Australia came off relatively unscathed compared to other countries, but a new analysis of 93.7 billion stolen ‘cookies’ is a reminder that cybercriminals will stop at nothing to steal your personal information – so why are so many websites still collecting it?

Conducted by security firms NordStellar and NordVPN, the analysis delved into a cache of stolen cookies – small files that websites store on your computer or mobile device to store your personal preferences and information – that were published to the dark web.

Cookies come in many different types, predominantly first-party cookies – which might, for example, prefill forms or store your username so you don’t have to enter it next time you log on – and third-party cookies used to track your activity and target advertising.

More than a third of the tracking cookies in the data set were related to Google, with advertising-heavy sites like YouTube, Microsoft, Bing, MSN, Amazon, LinkedIn, Yahoo, Facebook, and TikTok all well represented on that leaderboard.

More persistent ‘super cookies’ and ‘zombie cookies’ use sneaky techniques to embed themselves in your web browser’s local storage, ensuring they can watch everything you do and making them extremely difficult to remove.

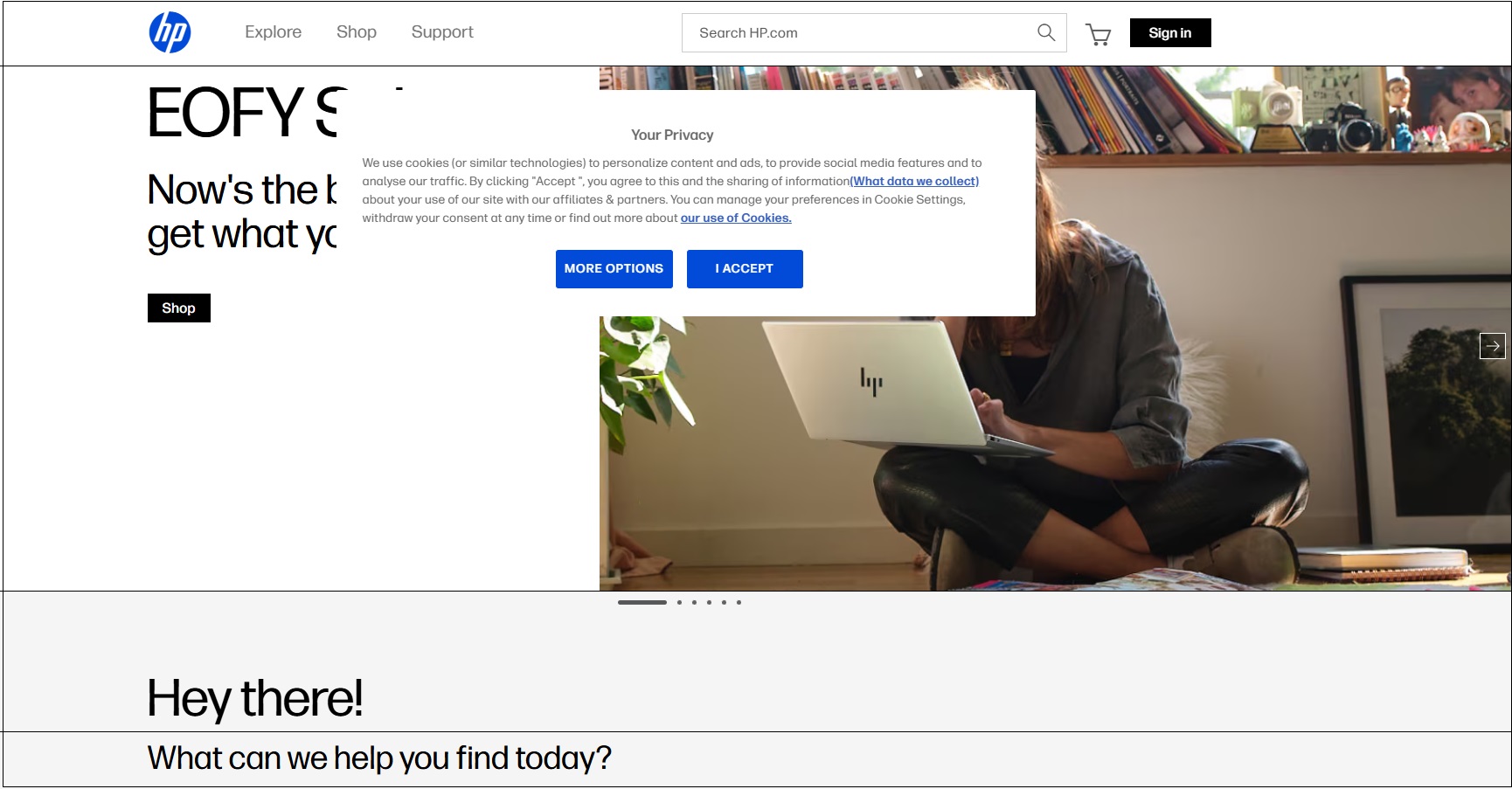

It is good practice to give users an option. Photo: Supplied

Cookies are categorised by type and NordVPN found that 19 per cent of the entries in the data set are ‘ID’ related, with 1.2 billion ‘session’, 272.9 million ‘auth’, and 61.2 million ‘login’ cookies that can be used to take over a victim’s live online session.

Session cookies “are a goldmine,” the analysts warn, because “they let attackers skip login pages altogether” – with reports of cookies enabling social media takeovers, impersonation of targets, bypassing 2FA, breaching networks, and more.

With cookies including data like email addresses, gender, birthday, the analysis warns that “even the most seemingly unimportant cookies can do a lot of damage to you or your business – and once one door is open, it isn’t that difficult to open others.”

