When Australian artificial intelligence expert Dr Kobi Leins declined a medical specialist’s request to use AI transcription software during her child’s upcoming appointment, the practice told her the practitioner required the technology be used and Leins was "welcome to seek an alternative" provider.

The specialist’s “high workload and limited time” meant they were now “unable to perform timely assessments without the use of AI transcribing tools”, the practice said in an email seen by Information Age.

“They gave me the choice of proceeding with the AI that they were insisting on, or to find another practitioner,” Leins said.

The appointment was cancelled, and her deposit refunded.

In Australia, healthcare providers can decide to not consult with a patient for any reason — except in emergency situations — provided they facilitate the patient’s ongoing care in some way.

The AI system used by the practice Leins had booked was an Australian platform which transcribed sessions to maintain the specialist’s notes about patients and their health, the practice told her.

It was a system whose privacy and security capabilities Leins had previously reviewed as part of her work in AI governance — and one she said she would not want her child’s data “anywhere near”.

The rise of AI scribes in the doctor’s office

AI scribes are becoming more common in Australian medical practices, with around 20 per cent of GPs — but fewer specialists — using the technology according to recent industry polls.

The software is typically marketed around saving practitioners time, improving their engagement with patients, and reducing burnout.

The generative AI tech can write, organise, and analyse notes about health concerns, and some can even propose follow-up tasks for practitioners, complete administration such as drafting letters and forms, and make follow-up phone calls to patients.

But unlike most medical devices, AI scribes remain largely unregulated, leaving it up to individual healthcare practices to decide which tools they want to use, and how.

AI scribes have already presented risks for both patients and doctors in areas such as accuracy and data retention, according to University of Queensland associate professor of information systems, Dr Saeed Akhlaghpour.

Some clinicians have reported AI scribes making incorrect diagnoses, he said.

Allowing the software to receive new features "without adequate review or re-consent" from users was also a risk, Akhlaghpour said — as was vendors potentially processing sensitive data outside of Australia.

“If a vendor processes data offshore, patient information may be subject to weaker protections than those under the Australian Privacy Principles,” he said.

