As if the steady flow of brutality from Ukraine wasn’t enough to test the world’s emotional fortitude, the conflict is also testing the world’s cognitive stamina after Ukrainian TV broadcasted a deepfake video of the country’s president supposedly urging citizens to surrender.

Originally posted on Twitter on 16 March, the video featured a convincing AI-generated facsimile of Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, allegedly calling on Ukrainians to lay down their arms and surrender to the Russian invaders.

“Dear Ukrainians! Dear defenders!”, the fake president said. “Being president [is] not so easy. I have to make difficult decisions… it’s time to look it in the eye.”

The video – which was eventually deleted by Twitter for violating rules against synthetic and manipulated media, also adopted by Facebook and Tik Tok – ran on Channel 24, a major national news network and website that had broadcasted the fake video to millions of Ukrainians before explaining that the video aired while hackers had taken control of its systems.

“We have repeatedly warned about this,” the network posted on Telegram. “Nobody is going to give up, especially in conditions when the army of the Russian Federation suffers defeats in battles with the Ukrainian army!”

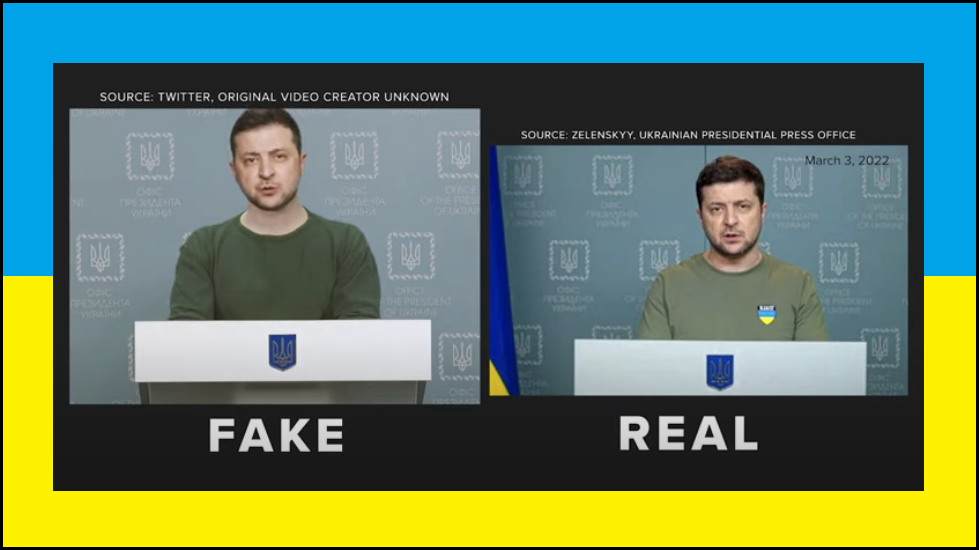

Using applications including the InVID video forensics and TinEye reverse image search tools, fact-checking organisation VERIFY closely examined the video and confirmed that it had been created using deepfake tools and images taken of the president at press conferences on 24 February and 3 March.

Side-by-side examination of the two videos highlights clear differences: the fake Zelenskyy, for example, is taller, has broader shoulders, and has a different facial structure.

Another recent deepfake showed Vladimir Putin claiming that Russia had reached a peace deal with Ukraine – which would have been news to the millions of Ukrainian refugees and terrified citizens huddling in basements as bombs rain down around them.

Often with little more than a smartphone to watch the war, such citizens depend on the integrity of news and wouldn’t have the time or emotional space to critically analyse the videos – or to note the Ukrainian National Guard Twitter post, or the response in which the real Zelenskyy called the deepfake a “children’s provocation”.

The front line of information warfare

Although its author is still unknown, the detection of the Zelenskyy deepfake – and the implication that many other manipulations may be going unnoticed – highlights the degree to which information warfare has become critical to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Nation-state security specialists observed a large uptick in Russian intelligence gathering and research into forensic-security countermeasures during 2021, Cristin Goodwin, assistant general counsel for cybersecurity and digital trust with Microsoft, said before the war in a webinar noting a “real concentrated effort, predominantly from Russia, to pursue interests in the Ukraine…. From a nation-state attack perspective, Russia had a big year.”

“Nation states are pursuing intelligence,” she said, “and think tanks are advising governments to advance the state of thinking and change the way that government policies may be reflected.”

“We should all be concerned about Russia’s willingness to abuse supply chain and trusted technology relationships, because those are essential to the interconnectedness of the Internet.”

Deepfakes are just one of many threats to that interconnectedness, given that they have become worryingly easy to generate thanks to both rapid improvement in the technology and an explosion of source material that gives malicious actors plenty to work with.

The technology has driven an epidemic of deepfake scams and robberies, highlighting why AI is now suffering major trust issues.

A recent Accenture report found that just 22 per cent of Australian consumers trust the way organisations are implementing AI – far lower than the 35 per cent globally – while Australian executives in the study were universally concerned about the impact of deepfakes or disinformation attacks.

Trusting the emerging ‘metaverse’ will require ways to demonstrate authenticity, Accenture argues – and while experts can detect deepfakes using the right tools, businesses are increasingly considering how to authenticate data and AI with tools like the C2PA anti-deepfake standard.

Yet for every countermeasure, Goodwin said, determined threat actors are dreaming up workarounds.

Studying the ways forensics teams spot nation-sate campaigns, she said, is “a really deliberate tactic that shows the level of refinement coming from these actors. If they understand how those in the threat intelligence space spot Russian activity, they can hide their behaviour more intentionally.”