Lead indicators of cybercriminal activity

The analysed cookie collection is just one of innumerable mountains of data that are available for purchase or download on the dark web – but where did they all come from?

The wide variety of cookie types in the breach suggest that they were captured when their owners were tricked into installing malicious ‘infostealer’ malware that scrapes them from the web browsers of infected systems.

The vague notice on the Chemist Warehouse website. Photo: Supplied

Indeed, NordVPN was able to identify 38 different types of malware that were used to collect the data in the breach, with the likes of Redline, Vidar, Lumma-c2, Meta, and Raccoon most frequently encountered.

Cookies from users in Brazil, Indonesia, the United States, Vietnam, Philippines, Turkey, Pakistan, Egypt, and Thailand were the most frequently represented – likely a symptom of generally poor cyber hygiene in those countries – with Australia outside the top 20.

Yet that doesn’t make Australians safe, particularly since, despite years of government claims to be making the Internet safer for users, current law doesn’t require Australian websites to let users decline to accept cookies that may well be resold by criminals.

Whereas European Union (EU) general data protection regulations (GDPR) have tightened controls on cookies that are considered personal information, in Australia opt-outs are nothing more than best practice unless selling to EU customers.

Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) do require companies “to be transparent about the types of data they collect and how it is used, stored, and handled”, Legalvision corporate and commercial lawyer Sharon Chen explained.

But that doesn’t mean they need your consent to store cookies – only to make sure you can find out what data they’re collecting, and why.

