I went from writing my first line of code to a $US226K job offer in just 8 months.

I got offers from Google, Lyft, Yelp, cloud unicorn Rubrik, IBM Artificial Intelligence, and JP Morgan Chase.

This is my story and it may help you in your own job search. I hope it inspires current software engineering job seekers – especially from non-traditional backgrounds.

You may be thinking, “How likely is it that I could pull this off too?”

In this article, I'll be specific about my decisions and thought processes. I'll also give you some links for further reading.

First, I must acknowledge that I have benefited from significant privilege: I am a white, straight, cis, male with a bachelor’s degree from a top 20 US university. I had also built up a network after three years of working in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Every job seeker's story will be different, but I hope yours benefits from mine.

Deciding to take the plunge

On July 29th, 2018, I made an irrational decision.

I was choosing between a Chief of Staff role for a hyper-growth adtech company and attending a coding “bootcamp.” The Chief of Staff role was lucrative and certain - seemingly an extraordinary ticket to a Silicon Valley fast track. The bootcamp seemed expensive and risky.

I had written my first line of JavaScript five weeks earlier on June 24th with no intention of becoming an engineer. I already had a degree in Economics and three years’ experience as a non-technical management consultant for non-profits. I just wanted to make myself a more attractive candidate for roles that involved working with engineers in the Bay Area.

Actually becoming an engineer seemed like a moonshot idea. I had heard stories of people self-teaching and using bootcamps to do so in under a year. But I struggled to believe that I could do the same.

Most engineers I knew had four-year computer science degrees, years of experience, and seemed to speak a foreign language. How could I learn all that in so little time? Plus, doing so would require I throw out my career-to-date in operations and strategy — a high cost for an uncertain reward.

The Chief of Staff role, on the other hand, looked like a dream come true. I would be the most junior member by ~10 years in “the room where it happens” as the company navigated upcoming acquisition talks. Salary negotiations went better than expected, and it seemed I would likely inherit a department of my own after a few years.

But once I started coding I didn’t want to stop. I loved the technical challenge, was thrilled to make headway against something so intimidating. And I figured developing a second professional skillset might prepare me for an unusually impactful career.

An inner voice also asked if becoming an engineer would be as personally transformational as professional: If I succeed in learning this, what couldn’t I learn? This attitude, more than anything else, would become the theme of my journey.

I took an online course and, after coding ~40 hours/week for three weeks, I decided to apply to Hack Reactor, which I had heard described as “the Harvard of bootcamps,” just to see if I could get in. I passed the entrance exam by the skin of my teeth the same week I received the Chief of Staff offer.

After 72 hours of soul searching I checked my bank account one last time. I estimated I would have three months’ rent and food after Hack Reactor. Just enough time to find a job, I thought.

I chose bootcamp.

I declined by phone with the adtech company, hung up, and was hit by a wave of mixed emotions. Part of me was scared: I’m throwing away a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for a moonshot idea! Another part excited: The only thing that stands between me and regret is taking risks!

Soon my excitement won out. No turning back now – I was in for an adventure.

Learning to code

“You don't have to be great to start, but you have to start to be great.” – Zig Ziglar

Hack Reactor and other “bootcamps” aspire to do in three months much of what traditional university CS programs do in four years: prepare students to compete for top-tier software engineering jobs.

The goal is ambitious, and every moment counts. For 12-14 hours/day, 6 days/week over the course of 3 months, the program threw us repeatedly into overwhelming tasks against tight time constraints.

At the start of every assignment I would get a sickening pit in my stomach and think, This deadline seems impossible – I don’t even know where to start! But somehow I would (almost) always hack together a working solution just as time expired.

After enough reps, I started to associate the pit in my stomach with a sense of excitement — the more impossible the challenge seemed, the more satisfying it would be to find a solution.

Hack Reactor wasn’t just teaching content, it was teaching a new kind of grit and growth mindset, and the process was exhilarating.

