A British cybersecurity expert has landed a coveted tech visa for exceptional talent after he hacked an Australian government department and exposed a “critical vulnerability”.

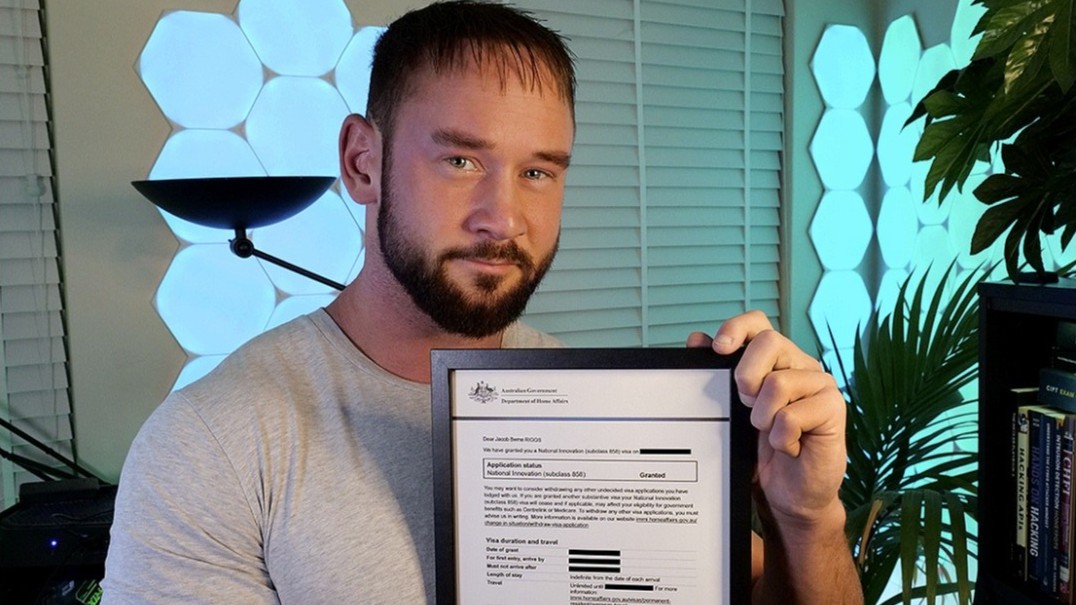

Jacob Riggs, a British national with more than a decade of experience in the cyber sector, was granted an 858 National Innovation visa in December, less than a year after he applied for the invitation-only visa.

The National Innovation visa replaced the Global Talent visa in late 2024 and is a permanent visa for individuals who have an “internationally recognised record of exceptional and outstanding achievement in an eligible area”.

This visa has an approval rate of less than 1 per cent, according to VisaEnvoy, with more than 9,000 expressions of interest submitted, just over 300 invitations issued and about 85 visas ultimately granted.

Riggs told Information Age that his reaction to finding out he had been approved for the coveted visa was a “mixture of relief, disbelief and excitement”.

“I was very aware of how selective the 858 process is, so when the approval came through it took a moment to properly sink in,” Riggs told Information Age.

“It genuinely felt like one of those rare life-changing moments.

“I’ll certainly be continuing my work in cybersecurity and contributing where my hands-on and leadership experience is most useful.”

With the visa, Riggs will now be able to work and live in Australia permanently, sponsor relatives to move to the country and apply for citizenship.

Riggs is now based in Sydney and is able to apply for Australian citizenship. Photo: Supplied

Showing his skills

Riggs applied for the visa early last year, and included 60 pages of evidence of his expertise, including bug bounty payouts, recognition letters from universities and governments and proof he has identified vulnerabilities to major tech firms.

After waiting seven months, Riggs decided to take matters into his own hands and demonstrate his cyber expertise to the Australian government in a practical way.

“Given the bar the 858 sets, it became clear during the application process that I should also make efforts to show the current value in my capabilities,” Riggs wrote in a blog post.

