When I was offered the chance to try out Cisco’s Webex Hologram this week, I jumped at the opportunity because I see the mass adoption of augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR) – sometimes collectively referred to as 'mixed reality' – as the next major milestone in how we interact with the digital world.

Cisco's Hologram is a 3D video conferencing tool that lets participants appear as though they are sharing the same physical space without using cartoon avatars like those of Meta's full-VR Horizons Workrooms.

I tried out the Hologram in Cisco's North Sydney demo showroom, where alongside a mix of screens, an innocuous mannequin head donning a Microsoft Hololens 2 sat on a plain white desk facing a black wall.

After sitting down at the desk and pulling the headset on over my glasses, I joined a call with a man wearing a Hololens of his own. He appeared to be sitting across from me, hands calmly resting on his desk for another in a line of Hologram demonstrations, but in reality he was in a room at Cisco HQ in San Jose, California.

To him, I was a disembodied, featureless mannequin head with hands that were tracked as I moved them in front of the Hololens’s camera.

He took out a book with the title TCP/IP and placed it on the table with its spine facing me.

“I’m going to show you parallax,” he said.

“Move your head around. Can you see the front and the back of the book?”

This was meant to be one of the big ‘ah ha’ moments of Cisco’s Hologram demonstration: a 3D video call.

But it didn’t work.

The whole of the video call’s floating square panel moved with my head, staying perfectly flat. The yellow book's front cover remained elusive.

We tried a few re-calibration sequences. I held my palm up to my face to bring up a menu with buttons for me to press, index finger poking out into the empty space in front of me.

Alas, it was clunky. The Hololens struggled to accurately track my hands and the buttons stayed forever out of reach.

Eventually, after some trial and error I successfully restarted the device, took off my glasses, tightened the headset back over my skull, and could see the parallax feature.

It was impressive knowing that, by moving my head around, I could see different angles of a real object from 12,000km away.

The other caller held up a glass of water and again I could move my head around and see it, noting how his reflection inverted in the grainy water footage.

Cisco achieves this 3D-like effect through a bank of 19 cameras in front of which my US counterpart patiently sat.

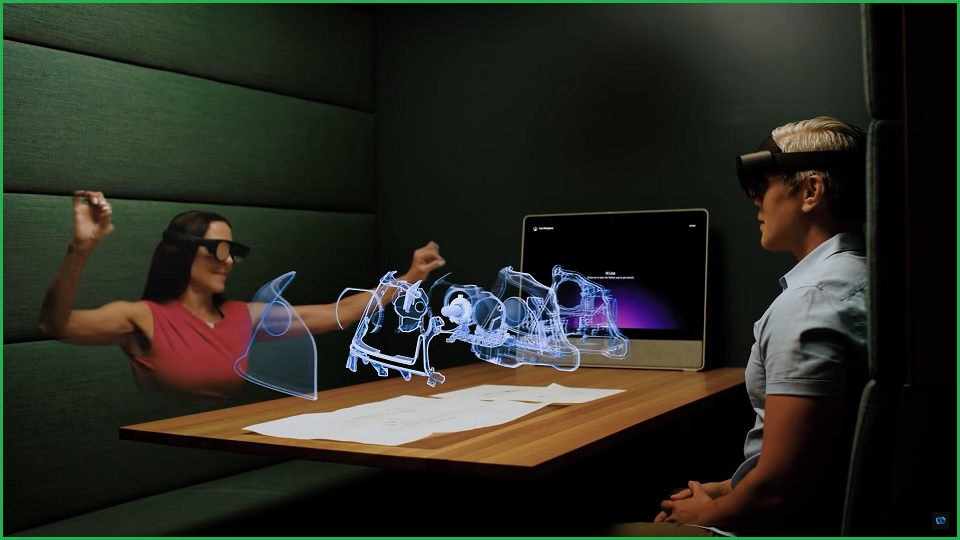

After briefly marveling at the wonders of a 3D video call – the demo was running out of time – I was handed, from across the desk, a digital car which we could each hold and manipulate, pinching and squeezing to move and re-size as you would on a touch screen.

The idea is that Hologram lets you collaborate with digital objects in the same space, so to speak, across vast distances.

Again, the imperfect hand-tracking stood in the way.

Stick to Zoom for now

I sat there futilely opening and closing my hands to grab this toy car unsure exactly how this this feature – or any of the early-stage Hologram product – would be much better than joining a standard video call with a screen and a mouse or touchpad.

Unfortunately, the fidelity with AR isn’t quite there yet to make the immersion, in the context of a video call, worth the hassle. Images tended to look washed-out and low-res, even in Cisco’s darkened demo room.

Mostly, though, Cisco’s attempt to make the person on the other end feel more ‘there’ by adding spatial dimensions has other consequences that end up making the call less personal.

Because current AR tech still covers up the wearer’s eyes, you end up seeing less of their face than you would on a standard video call.

AR hand-tracking still has some way to go.

Similarly, the way we currently make video calls, through smartphones, laptops, cameras on monitors or embedded in walls, lets you into each other’s space.

You can call someone and walk around your home, for example, and lay your laptop down on the kitchen counter as you make a cup of coffee.

Not so for a Hologram caller who, in order to slightly project themselves as a 3D video, sits alone in front of a bank of cameras, staring back at a disembodied head and the vague flapping of poorly tracked hands.

Even though the current iteration leaves a lot to be desired, the concept of a Hologram conference call is alluring especially in a boardroom context where people dialing in have their faces blown up on a widescreen panel.

If meeting participants can instead appear to be sitting around the table together, their image recorded and projected from a row of cameras in another office, that would change how we view ‘telepresence’.

But it doesn't look like the tech is there just yet.