Still doubting I would get a job before my savings ran out, I invested in the best learning and self-care habits I could find.

To ensure ample sleep for learning, I kept strict bedtimes.

To fight repetitive stress aches, boost wellbeing, and support learning, I worked out every other day.

To improve retention and make each day’s learning a little better than the last, I reviewed core lessons and reflected on what went well and what did not most evenings.

And most importantly, to maintain baseline wellbeing during such an intense schedule, I meditated for a full hour every morning before class, usually using a mix of vipassana (a form of body scanning) and loving-kindness techniques.

This last habit may strike some as extreme, but the evidence behind meditationimproving wellbeing is strong, especially loving-kindness. I cannot overstate how valuable this practice was in helping me embrace the curiosity and joy of learning rather than grow anxious about the challenges of bootcamp and uncertain employment.

I also benefited from a blessing in disguise. A travel conflict prevented me from enrolling in the in-person immersive, so despite living a 10-minute walk from the SF campus, I had to take the remote program. Between the lack of commute, easy access to food, and the quiet of my apartment, I was able to protect another ~90 minutes a day of uninterrupted deep work.

The first six weeks involved two-day pair programming sprints building on semi-completed code repositories. We raced through rewriting the JavaScript Underscorelibrary, building basic data structures from scratch, learning object-oriented vs. functional programming, calculating time and space complexity, and wiring up a full stack app from client to server to database. Our smaller, 24-person cohort grew close joking with one another over video conference 10+ hours/day.

Three weeks in, I was afraid I wasn’t going to pass the gating mid-course assessment, so I wrote a letter to myself dated in the future explaining how it came to be that I passed the assessment.

I mentioned all my existing self-care and learning habits and added a few more, including reviewing code I didn’t fully understand until I could mentally explain the core concepts to an imaginary 8 year-old (the Feynman Technique).

Three weeks later, I built my first full stack application from scratch in under 24 hours and passed the exam with flying colors. College was a great education. This was another level.

The second six weeks involved more free-form group projects. Taking inspiration from positive deviance, I tracked down and got in touch with bootcamp alumni who were especially successful in the job search. I followed their guidance to set tight personal deadlines for intimidating technical challenges, select “hot” skills on the job market (like working with Docker and microservices), and diversifying my roles across different projects. I arranged a tutoring session with one alum and successfully implemented a feature that originally took him weeks in two days.

Hack Reactor hires some of its graduates from each cohort to serve as temporary, part-time teaching assistants to support full-time staff. After graduation, I took a 6-week position working ~35 hours/week and helped roll out new curriculum, conducted independent research, lectured job-seeking alumni on my findings, and interviewed incoming Hack Reactor candidates.

I negotiated a 6-week position as opposed to the typical 12-week position to give me exposure to the new curriculum while limiting the delay in job searching and studying full-time. I was grateful to learn on the job (teaching in particular boosted my own learning) and the modest pay bought me two more months of living expenses – a big relief!

Securing a job as a Software Engineer

Companies that made me offers:

On December 7, 165 days after my first line of code, my employment with Hack Reactor ended, leaving me with savings to pay for four months’ rent and food. Hack Reactor warns its graduates to budget six months for job searching. The clock was ticking!

I wrote down my goals. I was ambitious and the odds were stacked against me. I wanted:

· A top 25th-percentile Hack Reactor outcome in compensation, hoping for over $120K/annual salary

· The steepest possible learning curve; ideally in a role with both autonomy and access to experienced mentors

· A team and company culture that was technically strong but people-first

· Interesting and meaningful work

· A back-end role, or at least full stack, which were less common than front end roles landed by bootcamp grads

I never imagined I would get everything I wanted and more. But the search would be a rollercoaster of ups and downs.

Hack Reactor left me with a terrific foundation in little time, but I was still weeks, if not months, of full-time study away from where I needed to be to interview successfully at top companies.

