One of the most memorable and dramatic cabinet reshuffles in recent times has resulted in immigration being passed from the hands of Minister for Home Affairs Peter Dutton to new Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs David Coleman.

Under the new arrangements Coleman will not hold a cabinet position, meaning immigration will ultimately still fall under Dutton and the Department of Home Affairs.

But the new ministerial arrangements mark yet another twist in Australia’s immigration history – specifically skilled migration – which has been a major bone of contention in this Coalition Government.

Then Minister for Citizenship and Multicultural Alan Tudge recently delivered a speech to the Business Council of Australia detailing the “recruitment challenge” Australia now faces and outlining the government’s policies.

“The case for further skilled migration is strong,” he said. “But this does not translate to meaning that the more skilled migrants the better.”

“There is a balance to be made.”

Going back: 457 visas

Introduced by John Howard at the beginning of his tenure in 1996, the Temporary Work (Skilled) (Subclass 457) Visa was designed to allow workers with key skills to temporarily enter and work in the country.

Under the 457 visa workers in a list of strategic occupations could be sponsored by an employer to stay and work in the country for up to four years.

They would also be able to bring eligible family members with them.

As of 30 June 2017, there were a total of 90,590 holders of 457 visas in Australia, while 50,420 had been granted permanent residency or a provisional visa following their time on a 457.

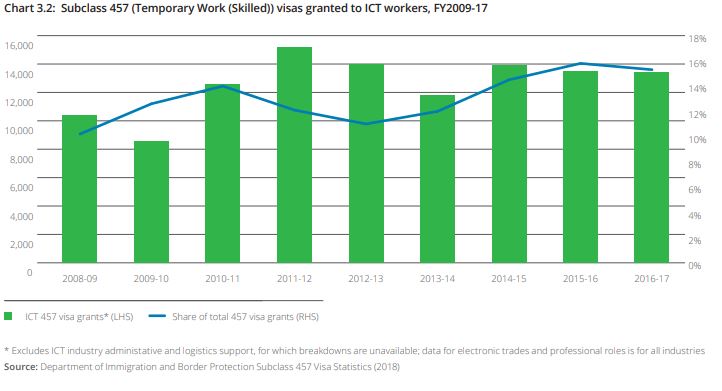

The ICT industry was a very notable employer of such workers, employing between 10 and 17% of all workers on 457 visas.

ACS Australia’s Digital Pulse 2018 shows that number of 457 visas granted to ICT workers has fluctuated between 8,000 and 15,000 per year over the past nine years.

In 2016-17, around 2% of Australia’s total ICT workforce were holding 457 visas.

Changes to "put Australians first"

But the 457 visa came to a halt in April 2017 when it was abolished by the Coalition Government.

Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton, alongside his then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, promised that the decision was “putting Australian workers first.”

The 457 visa was replaced with the Temporary Skill Shortage (TSS) Visa, which was implemented in March this year.

The new scheme is comprised of a two-year Short-Term and a four-year Medium-Term stream.

Some of the key points of difference between the 457 and TSS visas are:

- Two years’ relevant work experience.

- Tighter English proficiency testing.

- A criminal check.

- Mandatory domestic labour market testing.

- Extending the permanent residency pathway from two years to three years.

Since the announcement in April last year the government has made small tweaks to TSS visa regulation, including extending the required timeframe of domestic labour market testing advertisements and allowing LinkedIn job adverts to count as evidence of labour market testing.

These changes also resulted in 216 jobs being scrapped from Australia’s strategic occupation list.

From an ICT standpoint only three jobs (web developer, support technicians and support and test engineers) were cut from this list, meaning most employers are still able to source overseas talent where needed.

However, some of the more stringent safeguards implemented as part of TSS visa reforms could slow down the recruitment process for Australian companies looking to fill skills gaps fast.

With a predicted 200,000 workers required over the next five years to place Australia as a global tech leader the question of whether or not Australia should relax its stance on skilled migration lingers.

The Global Talent Scheme

One of Australia’s most successful technology companies, Atlassian, has been a vocal advocate for relaxing skilled migration reforms in Australia.

“Lack of access to experienced, global talent is the single biggest factor constraining the growth of the technology industry in Australia,” company CEO Mike Cannon-Brookes told a Senate committee hearing in March.

Peter Dutton and co may have been listening to Cannon-Brookes’ remarks.

Shortly after the Senate Committee Hearing the government announced its tech-specific Global Talent Scheme (GTS).

The GTS is a niche 12-month pilot running from 1 July 2018. It is run under the TSS visa program.

The initiative allows both established businesses and start-ups in the tech sector to bring in experienced talent from overseas on a four-year TSS visa.

Tudge and former Minister for Jobs and Innovation Michaelia Cash said about the new scheme: “the government recognises there is fierce competition globally for high-tech skills and talent, and that attracting these people helps to transfer skills to Australian workers and grow Australian-based businesses.”

It is still unclear just how many ICT workers will be granted entry to Australia under the GTS.

Coalition intake policy

Australia’s total migrant intake has been capped at 190,000 since 2012.

Despite this being the case, last year the actual intake only hit 163,000 – 20,000 less than the previous year and the lowest annual intake since 2007.

These figures are perhaps an early indication of the impact the TSS visa and its stricter vetting requirements will have on net migration levels to Australia.

There have also been reports that Dutton attempted to lower the cap from 190,000 to 170,000 last year.

Malcolm Turnbull categorically denied such reports, vowing “it is completely untrue, it is completely untrue, it is completely untrue.”

And while Dutton never confirmed the suggestions, he has publicly stated that he is not “tied to” the current cap and has looked at “different options.”

He has also stated that he believes the economic impact of lowering migration “is a positive one.”

Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott has been less cryptic with his views on the matter, affirming he wants the cap lowered to 110,000.

So, with the likes of Dutton, Tudge, Turnbull and even Cash all playing a hand in Australia’s skilled migration policies over the past 18 months, the question now is: what will David Coleman make of the role ahead of the next election?

Labor's response

Although Coleman has yet to give any proper indication on how he will approach his new role, he has already come under fire from the opposition.

“The minister responsible for one of the most complex areas of policy – including Australia’s permanent migration intake, our humanitarian program, and temporary work visas – won’t have a voice in Cabinet,” said Shadow Minister for Immigration Shayne Neumann.

With the latest Newspoll showing Labor sits at 56% on a two-party preferred basis and a Federal Election looming, Neumann may soon be able to implement Labor’s policy on skilled migration.

What would this look like?

The ALP’s 2018 National Platform Consultation Draft suggests that Labor’s skilled migration policy will be shaped around economic and societal demands.

“Labor is committed to a range of polices to lift workforce participation and the qualification level of the workforce in response to an ageing population and the demand for higher levels of skill and mobility,” it says.

Similar to the coalition, Australian workers will be prioritised when employers look to fill skilled vacancies.

It also states that specific skills shortages will be complemented by domestic training policies.

Neumann has shared his concern over the 457 visa cuts and its impact on the Australian start-up sector and national innovation.

“Skills shortage issues have plagued our digital economy for years without recognition or action by the Liberals, and last year’s sudden skilled migration changes sent shockwaves of uncertainty through the business, innovation, and education sectors,” he said.

He has proposed a new four-year SMART Visa that would be targeted at global educators, innovators and researchers.

He also pledged his intend to establish an Australian Skills Authority that would work in conjunction with industry, unions, education providers and state and local government to project Australia’s future skills shortages and provide specific training accordingly.

So what will happen next?

We may still have to wait until the next election to find out.