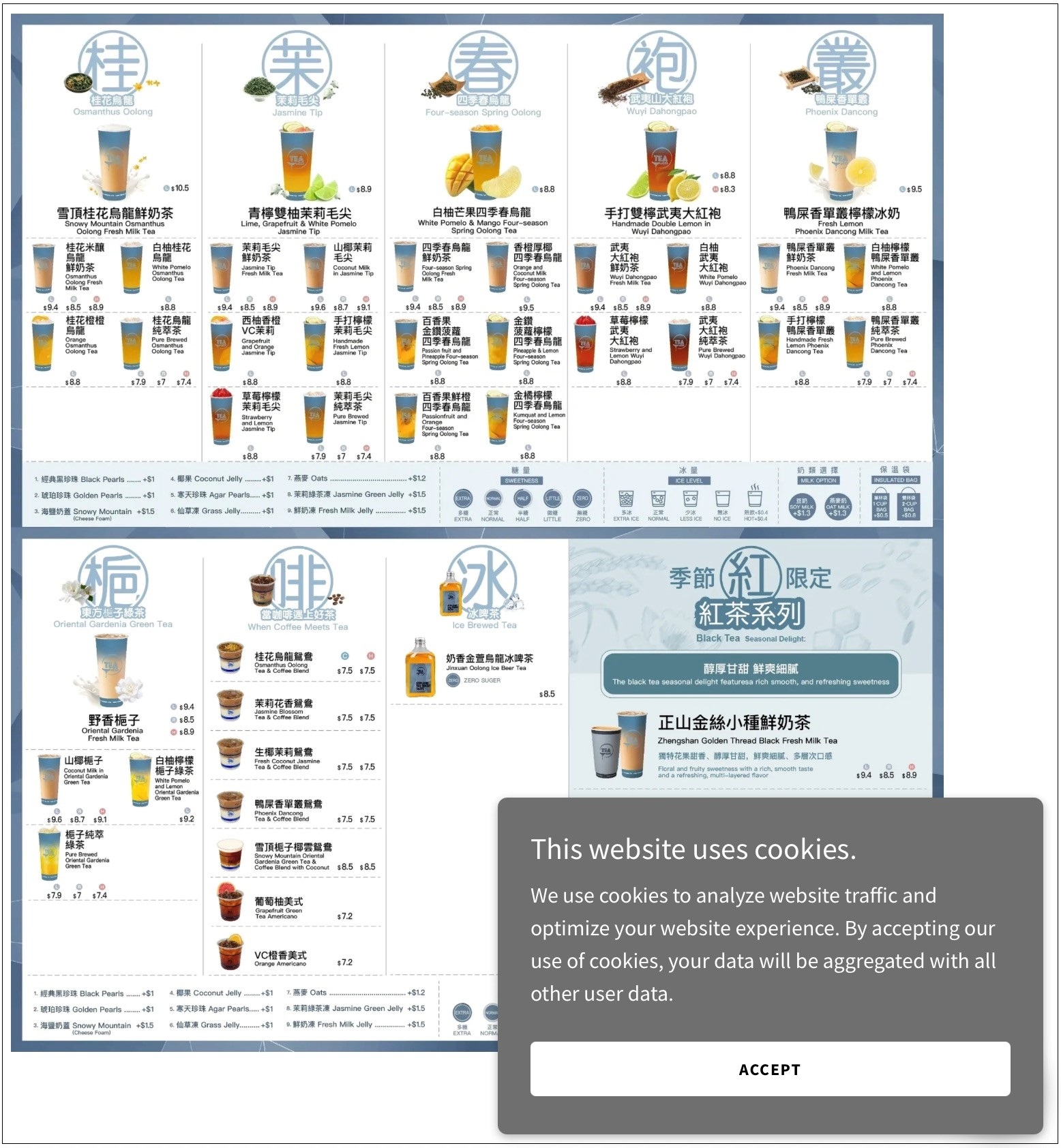

Perusing the menu at TeaAndCo? You’ll get a side order of cookies too. But not the yummy kind. Photo: Supplied

Most companies recognise that users value transparency, but not all of them care as much as others.

Many users suffer ‘cookie fatigue’ – reflexively clicking ‘Accept’ to clear intrusive popups – yet this can be dangerous, HP security experts recently warned, with cybercriminals caught tainting sites with malware that loads when you accept the cookies.

Changing the playing field?

Australia’s outdated privacy laws are undergoing protracted review, and changes that are finally gaining traction this year may force the point with Australian operators.

Yet in the meantime, a range of technological options give you some control: cookie controls are built into some web browsers, with others providing control of cookies with browser extensions offering cookie blocking, disabling and deletion.

And while in 2020 Google began a plan to phase out cookies by this year, its alternate FLoC and Privacy Sandbox technologies were so poorly received that it backtracked last December and is now focused on tightening in-browser cookie controls.

Australian companies running websites are best to err on the side of caution by giving users more consent options and visibility of privacy policies, as well as the ability to reject cookies even if it might erase shopping carts or otherwise limit functionality.

Meanwhile, experts advise users to think proactively about their exposure to cookies –rejecting unnecessary cookies where possible, habitually cleaning out old cookies, and using security tools to block malware that could expose them.

While “not all information collected by cookies is sufficient to identify a website user,” Chen said, “your business should nevertheless be considering disclosing your use of cookies on your website through a privacy policy.”