I would also have to face relentless, ongoing rejection with no certainty of success. Hiring from coding bootcamps is not yet mainstream, and despite evidence suggesting bootcamps grads perform just as well as those with four-year CS degrees in interviews, it would be an uphill battle to land interviews. And the vastness of topics covered in software engineering interviews meant I could never be completely prepared.

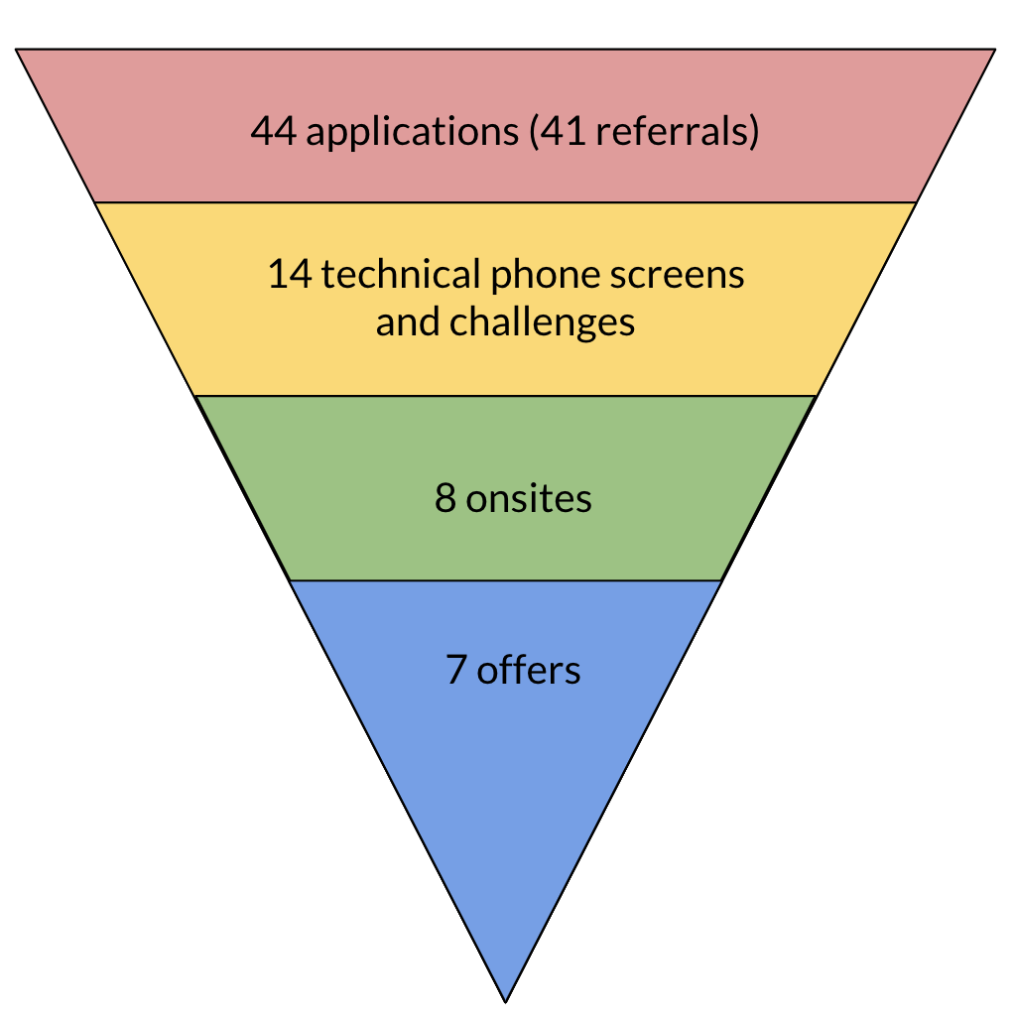

When it was all over, I had applied to 44 companies with 41 referrals and received 14 coding challenges or technical phone interviews, which converted to 8 on-sites and 7 offers by February 15, 2019 - 245 days after my first line of code.

