could be a very systemic approach to scaling up early-stage companies,” he said.

He cited schemes such as the Future Made in Australia program, the National Reconstruction Fund, and the Powering the Regions fund, and argued “most people don't even know they exist”.

“It's a mind-numbing number of programs,” Green said.

“That's the problem — people can't get their head around it.

“But if you add it all up, it comes to about $100 billion, and we can do a lot with $100 billion.”

What can universities do?

Charlie Ill, the chief executive of Asia-Pacific early-stage venture capital (VC) firm Investible, argued there was actually “a very high risk appetite” in universities when it came to inventing or discovering new things, but they often struggled to capitalise on their work.

Some researchers and inventors were reluctant to leave the security of their university jobs, he said, while many universities also wanted guaranteed returns from their patents or technologies.

“But then there's also this structural issue where there is a very bureaucratic or legal processing system to approve the issuance or the spin-off of that technology,” he said.

Ill said he encouraged universities to engage with venture capital firms with track records in particular fields, and argued there was value in government helping to incentivise and reward the commercialisation of university innovations.

“Ultimately, incentivising the VCs and the capital markets to actually become deeper and more diversified and be able to take those risks is all part of, I think, putting the tax money to work,” he said.

An ongoing review of Australia’s R&D landscape has found the nation's “siloed” innovation system and “a business community that is largely indifferent” meant Australia's economy was “unprepared to achieve sustained growth”.

The independent review — the first in almost two decades — was initiated by the federal government and is expected to report its full findings by the end of 2025.

Roy Green from UTS said the review’s current findings pointed to declines in Australian manufacturing, business expenditure on R&D, and ultimately the country’s flailing productivity.

"Which tells us that just spending money on R&D is not going to solve a broader question of our narrow trade and industrial structure based on the export of unprocessed raw materials,” he said.