Parts of the medical profession were not exactly winning friends with their approach to sourcing computers in 1982.

Dr Ian Colclough wrote in the February 1982 edition of Australian Business Computer that the "number of computer installations in medical practices is growing slowly but steadily."

"Some people believe that by the end of the 1980s almost every medical practice will have its own computer system," he noted.

While that should have been a boon for computer sellers, some quickly tired of the tactics used by some doctors to procure their machines.

Ross Davey lamented medical practitioners he said were "unaware of, and unsympathetic to, the economic facts of life of professional computer companies".

"Most of these companies are basically reputable, and although requiring a 'bomb under them' from time to time, will try to maintain a good name by servicing the client's needs," he assured the magazine.

"Yet I continually find doctors shopping for computers like they are buying a used car.

"They subject the companies to high selling costs by leading the salesmen on and pitting one company against another to extract a few hundred dollars savings."

Davey attributed this attitude to false expectations planted by freelance consultants or "friends in the business" that medical systems could be stood up in little more than a weekend.

However, those expectations led to practitioners wanting "extraordinary concessions ... which obviously are going to be uneconomic for the computer company to live up to."

"It should only take a little common sense for these people to realise that fairly stringent economic criteria prevail with all professional computer organisations and that mainly the buyer loses when unreasonable demands are placed upon the supplier," Davey noted.

Medical practitioners, however, were also battling to get up to speed with computer systems and what they should cost.

"The difficulty facing doctors today is how to decide which system to buy for the practice and how much the practice should spend when buying a system," Dr Colclough said.

Better care

Medical practitioners were starting to buy computers because they could see their value, according to Dr Colclough, although progress on that front had been slower than potentially expected.

"The fee for service structure of the Australian health care system creates a considerable amount of paperwork in a medical practice," he said.

"Doctors have been slow to realise that they can curtail their overheads and run a more efficient practice by using computers to help control the patient billing and practice accounting aspects of their practices."

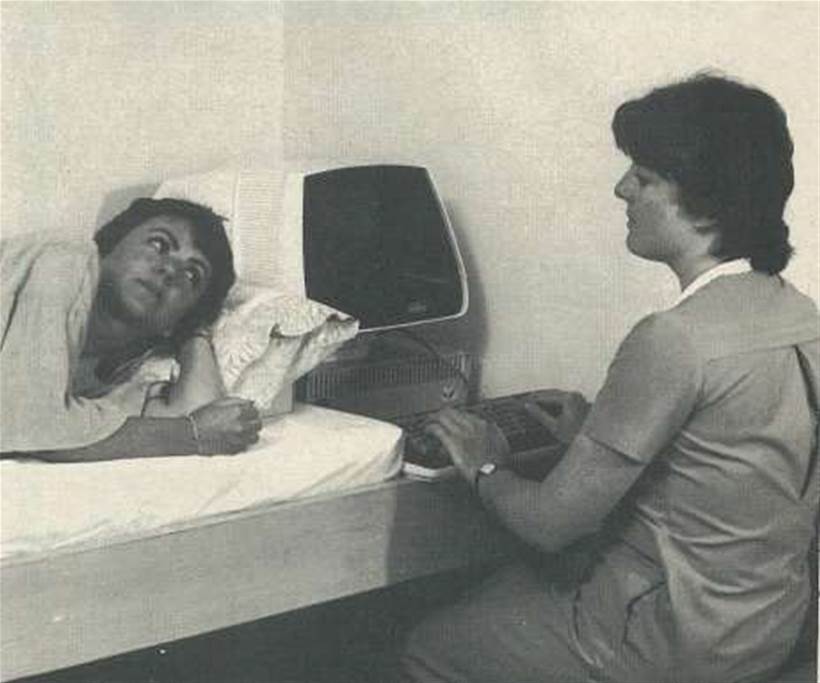

Aside from computerised accounting, "some doctors have gone even further and have recognised the tremendous benefits offered to the patient by computerising the medical record."

"No longer do these doctors have to flip through bits and pieces of paper all filed haphazardly in folders or on cards to find the information they need and want about their patients' medications and illnesses," Dr Colclough said.

"These doctors can instantly have access to any information in the patient medical record at the push of a button.

"All this helps the doctor to provide more effective care to the patient."

Fast forward to 2012 – a full 30 years later – and Australia finally has an eHealth records system called the personally controlled eHealth Record (PCEHR).

However, adoption has perhaps been slower than one might have expected given the interest over the past three decades.