16% of my applications converted to offers just over 8 months after my first line of code

Beginning the search and learning from failure

"Learning is not attained by chance, it must be sought for with ardor and attended to with diligence." ―Abigail Adams

My first weeks of job searching were the toughest. I landed only a handful of coding challenges and an interview with IBM Artificial Intelligence throughout all of December.

Feedback on my first two take-home coding challenges was not encouraging. I went way over time, and was told my code was “neither accurate nor performant.”

My third coding challenge was a multi-hour, heart-thumping affair in which I passed all tests with seconds to spare but failed to click submit before time expired!

I told myself it was a numbers game, and every morning after my hour of loving-kindness meditation, I’d take a minute to remind myself of two things:

· First, while my goals gave me direction, overly focusing on goals would only leave me dissatisfied with the gap between where I was and where I wanted to be. I wanted habits over goals.

· Second, I reflected that regardless of what job landed, the real prize of this journey was personal, not professional, transformation. I was lucky to have months dedicated full-time to learning how to learn, and I was falling in love with it!

I knew early failures could be seeds for later success, but they would require special care. I made sure to do a post-mortem on every failed coding challenge and interview, then redo the problem in my text editor until I solved it. One 20-minute prompt took me 9 hours over three days to solve!

I kept notes on new concepts and “aha” moments after I solved a problem, treating them as my invaluable collection of “mental models” I hoped would grow sufficient to pattern match to any interview prompt. I would review them on spaced repetition intervals to most efficiently commit to long-term memory.

For problems involving new code syntax, I’d redo them under time pressure to ensure accurate recall in an interview setting.

These habits did more than enhance retention — they built reassuring confidence. I didn’t know if I’d land a job before money ran out, but it was satisfying that even my greatest disappointments were making me better.

I settled into a steady routine, ~8 hours a day, 5+ days/week: study and/or interview, diagnose failure/success, reflect, repeat.

I curated and constantly revised my study plans by first getting a sense for what strong performance looked like in each of the different types of interviews I might encounter (data structure/algorithms, front end DOM manipulation, systems design, etc.). Then I’d estimate the probability of encountering each type in upcoming interviews and weigh that against my self-assessment of my performance to decide what to study next.

Wanting to ensure I only used the best resources, I kept lists of peer-recommended resources organised by topic. When it was time to study that topic, I’d supplement the list with anything new from a quick Google search and then skim each resource to determine the best one or two before diving deep into those. I’d do most prioritisation the day before so I could go straight from my morning meditation into 2-3 hours of uninterrupted deep work the next day.

I spent another 2-3 hours/day building a pipeline of attractive companies, generating referrals, and submitting applications. It took more time than I liked to complete a single application and I had a limited number of top picks, so I did my best to increase app-to-interview conversation rates by

· emphasising results over context or action in my resume

· studying which of my approaches and messages generated referrals fastest via email and LinkedIn

· tracking my entire pipeline in a spreadsheet, and

· following up on all communications.

I treated most applications as experiments in improving return for time invested. Habits paid off here too — steadily putting companies in my pipeline meant that I could immediately look ahead to the next opportunity when I received a rejection.

I also did my best to time applications so I could interview first with less desirable companies while pushing along slower moving processes (like Google’s).

My interview with IBM proved to be a bright spot to my rocky start, but even still, it doubled as a lesson to persist amidst uncertainty. It consisted of a phone interview and three more interviews at the “on-site.”

At the start of every interview I experienced that now-familiar pit in my stomach and thought: I do not know how to do this.

I responded each time by taking a breath and reminding myself: It’s fun turning this feeling into a working solution at home, so imagine how much more fun it will be here where the stakes are higher and the job is on the line!