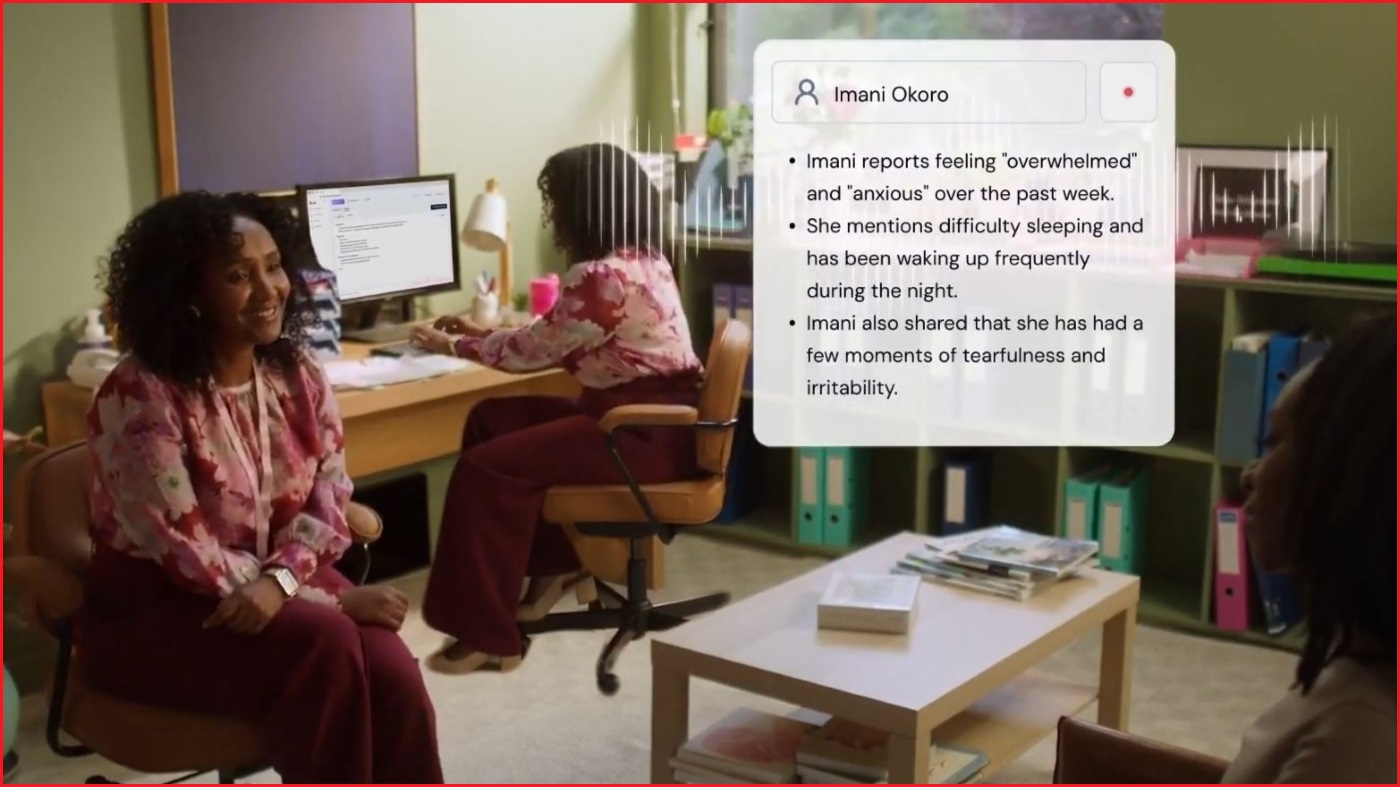

AI scribes from companies such as Heidi and Lyrebird take notes for practitioners during medical appointments. Image: YouTube / Heidi Health

Leins, who previously held senior AI and data ethics roles at health insurance company Bupa and the National Australia Bank (NAB), said she had reviewed over 200 AI tools during her career.

While she was “disappointed” by the response of the medical specialist she had booked with, Leins said she was more surprised to hear from the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) that AI scribes were not regulated by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).

“The question is, who has the onus to prove that they’re good enough, or that they’re fit for purpose and legally compliant?” she said.

Medical practices were likely being approached by AI companies and convinced to purchase their “magical solution”, Leins suggested, despite often not being qualified or able to review the tools’ privacy and security standards for themselves.

AI scribes could be reviewed and regulated nationally, she argued, so there was less burden on individual practitioners and fewer risks for patients.

Should AI scribes be regulated in healthcare?

A spokesperson for AHPRA did not take a position on whether AI scribes in healthcare should be regulated by the TGA, when contacted by Information Age.

They acknowledged new AI tools had presented “some new practice management questions for practitioners” and said regulators were working with other agencies to develop further guidance for medical professionals.

“AHPRA recognises that helping practitioners talk with patients about AI can build public trust and support its safe use in healthcare,” they said.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) also did not have a position on whether AI scribes should be regulated by the TGA, but has previously stated AI systems “must be evaluated over time … to ensure they are still fit for purpose”.

“There may be a need to establish a new Australian regulatory body to fill gaps in existing government portfolios and legislative instruments,” the organisation stated in its position on AI in primary care.

Australia's medical regulator AHPRA says AI scribes raise 'some new practice management questions for practitioners'. Image: Shutterstock

Associate professor Akhlaghpour said regulating AI scribes in healthcare with “targeted, risk-based national oversight” would help prevent potential issues around privacy, security, and liability.

“While AI scribes claim they are not medical devices, some already function in ways that meet the definition, such as proposing diagnoses or treatments, which could require pre-market approval under the Therapeutic Goods Act,” he said.

A TGA review published in July found some AI scribes which proposed diagnoses or treatment options for patients were “potentially being supplied in breach of the Act” and may require pre-market approval.

“Regulation should set baseline requirements for encryption, retention, cross-border transfers, and transparency about what is recorded and how it is used,” Akhlaghpour said.

Asked by ABC News on Thursday whether he would be comfortable with his own doctor using an AI scribe, Health Minister Mark Butler described the technology as “the future” of medical appointments.

He said the federal government was “grappling with … making sure that it’s done in a safe way”.

“I know it's being used already, but we do have to be very careful about what happens to the data and the information,” Butler said.

The question of consent

Leins said she worried other practitioners were refusing treatment to clients if they did not agree to use their AI-based tools or scribes.

"The concern for me is an industry position which doesn’t leave patients with a choice,” she said.

AHPRA has previously noted that practitioners are required to gain informed consent from patients for the use of AI scribes, “as there may be criminal implications if consent is not obtained before recording”.

The agency did not comment on whether a practitioner should use traditional documentation methods if a client refused an AI scribe — and there is nothing stopping medical practices from turning away patients who do not consent to their use.

“Equally, patients have no responsibility to consult a specific medical practitioner and can choose to end a doctor patient relationship at any time, for any reason,” AHPRA said.

Associate professor Akhlaghpour said he and his colleagues’ research had shown patient consent was “central to trust in AI-enabled healthcare”.

“Patients are more willing to give meaningful consent when they are told clearly what is being recorded, where data will be stored, who will access it, and for what purposes,” he said.

“Trust grows when clinicians explain safeguards in plain language and can demonstrate control over the tool — for example, being able to pause or delete recordings.

“Willingness drops when there is vagueness around data use, suspicion that information may be shared beyond the care team, or no visible way to opt out.”