“With my application still sitting in the review queue and the portal continuing to accept changes to evidence, I decided to start looking at the Australian government’s attack surface for vulnerabilities.”

After discovering the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT) Vulnerability Disclosure Policy, which allows researchers and ethical hackers to responsibly share potential vulnerabilities with the department, he set about trying to hack the government.

“That provided a legitimate, ethical framework for me to carry out my hacking responsibly,” Riggs said.

Less than two hours later, Riggs had identified what he said was an “exploitable critical severity vulnerability”, which he reported to DFAT.

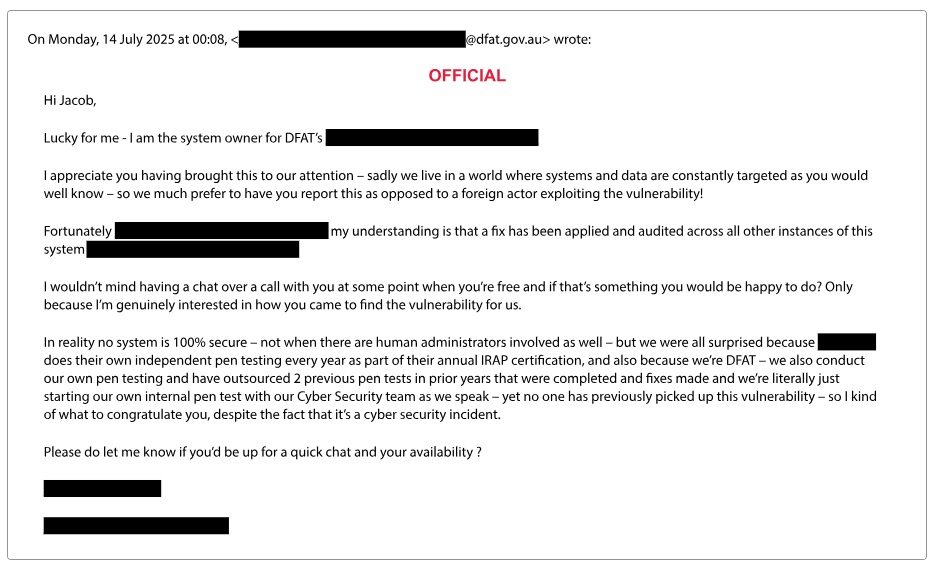

A director at the department quickly responded to Riggs and said a fix had been applied for the vulnerability, even going as far as to ask how he had found it.

DFAT wanted to know how Riggs had found the vulnerabillity. Image: Supplied

“Finding the vulnerability was not easy,” Riggs said.

“It became clear to me from the start that DFAT takes its security seriously.”

The 858 Innovation visa process requires applicants to show recognised achievement in their field, such as through a Nobel Prize or Olympic gold medal.

But doing this is difficult in the cybersecurity sector, which is one of the priority areas under the scheme.

Demonstrated impact

Soon after disclosing the vulnerability, Riggs was approved for the 858 Innovation visa.

“The strength of the 858 process is that it appears to look beyond traditional credentials by also focusing on demonstrated impact,” Riggs said.

“In fields like mine, that real-world experience matters more than titles or academic achievements alone.

“I also think a process that rewards sustained contribution and measurable expertise is well-suited to attracting genuinely exceptional talent.”

Riggs is now one of just four people listed publicly on DFAT’s vulnerability disclosure honour roll on its website.

There have been long-running concerns about the skills gap in Australia’s cybersecurity sector, and some efforts to fill this through highly skilled migration.

According to Jobs and Skills Australia’s Occupational Shortage List 2025, a wide range of cyber roles are still in shortage around the country.

Roles such as cybersecurity governance, risk and compliance specialists, cybersecurity engineers and operations coordinators and software testers are in shortage in nearly all states and territories.

Last month, it was revealed that scammers were impersonating senior officers in the Department of Home Affairs with an aim to trick visa applicants into paying fake application fees.

These scammers were offering to assist individuals with their visa applications, then trick them into making “extra payments” to speed up the process.