After the first two interviews, I wondered if my excitement and learning orientation were contagious — my interviewers certainly knew I didn’t see an answer right away, but they seemed to enjoy how the energy in the conversation rose as I neared a solution.

I left IBM encouraged that, while I may not always crack an interview prompt, I could always enjoy sharing a growth mindset under pressure. I’m sure this mentality helped me convert seven of eight on-sites.

Fortunately, seeds sown in December’s failures bloomed into January's success.

Building momentum and early success

"Your hardest times often lead to the greatest moments of your life. Keep going." ―Roy T. Bennet

The first week of January, IBM called with an informal offer with formal details forthcoming. Could I use this as leverage in the meantime? I thought. I shared the news with a Google recruiter, who responded by accelerating me past the phone interview straight to an on-site.

Suddenly, I could command recruiters’ attention. I immediately informed all companies I was speaking with that I had an offer. Doing so during the start of the new year immediately heated up my pipeline.

The next week, I felt confident for the first time in all four technical interviews at a JP Morgan Chase on-site, finishing most of them with time to spare. I was overjoyed my work in December had so clearly paid off.

My Google on-site was a few days later. The difference in difficulty was shocking. I performed terribly in my second interview involving asynchronous JavaScript promises.

I took a moment in the restroom at the lunch break to regroup with a micro-meditation. I figured I had almost no shot at a job offer, so the objective was now to learn as much as possible from my failure.

I knew I’d do a post-mortem in the evening. In the meantime, I challenged myself to see how much gratitude and equanimity I could cultivate in such a high-stakes environment. After all, how exciting was it I was interviewing at Google?

The idea seemed to help me pull out of my tail-spin and I got better throughout the afternoon. By the time I left, I even had a glimmer of hope Google might still offer me a job.

Per my post-mortem habit, I went home and found online resources to help me build a JavaScript promise from scratch. The next day I took three phone screens and the ups-and-downs struck again.

I performed strongly on a call with a security start-up. I Embarrassed myself with a small energy start-up. And I had the comeback of a lifetime on the phone with Rubrik, a cloud storage unicorn.

Rubrik asked another question on promises, harder than the one from the Google interview I had failed a day before. Having done my post-mortem, I innovated on the spot and raced to the finish just as time ran out.

The interviewer said I may have been the first bootcamp grad the company had ever interviewed — they traditionally hire only from prestigious universities — and he couldn’t believe I wrote my first line of code the summer before. I did a little dance in my room.

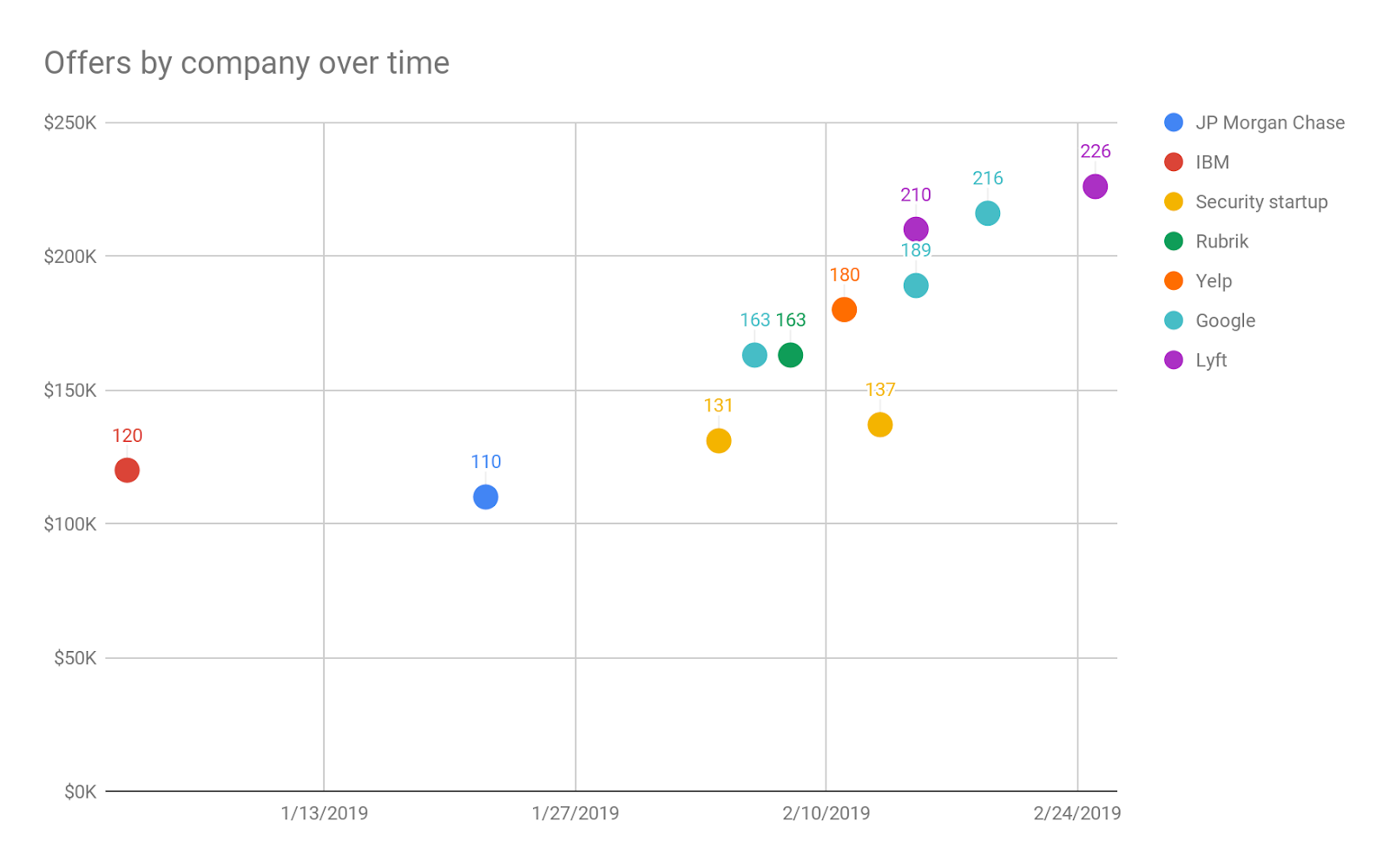

The next week, JP Morgan Chase called and offered me $110K/year, with no equity or bonus. I didn’t think it was a cultural fit, and I wasn’t yet at my $120K/year target, but I was thrilled to have my first official offer. Someone was going to pay me to code!

I started to handle several calls per day from phone interviewers, recruiters, and advisors, and the often unpredictable ups-and-downs continued. Google called and said on-site results were mixed but I’d be moving to Hiring Committee. Uber offered an on-site. I thought I performed strongly on an Amazon phone screen but didn’t get an on-site. And I thought I blew a Yelp phone screen and got an on-site.

As on-sites came and went, I had to watch my words around recruiters. The security start-up said they were afraid they wouldn’t be able to keep up with big companies like IBM and JP Morgan Chase and asked what salary offers I had received.

I almost bit the bait, but paused and deflected the salary question as Hack Reactor instructs. “I’d actually like to go the other way – can you tell me your range and I’ll tell you if you’re in the ballpark?” I said. “Sure, we start at $125K.”

$125K. That exceeded my goal!

I looked away hoping to disguise my excitement by making it look like I was thinking about it. I turned back and said calmly, “If that’s your starting point, I think we can have a conversation.” He responded: “Oh good, I’m relieved we’re still in the running!” Me too, I thought.

The formal offer was in a few days later: $125K plus $6K/annual in stock options at current valuation. But the money was almost insignificant! It was a good cultural fit, a fascinating back end role, and mentorship opportunities looked unusually strong. The team of ~40 engineers all had at least two years’ experience and were mostly from top schools like MIT, Stanford, or Berkeley. It was everything I wanted!

But the offers were just getting started.

Negotiating across offers and selecting a company

"Effective negotiators look past their counterparts’ stated positions and delve into their underlying motivations... they are relentlessly curious." –Chris Voss

Rubrik called two days later and shocked me. They wanted me to be their first-ever bootcamp hire too. Rubrik was already valued at $3.3B — a hot new unicorn and coveted place to work by software engineers with plenty of experience. I laughed with the recruiter, overjoyed such a competitive company wanted me, and hung up so excited I almost didn’t realise I had a missed call from Google.

I dialled back with bated breath. The recruiter got right to it: “I just got out of Hiring Committee and wanted to call you right away. We’d like to make you an offer — ”

I couldn’t contain myself. I yelled, jumping into my empty kitchen. Google! The gold standard of software engineering and my hardest interviewer had decided they wanted me! Then she mentioned numbers and things got surreal. $163K all-in: $120 base salary, $18K minimum bonus, and $25K annual in (liquid) equity.

$163K.

Are you out of your mind? I thought. My last tax return declared $77K. That is a stupid amount of money.

I took the afternoon off and walked around my neighborhood dancing when I thought nobody was looking and calling family members to share the unbelievable news.

The next morning, I was back to the grind, studying negotiation instead of algorithms. Overnight, the recruiters that had shepherded me through interviews became my counterparts in negotiations. I felt like a lone sheep amidst a pack of wolves – these were professionals and numbers could swing tens of thousands of dollars in conversations that lasted minutes.

Initially I feared coming across as greedy, but my Hack Reactor career coach was adamant. She said it was expected, and money aside, it demonstrates thoughtfulness, confidence in difficult conversations, and sets expectations for the first weeks on the job.

I saw almost a 90% increase in compensation by waiting and passing on my first offer

The next few days flew by in a flurry of phone calls with recruiters and advisors, studying, preparing, and conducting post-mortems on negotiations. I wrote one-pagers anticipating every negotiation and conducted post-mortems on what went well and what did not, similar to how I reflected on failed interviews.

I learned to love it. Each conversation was a fascinating puzzle, with layers ranging from high-level strategy, like when and how I shared information, to moment-to-moment tactics, like my tone of voice. It was especially fun to have so many at-bats – I would sometimes talk to multiple recruiters in a single day, each phone call doubling as another opportunity to try out new skills and learn from mistakes.

I had read Harvard Negotiation Project’s Getting to the Yes and Getting Past the No in college and was familiar with concepts like BATNA and win-win solutions. But I took most of my inspiration from Chris Voss’s Never Split the Difference, which I re-read immediately after Google’s offer.

I also scoured blog posts by Haseeb Qureshi, another earn-to-give bootcamp graduate, and chatted regularly with my Hack Reactor career coach who had advised hundreds of negotiations before mine.

Rubrik’s first offer came in at $163K, matching Google perfectly. Then Yelp called with the latest plot twist. They “levelled-up” my application to a non-entry level role and offered me $160K plus a $20K sign-on bonus for $180K all-in first-year compensation.

$180K and a non-entry level role?

I put on my very best performance at my Yelp interview — finishing every challenge with time to spare, adapting code seamlessly to meet new constraints, and making remarks about systems architecture using back-of-the-envelope calculations that seemed to surprise my interviewer. But that didn’t change the fact I had zero experience! Google and Rubrik immediately said they’d prepare a counter offer.

Finally the job search climaxed.

Lyft emailed asking to get on the phone. Lyft was by far my favourite interview experience, but I didn’t believe my on-site performance merited an offer. I conceptually solved one interview almost immediately, but never got my code to work. I pulled off a late comeback in another but failed to submit as time expired. Stretched thin across multiple rounds of daily negotiations, I responded with this exact email:

“I’m juggling a handful of different calls right now. Do you mind breaking the news by email? I’m guessing it’s a rejection, in which case I would love to get 1-2 sentences of feedback from each interview. Other than that, thank you for your time and shepherding me through the process!”

She responded with one line: “It’s not a rejection :)”

What! Would no company reject me? I couldn’t believe my top choice was back on the table. We talked numbers the next day: $210K all-in.

$210K.

And to think that was Lyft, where I would have loved to work, money aside! A couple of my friends at Lyft were some of my favourite people — harder to say if they were kinder than they were brilliant or vice versa — and my interviewers seemed cut from the same cloth.

I informed everyone a last-minute offer had been made and set a decision deadline for one week, encouraging everyone to make their final offers. I was getting worn down in constant negotiations, I felt a deadline would professionally bound the time everyone was investing in my candidacy, and Voss suggests deadlines can be used to your advantage.

Google had prepared $189K to come in over Yelp, but said it would come back again given news about Lyft. Rubrik agreed to get on the phone. Yelp and the security start-up said they couldn’t negotiate further, and I was no longer keeping JP Morgan Chase or IBM up to speed. Uber, my only other onsite, did not make me an offer.

The Lyft team had me for lunch and I swooned. Teams at Google, Yelp, and the security start-up were enjoyable, but 9 people took time out of their day to lunch with me at Lyft, laughing as if I were already part of the team. They wanted to staff me on the company’s number one 2019 priority and a senior engineer told me he would happily serve as a mentor. Lyft was also months away from an IPO.

I had it all: mentorship, opportunity in a high-growth environment, a people-first culture, exciting work, and now outrageously high compensation.

Rubrik didn’t counter offer in time, but Google came in at $233K, $216K before their 401(k) match and charity match programs (which I consider good as cash since I earn-to-give and will be donating 25% of my pre-tax income this year). The team was also a good cultural fit, and Google is world-class in developing junior engineers into top talent.

I grappled with the decision for days, wavering between Google and Lyft, but gradually growing confident that, compensation aside, Lyft was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up. I negotiated a final package of $226 all-in compensation: $135K base salary, $71K in equity at pre-IPO valuation, and $20K sign-on bonus. On Monday, February 25, 245 days after my first line of code, I spoke the two words that brought it all to a close: “I accept.”

Six months later, I couldn’t be happier working at Lyft. And to my delight, my morning reflection was dead on. My team is supportive, my work fascinating, and my compensation strong, but the priceless reward of becoming an engineer was falling in love with learning. Now that I’m in love, I don’t intend to leave it.

In search of software engineering roles?

I've curated the list of top resources I used to prep for interviews. I'm also offering coaching sessions to job seekers that commit 10% or more of their future income to high impact charities. Get access to both here.

Note: I write with a pen name to maintain a little separation between my personal life and growing presence as a job search coach.

I shared specific compensation information in this article for two reasons. One, I want this post to be as useful as possible to job seekers from non-traditional backgrounds, many of whom may be less familiar with these numbers. And two, because sharing our salaries is a concrete way to fight pay inequality that hurts everyone, especially minorities.

Fighting pay inequality is also aligned with the mission and culture of Lyft, which is extraordinarily committed to fighting pay inequality. It administers a third-party pay equity audit every year, and this past year Lyft became a different kind of “unicorn” in Silicon Valley after no systemic pay gap was found. Precise salary information already exists on sites like paysa, levels, and blind, so details shared here are nothing new.

Finally, I'm grateful for the support of many on this journey, especially Lena Johnson, my job search coach and negotiation advisor, and Robin Kim, my technical mentor. Thank you!

This article was first published on freecodecamp.org and is republished on Information Age with permission. It has been edited for clarity. Note all dollar amounts are in US dollars.

FreeCodeCamp is an organisation that helps people learn to code for free.

.jpg)